UnidosUS and the National Urban League convene education stakeholders to broaden perspectives in California on the future of assessment and accountability.

This spring, during a convening of students, parents, educators and civil rights advocates to discuss the future of K-12 standardized assessment and accountability, Los Angeles Unified School District Board Member Kelly Gomez asked a question that set the stage for the day’s discussions:

“Does the federal accountability system actually lead to positive change at our schools?” Gomez asked. “I don’t know. I think it’s really up in the air.”

Board Member Gomez’s doubtfulness is shared by many. Civil rights groups have historically been supportive of end-of-year tests as a measurable way to inform targeted interventions and hold schools accountable for providing equitable education to all students, regardless of their background. However, in recent years, they’ve come under scrutiny, even among their original proponents, for the way they narrow the curriculum and often end up punishing the lowest-performing schools rather than leading to increased support and resources. The debate has become more pronounced since the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted academic progress and widened already existing achievement gaps for historically underserved students.

The event, Broadening Perspectives in California: Shaping the Future of Assessment and Accountability Convening, was the first of several meetings organized as part of the second phase of The Future of Assessment & Accountability Project (FOAA), an initiative launched in 2022 by civil rights partners UnidosUS and the National Urban League to reimagine how best to measure student learning.

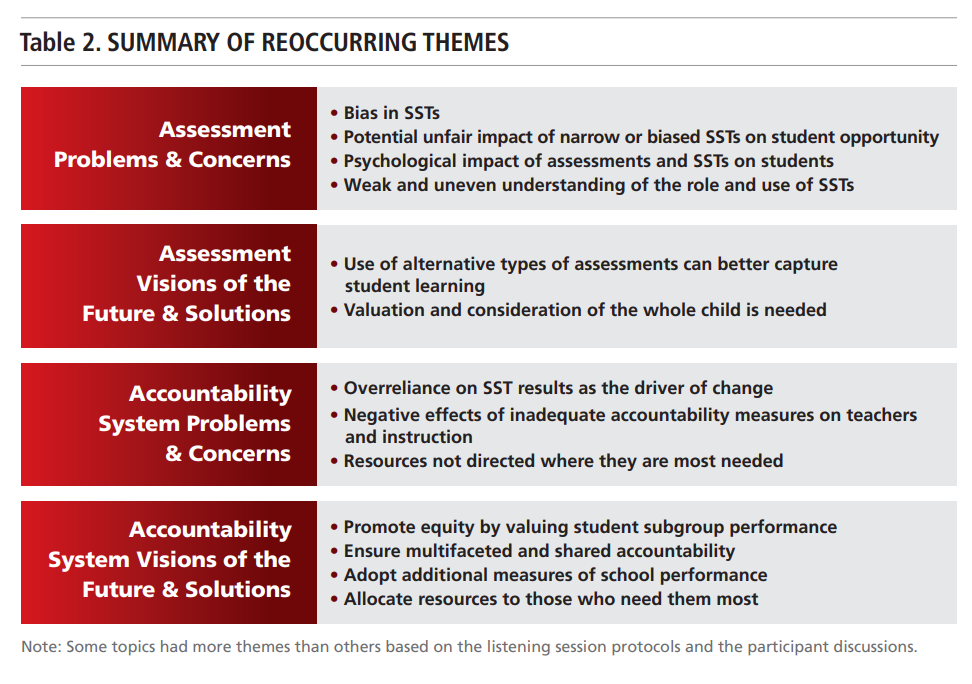

Phase I of the project kicked off in 2022, with 63 listening sessions that documented the perspectives of over 250 students, teachers, parents, civil rights advocates, researchers and other stakeholders. The listening sessions were complemented by a set of roundtable discussions with a group of 20 experts and leaders within the civil rights and education equity community. The findings from those conversations led to the publishing of a 2023 report titled Education Assessment, Accountability & Equity, which outlined emerging problems, solutions and emerging areas of agreement.

Now in Phase II of the project, convenings like the one in California are aimed at continuing to generate authentic dialogue and yield ideas for better assessment and accountability systems nationwide. In addition to hearing from leading experts, attendees participated in roundtable discussions aimed at the voices of stakeholders who are too often left out of policy conversations that impact their lives and experiences with the education system—particularly young people, their families and educators.

The insights gained from these discussions will undergird UnidosUS and the National Urban League’s federal advocacy platform on assessment and accountability.

Expanding definitions of success

Assessment and accountability systems were a key component of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), a 2002 law reauthorizing early federal legislation around equal access to education that came out of the Civil RIghts Movement of the 1960s. The goal of that law was twofold: enhance U.S. competitiveness in the global market and close the achievement gap between largely white, affluent students and low-income students who were disproportionately children of color. However, after NCLB’s rollout, many observed that the law created bureaucratic competition, punishing lower-performing schools and educators, making it that much harder to provide a comprehensive, whole-child approach to learning.

In 2015, Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which allowed states greater flexibility to set their own, more tailored achievement goals. But even with its flexibility, Gonez explained that ESSA has continued to put a strong emphasis on reading and math scores as primary markers of learning success, and less emphasis on creating engaging educational opportunities for other subjects like art, science and history.

