The 50th anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court Case Lau v. Nichols explores how the outlook has changed for English learners

During May, which marks Asian Pacific Heritage Month, UnidosUS takes time to reflect and honor the significant role that Asian Americans have played in advocating for language rights in education that benefit all multilingual students.

In her forthcoming book, Lau v. Nichols and Chinese American Language Rights: The Sunrise and Sunset of Bilingual Education, Purdue University Language and Literature Associate Professor Patricia Morita-Mullaney writes how the U.S. government’s passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which put a 100-year ban on Chinese immigration to the United States, contributed to stereotypes of Chinese and other Asians as perpetually foreign. At the same time, she notes that their culture of studiousness and hard work has often stereotyped them as a racial bourgeoisie or “model minority” that lacked no support in the education system. And yet, it’s thanks to Chinese Americans fighting these laws and stereotypes that the United States’ five million English learners have legislative tools to fight for the support they need to have equal access to public education in a linguistically and culturally relevant way.

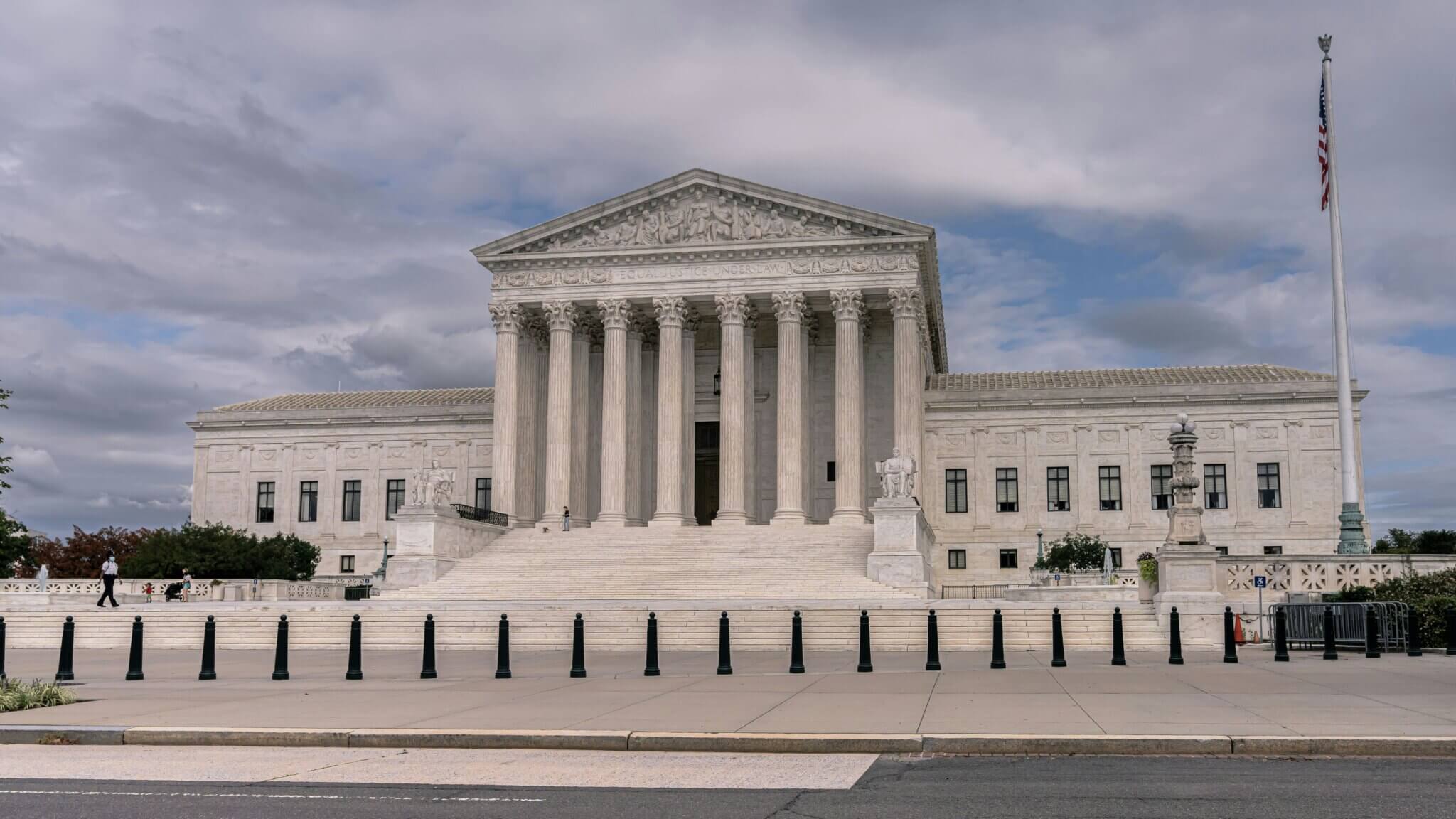

“Lau v. Nichols (1974) contested that the San Francisco Unified School District’s failure to provide adequate and appropriate instructional programming to 1,800 students of Chinese ancestry who did not speak English denied them a meaningful opportunity to participate in public education. Lau v. Nichols demonstrated that this lack of provision was a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which discriminated against the Chinese community on the basis of national origin, a proxy for language rights,” Morita-Mullaney wrote in the introduction to her book, which will be published in August of 2024.

