Who Defines “Professionalism” Asks Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellow Gary Enrique Bradley Lopez

This past year, UnidosUS launched its first-ever Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship. The program is geared to first-generation students pursuing their undergraduate, graduate, or doctoral degrees and recent college graduates who identify as Afro-Latinx and are passionate about racial equity and making meaningful change in their campus community, workplace, and beyond. ProgressReport.co is publishing profiles of the participants throughout the spring and summer.

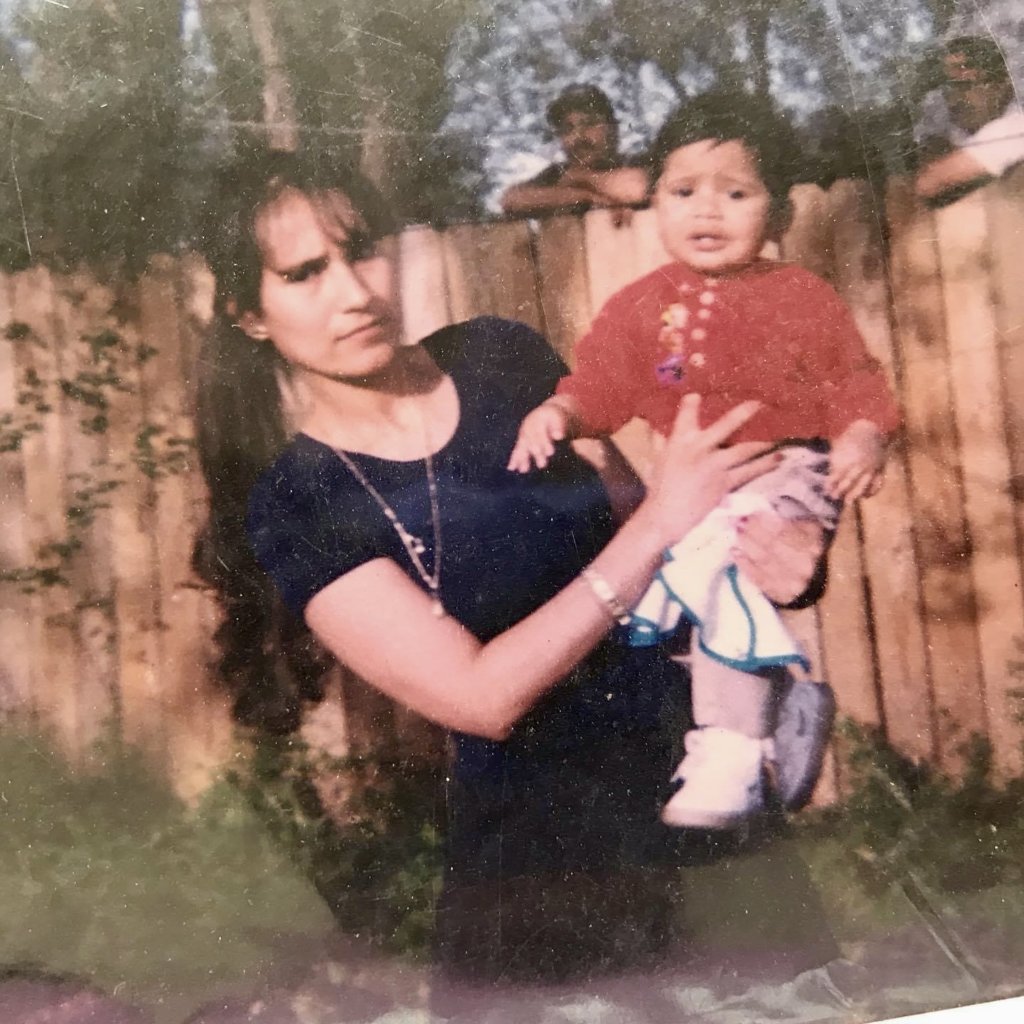

Gary Enrique Bradley-Lopez has a sneaking suspicion that his mother, a Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant, misunderstood the term “special” in a conversation he was helping to translate between his mother and his elementary school administrators when he was just nine. He figures he must have told her they were offering him special classes and that somehow the learning disabilities cue never came up.

To this day, Bradley-Lopez has no idea if he ever had a disability, and he’d hardly be worried if he did, for he’s proven himself to be special. Bradley-Lopez graduated high school just shy of his 18th birthday and immediately enrolled in Kansas City Community College with a full-ride theater arts scholarship. Two years later, he had a bachelor’s in communications and journalism from the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and a year after that, he had a master’s in organizational leadership from Fort Hays University in Kansas. Now 23, he has just finished the first year of a Grand Canyon University doctoral program in educational leadership. He has also taken on a full-time job at the Kansas City Beacon, heading up a new initiative that aims to put diverse researchers into the community to learn what an increasingly multicultural population wants to learn from the news.

“I remember this one teacher telling my parents that if I go to college, there’s a good chance there are great opportunities for someone to take notes for me because I would apparently need a lot of help in college, but I ended up taking notes for other students who needed that,” says Bradley-Lopez, who notes he’s gotten comfortable with confronting uncomfortable cultural norms and stereotypes in just about every aspect of his life.

Harnessing the Best as Well as the Quirkiest Parts of One’s Identity

For example, as with most of the other 11 participants that he’s been getting to know this year through the UnidosUS Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship, Bradley-Lopez never knew which ethnic box he was supposed to fit into.