“As teachers, we all know assessment is a part of our work. You have to see how your students are doing. You have to check for their understanding, but this heavy reliance on these particular tests can really crowd out the things that bring joy in education in a way that disadvantages our kids in high-needs communities,” she said.

This led one caregiver participant to opt their child out of testing altogether.

“I opted my child out of testing. My child has terrible test anxiety and I don’t want to stress my child,” they said. “It doesn’t measure the whole child. Why force it when it’s not necessary to measure the wholeness of a child?”

This perspective on testing highlights the need for schools to help parents understand the purpose of standardized tests and how results help schools and policymakers at various levels of government make decisions about resource distribution, academic interventions and education policy to ensure equitable outcomes for all.

Parent participants also expressed a desire for guidance on how to interpret their child’s test scores and obtain any academic support that may be necessary. That is, of course, if parents ever get to see their child’s test scores. Often, results are posted on online portals that require parents to have a device, Wi-Fi and tech skills to access them. Language barriers also limit the ability of some parents to interpret their children’s test scores.

The panel and roundtable discussions also revealed some support for creating alternative types of assessments. Student participants said they wanted assessments designed to uncover their diverse intelligences, such as musical and visual intelligence.

This effort is already underway in some school districts. As Anaheim Union High School District Superintendent Michael Matsuda pointed out, there is more to measure beyond academics.

“Even though we take the traditional [statewide] tests, we do not teach [to] the test in our district,” he explained. “We teach the whole child through what we call the five Cs: collaboration, communication, critical thinking, creativity and, probably the most important, is compassion. Beginning with self-compassion.”

Yolande Beckles, president of the National Association of African American Parents and Youth, added a sixth “C” to that list by mentioning the importance of culture.

“Have you, the teacher, done your homework to look at your class and look out for these beautiful Black and Brown children and go, ‘How do I teach so my children become engaged because they want to learn?’,” she asked. “From the moment you bring a cultural pedagogy conversation, we watch our children just come alive. That’s the education system I’m fighting to have in America.”

These observations support findings from Phase I suggesting that current standardized tests lack cultural representation, measuring knowledge related to White-American culture rather than that of those whose knowledge needs to be measured, which is an increasingly diverse school population.

The unique challenges for English Learners

California knows this challenge well, not only because it has one of the most diverse student populations in the country, but also the largest number of English Learners (ELs). Civil rights advocates contend that a supportive and engaging curriculum is critical to ensuring educational equity as well as building an inclusive society and competitive workforce.

“We care about how students are doing, but it’s also a matter of making sure schools are fulfilling their mission,” said Angelica Salazar, a senior policy advocate for Public Advocates, Inc, a non-profit law firm and advocacy organization addressing systemic poverty and racism through the strengthening of community voices in public policy.

She noted that education is almost always the number one expenditure in the state– about 37% of the annual budget, but wondered what other resources need to be provided to ensure the state’s student population can reach its full potential.

Xilonin Cruz-Gonzalez, deputy director of Californians Together, a statewide coalition focused on championing the success of multilingual learners, reminded the audience that California was a key player in ensuring ELs have specific support under federal law.

Xilonin Cruz-Gonzalez, deputy director of Californians Together, a statewide coalition focused on championing the success of multilingual learners, reminded the audience that California was a key player in ensuring ELs have specific support under federal law.

This legal precedent occurred 50 years ago when the Supreme Court ruled in Lau v. Nichols that failure by the San Francisco Unified School District to provide supplemental English language instruction to non-English speaking students was a violation of their civil rights because it deprived them of access to a meaningful education. The lawsuit was led by a group of Chinese immigrant parents who argued that their children needed access to education in a language they could understand.

In 2016, California voters overwhelmingly voted in favor of repealing Proposition 227, an 18-year-old law that severely restricted bilingual programs in favor of English immersion. Proposition 58 passed with 73.5% support, paving the way for a new era of multilingual education. This was a watershed moment for California’s 1.2 million English learners (ELs), of whom 82% speak Spanish. The State Board of Education then passed the English Learner Roadmap Policy in July 2017 to provide guidance to local educational agencies (LEAs) in order to welcome, understand and educate the diverse population of students who are ELs attending California public schools.

But as Xilonin Cruz-Gonzalez pointed out, many parents of EL’s still feel fearful of how filling out a home language survey could stigmatize their children. They are often unaware that schools use the survey responses to identify students who may need supplemental English instruction.

“We need to think about what kind of systems we are setting up,” she said, noting that making families of ELs comfortable with how they are identified and labeled is critical to ensuring those students get the support they need.

Although the convening took place over just a single Saturday, Jenny Muñiz, senior policy advisor at UnidosUS, believes it was very fruitful. “It provided a rare opportunity for meaningful dialogue between individuals who usually aren’t in the same room,” she said.

Following this event in California, UnidosUS and the National Urban League hosted another convening in Cleveland, Ohio, and planning is underway to hold one in a third state this December. These convenings will inform the policy recommendations that they will ultimately deliver to lawmakers in Washington next year.