Morita-Mullaney grew up in a Japanese American family in a nearby Bay Area school district. While she was not able to gain full proficiency in her ancestral language, her later fieldwork as a student in an intensive Central America Study and Service Program through Whitworth University in 1991 honed her Spanish. It also instilled in her a lifelong commitment to helping refugees, immigrants, and other multilingual students maintain their home languages while learning English, ensuring they are understood, appreciated, and supported as they move through the U.S. school system.

“The Supreme Court Case of Lau v. Nichols (1974) set [the]stage for English and bilingual language programming for multilingual students throughout the U.S. After its passage, Lau remedies were put in place throughout the U.S. where schools had to furnish resources and instruction that were more accessible to multilingual students, taking on forms of English language teaching and bilingual education. In the varied fields of language teaching, Lau is regarded as setting [a] legal precedent for the provision of a bilingual education on a national scale,” she added.

Celebrating Lau v. Nichols’ 50th Anniversary

On January 22, 2024, Morita-Mullaney joined other prominent Asian and Latino bilingual education advocates for a webinar sponsored by Claremont Graduate University and the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA) to celebrate Lau v. Nichol’s 50th anniversary to reflect on its historical impact and contemplate what challenges continue.

In her portion of the webinar’s panel discussion, Morita-Mullaney noted that during teacher layoffs immediately following the passage of Lau in the mid-1970s, “Chinese Americans were able to keep their jobs because of Lau, and African American teachers were able to keep their jobs because of Brown” because Chinese Americans involved in Lau v. Nichols risked their careers to help build a framework not just for language rights but all sorts of other education and voting rights.

The other panelists and event organizers shared Morita-Mullaney’s appreciation for the Lau v. Nichols plaintiffs. Today’s rapidly growing and diversifying EL population represents 10% of U.S. public school students, and Latinos, who represent most of those students, are some of the biggest beneficiaries of this landmark case.

“Being multilingual allows us to compete in the global economy, have better jobs, higher pay, and stronger creativity and problem-solving skills,” said Monserrat Garibay, U.S. Assistant Deputy Secretary of Education and Director of the Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA) during her keynote address. “This is a reminder that there are laws and policies already in place to ensure our English learners receive the education that they need the way that they need it in order to be successful in our schools.”

Lau’s Legacy of Advocacy for all ELs

Lau Plaintiff Lawyer and retired Santa Clara University Law School Professor Edward Steinman said there’s nothing in the world that can’t be legislated if the will is there to do it.

“The real problem is political and attitudinal,” he said.

Celina Moreno, President and CEO of IDRA, said that while her organization believes that students should not have to abandon their home language to succeed in school, old tropes continue to perpetuate old attitudes in education.

“Some have the mistaken belief that a student’s language makes for student underachievement,” she said, countering that “underfunded schools, bad policies, and inadequate educational practices make for underachieving students.”

Shantel Meek, executive director of the Children’s Equity Project, is a staunch supporter of promoting bilingual education at every level, including early childhood.

“Decades of research prove that access to high-quality early education is associated with every outcome you can imagine,” she said. However, she also reminded the audience that the United States is the only United Nations member country not to ratify the rights of the child and that children have virtually no rights to any of these things until they join the U.S. K-12 system.

The situation is especially daunting in her home state of Arizona, the sole English-only law in the nation that is still standing, where Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne filed or pushed to file several lawsuits against dual-language immersion (DLI) programming for multilingual learners. Under Arizona’s Proposition 203, the state’s English-only law, ELs are required to spend two hours of their school days in structured English immersion programs unless schools obtain a burdensome DLI programming waiver. Attorney General Kris Mayes, who was named as a defendant in Horne’s original 2023 lawsuit, has consistently maintained that only the Arizona State School Board can decide if a school district isn’t complying with the law.

Martha Hernandez, executive director at Californians Together, said California’s 1998 English-only instruction law Proposition 227 proved to be highly unpopular and unsuccessful. During and after its eventual repeal in 2016, organizations like hers have worked to make ELs more visible by advocating for policies such as the 2017 English Learner Roadmap, which paved the way for stronger multilingual education.