“A lot of situations were very similar, right? Like struggling to figure out what you are, who you are, if you’re Black enough, if you’re Hispanic enough,” he says.

Born to a Black father and a Mexican immigrant mother, folks in the American Midwest struggled to identify him, so he seized the opportunity to do it for them, referring to himself as Blaxican or Mejinegro.

Then came the questions about Bradley-Lopez’s energetic, upbeat, and playful personality. He was a special ed student in remedial classes, did that have something to do with it? Some teachers and loved ones probably thought so. Take, for example, the time his dad and brother were playing video games while his sister sat and read a book. When Bradley-Lopez came to see what the video game was all about, his father shooed him away, suggesting he go read a book since he needed so much help in school.

“I haven’t ever stopped reading,” says Bradley-Lopez.

And then there was the time a couple of weeks ago that he met up with some high school friends to talk about old times.

“They noted that I was always the goofy, silly one in high school,” he reflects. “But I was also the first one in my high school to graduate college,” he says.

These projections and stereotypes about what smart and successful people should act or be like fueled Bradley-Lopez’s already high level of energy and got him thinking about what social inclusion in work and school can and should look like in practice.

“I just wanted to prove to everyone that I could do it,” he says, noting that sometimes it meant harnessing the misconceptions to then flip them to his advantage.

For example, since Bradley-Lopez was being tracked into community college as a remedial student, he had to maintain a high number of credits, which could only be attained through summer classes. At the same time, he couldn’t afford to float on his scholarship, so he continually picked up jobs in communications or retail to pay expenses and stave off debt.

“I never had a summer break until I went into my doctoral program,” Bradley-Lopez explains.

Even now, he’s so engaged with his studies and his work that he hardly feels he needs time off. Just a few weeks into his job as the community engagement manager for the Kansas City Beacon, he’s thoroughly intrigued by how greater social engagement with the local public can make journalism accountable in terms of both informing and representing that public.

“There’s a lot of underserved populations here, so my job is basically to hire community representatives to investigate, bring the information back to the newsroom, and start educating our journalists on how to be more engaged in those communities,” he says.

Recruiting diverse reporters is a big part of it, and Bradley-Lopez says some of the community engagement specialists he’s hired are already considering a news-related career. At the same time, it’s about sensitizing and instilling a spirit of inclusivity among everyone in the newsroom, regardless of their background.

As this new system of reporting takes shape, Bradley-Lopez is thinking about what media products would be useful to underrepresented communities. For example, this cash-strapped non-profit newspaper doesn’t have the resources to translate all its stories into Spanish for the area’s growing Latino community, but it can create the infrastructure to publish bilingual content. Bradley-Lopez also feels that a 12-minute daily news podcast in Spanish could also reach deeper into the community. The survey results that his engagement specialists are collecting can help him and the editors figure out just how to package such products.

“It’s all about increasing news accessibility,” Bradley-Lopez says.

What Is Professionalism Anyway?

So how do all of these experiences intersect with his doctoral studies and his participation in the UnidosUS Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando program?

In the Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando advocacy and training module focused on free community college for all low-income students, and he was able to use his own story as proof of what those kinds of tuition breaks can do to propel underserved populations through their education. The process of learning to share publicly about his educational trajectory and identity as Afro-Latinx led to what is now his dissertation topic, and this shift happened during the first online workshop.

Bradley-Lopez noticed other participants talking about code-switching or thinking about how they chose to dress and how they chose to show up in social or professional environments. He found himself so comfortable among his peers that he started talking to them just as he would his own siblings—essentially shedding certain linguistic and tonal behaviors considered standard in American professional circles.

“I know I’m not being professional, but I’m just really excited,” Bradley-Lopez exclaimed to his peers in the Zoom meeting.

UnidosUS education consultant Ser Alida Reyes, a University of Mississippi MFA in fiction candidate who helping to coordinate the Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship, responded with three words on the Zoom chat: “Professionalism is whiteness.”

That was the ticket, that realization that the traditional business mold had been shaped by rigid White, colonial structures. Breaking that mold and pushing against it is how Bradley-Lopez has been able to dive into his doctoral studies, dig deep into concepts of leadership as a post-grad, and steer a newsroom into a greater understanding of cultural representation and human authenticity. It was his fun, theatrical style that earned him his free ride to community college and on to so many other endeavors in higher education and public-facing communications, and it was his willingness to embrace himself that put him in the presence of other Afro-Latinx leaders who are on the same journey.

This past year, he’s been digging around in the literature to see how this concept of professionalism has impacted Black and Brown people. He has found a lot of research on professionalism for women and the Black community, but not as much on Latinx and practically nothing on those identifying as Afro-Latinx. As such, his Afro-Latinx Líderes peers may very well become a part of his field research.

He says all the Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando fellows arrived in typical business attire for the in-person and online Congressional meetings to advocate for their policy memos, but he felt much more confident in how he presented who he was.

“There’s nothing more authentic than telling your story because no one else can tell it like you can. That’s what we learned in the program,” he said. “For me, staying true to my authentic self was being true to my story and being proud of sharing about my community.”

He’s not sure where all of this will lead once he defends his dissertation. Maybe it will be related to his current newsroom job, maybe it will be teaching college. What he does know, as he so authentically stated with a confident grin during a February video interview at the Afro-Latinx Líderes Fellowship conference in Miami, is this:

“Being Latinx is dope.”

-Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS senior web content contributor and the former editor of ProgressReport.co.