Artist Brujo de la Mancha Teaches Students to Make Art From Their Traditional and Modern Worlds for Self-Expression and Discovery

Philadelphia-based Mexican American artist and cultural educator Brujo de la Mancha has had many difficult experiences to in his life. He was raised in a broken home, and often found himself searching in a somewhat fragmented mestizo culture where few identify entirely as Indigenous or not. He yearned to be an artist, but his working-class family warned him that vocation would leave him flat broke.

“I always want to be an artist because I always thought about how art helps you, but Mexico was difficult. There was no money, so I was always struggling,” he says. By the time he was a teenager in the 1990s, that struggle led him to dress as a rocker and a punk, joining a protest movement to stop efforts to privatize the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). After getting arrested and experiencing police violence, he no longer felt safe. He needed a new community and new avenues for promoting humanitarian causes.

He left Mexico City and went traveling through Mexico’s most traditional Indigenous communities to learn how they and their ancestors have spent generations pulling elements from their natural environment to make art, such as wood for carving and clay for sculptures. Then one day walking on the beach in Oaxaca, he noticed a series of fish bones, picked them up, and turned them into a pair of plug-style earrings. Next, he and his friends were finding deer horns and turning those into jewelry.

“Every time I touched something like that I thought ‘oh, I can make this happen,” he says. Something about art helps you to be who you are, and you have to let it out. You have to obey that part of you as your natural expression, but it also depends on how you grew up.”