“English learners must receive comprehensive instruction that includes all the elements of literacy, including meaning, making language and vocabulary development, effective expression, including writing, content, and background knowledge in addition to foundational skills, and we cannot forget the importance of oral language,” she said.

Kenji Hakuta, a Lee L. Jacks Professor Emeritus, Stanford University, drew upon all of these insights and concerns by noting that future policy and advocacy efforts should center on raising the bar on Lau v. Nichols by centering on holistic child development. Hakuta explained that these efforts should expand far beyond language acquisition and advocacy to include social and emotional learning, literacy that covers math and sciences, and a concerted effort by advocates to develop cross-cutting partnerships that streamline the research and development of best educational practices so that they don’t become duplicative.

In so doing, he believes that multilingualism at home and in schools will start to be normalized, which in turn provides greater legitimacy for dual-language immersion in early childhood, a special seal of biliteracy for high school graduates, and greater civic engagement for non-citizens.

But he also hailed the efforts that have been ongoing for so many years.

“I think we all have benefited from Lau because we’ve gone beyond what the letter of the law said, and we have taken collective action in various levels of government, levels of policy, and levels of practice,” he said.

Lau: A Spark Plug for Better Research Policy and Practice

San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) Associate Superintendent Karling Aguilera-Fort has had the privilege to see just how much Lau v. Nichols changed the school system first involved in the case. She said this has included constant input from Chinese American education experts, especially SFUSD Special Assistant to the Superintendent Christina Wong. She assisted in the sunsetting of the Lau consent decree, which was in force from 1975 to 2019.

Today, the district is working on a concrete plan for helping all teachers learn the many facets of its latest multilingual roadmap, one that asked questions such as:

“How will it be implemented? What are the strategies? How will our English language development be disseminated and explicitly supported throughout our entire set of schools?” Aguilera-Fort said.

Meanwhile, in the multilingual metropolis of Chicago, Pedro Martinez, CEO of Chicago Public Schools, said the development of a culturally responsive curriculum has contributed to a 25% increase in attaining seals of biliteracy for the district’s 80,000 multilingual graduates, progress that could aid the increasing numbers of migrant students in pre-K through fourth grade.

“We’ve shown in research that when our students finish their transitional bilingual programs, they begin to outperform other peers,” said Martinez. “What it takes is constantly having the conversation of (about) the value of culture, the value of language.”

In her 30 years of teacher preparation for bilingual students, Cristina Alfaro, Associate Vice President for International Affairs and Executive Director for San Diego University’s Center for Equity in Biliteracy Education Research, has had to navigate “around and through anti-immigrant social [and] political ideologies, and survive a lot of the incessant political attacks,” she said.

This struggle has required developing a “critical consciousness” for teachers to care about the communities they serve. At the same time, it requires careful observation of a trend in what many call language gentrification in which families with more economic and social privilege want their children to be bilingual. The key, she explained, is to make sure the less privileged students continue to obtain the support they need.

Eugene Garcia emphasized the great diversity of the English learner population, which comes from all different parts of the world and has many different ways of thinking about language and education.

“I would say what we are learning basically is that Lau was a spark plug,” he said, adding that 50 years later, “We have better research. We have better practice.”

He echoed Meek in stating that multilingual support should start with ensuring very young children learn their home languages.

“You cannot separate children and family from their language,” he said, reaffirming that these families need to know what possibilities exist in the educational system.

Michael Roberts, superintendent of the Osborn School District in Phoenix, Arizona, added that educators need to be aware of not only the legislative challenges of their state but also the culture of the school system in which they work.

“Make sure that you understand the values of the school districts that you’re going to work for. We’ve managed to do this difficult work for 25 years, providing access to our students through lawsuits and all this complex navigation,” he said.

Magaly Lavadenz, the Leavey Presidential Endowed Chair and Executive Director of Loyola Marymount University’s Center for Equity for English Learners, said it starts with teachers doing their research on potential employers.

“Make sure that you equally interview the school site, the administrators, to find out what kind of support and resources they have from the beginning,” she said.

“Watch videos, watch the lessons, look for resources. There are organizations in every single state,” added Aguilera.

Moderator Oscar Jimenez-Castellanos, a senior research fellow at Claremont Graduate University, commended the panelists for their comprehensive approach to maintaining the educational and civic engagement values laid out by the case of Lau v. Nichols while pushing all participants and the audience to keep asking questions.

“What happens at the leadership level? What happens at the teacher level? Those are the folks that are actually making what is called the living law, right? It’s going above and beyond,” Jimenez-Castellanos said.

In his concluding remarks, DeLacy Ganley, Dean of the School of Educational Studies at Claremont Graduate University, reached back to the spirit of the Chinese Americans and advocates like Steinman, who came alongside them in their struggle.

“One of the resounding theses that comes out of it is that if there’s a will. There’s a way,” he said.