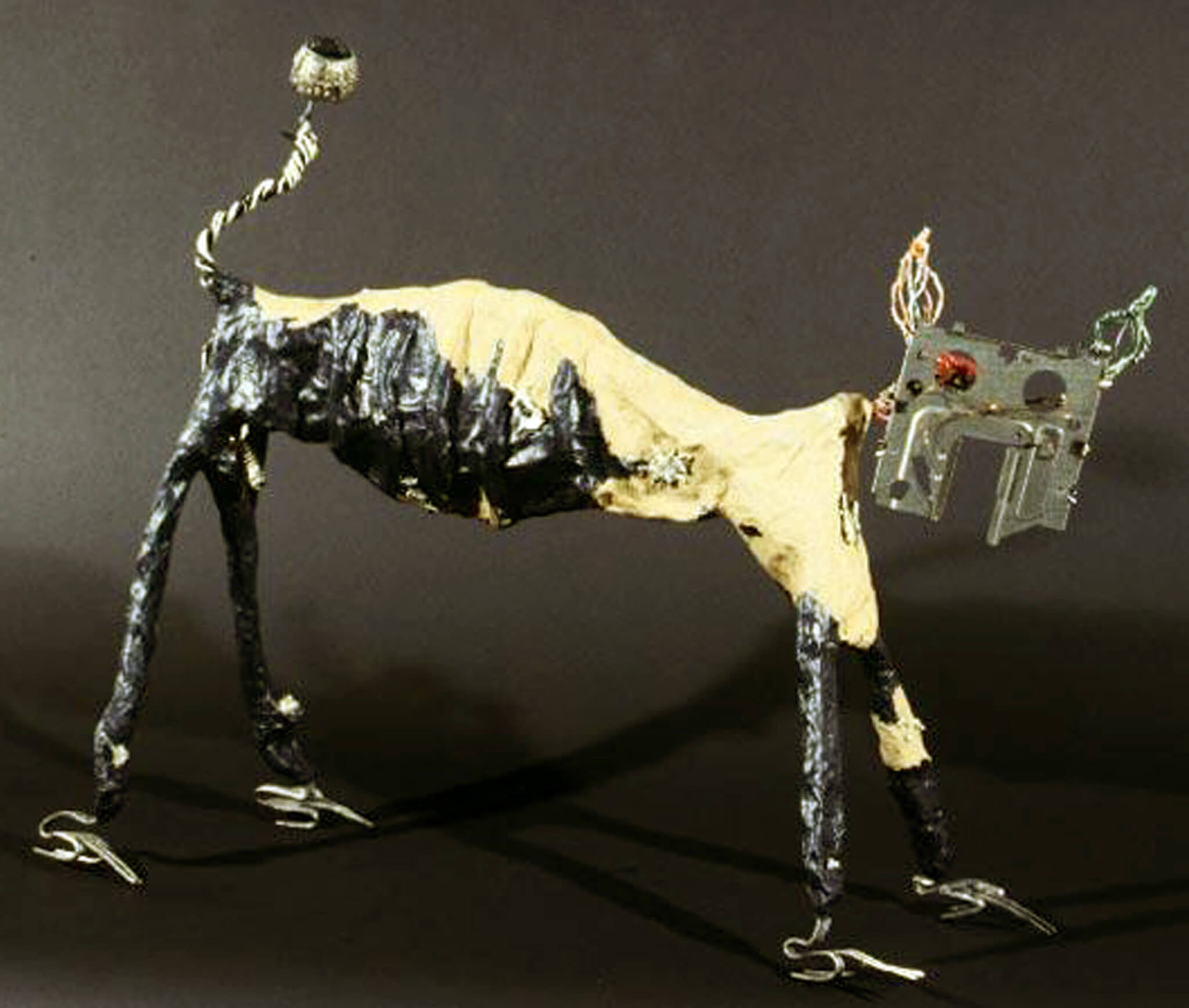

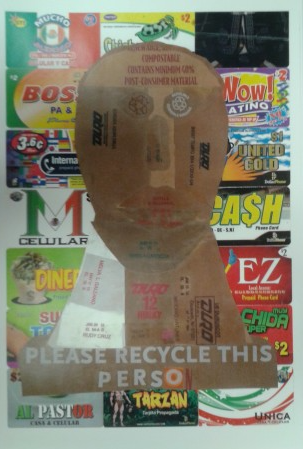

Upon emigrating to the United States in the late 1990s, he began to consider how he could explore the various facets of his mixed and modern identity by merging those materials with debris from the industrialized world. Today, the Philadelphia-based, multidisciplinary artist is known for his many public murals, his paintings, and a collection of mixed-media sculptures, which often combine computer parts and papier mache to create animals, people, and deities like the ones he found while exploring his Mexican heritage.

Among other public activities, he uses these works to teach school children to delve into and express their own unique identities.

“I don’t have a specific theory or formula because making art back then was not very well appreciated,” he says, and yet, that’s precisely why he wants students to harness different traditions and pieces of their heritage to become more industrious versions of themselves.

“Sometimes it’s not about making money but about exploring the benefits of self-expression that come through art,” he says, noting that art of any kind can help students know their cultural identities better.

One of his favorite places to start is the culinary art since food is central to everything from altars to family celebrations, and recipes are often adapted to new surroundings and contexts when people migrate or fused with other traditions as cultures interact. As such, he suggests engaging students in conversations of the origins of particular foods such as vegetables, grains, and fruits, especially ones that might reflect their ancestry.

For example, Mesoamerican students might want to explore dishes that use tomatoes and cilantro, students of South American descent could try making a dish with Andean potatoes or quinoa, and Caribbean students might consider how foods such as cassava or malanga existed before times of colonization and how enslaved people from Africa brought foods like okra and yams to the Americas.

De la Mancha says that altars, whether for November Day of the Dead celebrations or an ongoing memorial to the dearly departed, are an outpouring of artistic, cultural, and spiritual expression.

“I do altars because I want to make an offering to ancestors, energies, or souls that are wondering here with us,” he says. “Anything I put on my altars counts when it’s offered from the heart.”

He is also a firm believer in the art of moving one’s body through dance. In 2003, for example, he co-founded the Ollin Yolitzlti Calmecac (OYC) dance troupe with Daniel Chico, an Indigenous Mexican whose first language is Nahuatl. It was Philadelphia’s first Aztec dance troupe, and the community interest it generated was so positive the two founders turned OYC into a nonprofit organization. Through dance and music, De la Mancha says, students can find expression in movement, in rhythm, and in the tone and cadence of ancient words uttered through singing.

But ask him for a favorite art piece, painting, or arts project and he’ll tell you he has none, that each creation is precious and sacred in its way, so long as it is rooted in a sincere search for self-discovery. De la Mancha wants students to learn all they can about the deep roots of their heritage and those of their classmates, and he also wants them to feel that their identities can be built out of all kinds of inspiration.

What is authentic to De la Mancha? That which builds upon a journey of cultural self-discovery, on the exchange not appropriation of cultures, and on the importance of recycling for all kinds of preservation.

“As long as you don’t copy, it’s authentic,” he concludes.

Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS senior web content manager and the editor of ProgressReport.co.