A Youth Book Company Helps Immigrants, English Learners, and Other Undocumented Students to Write, Illustrate and Publish Stories

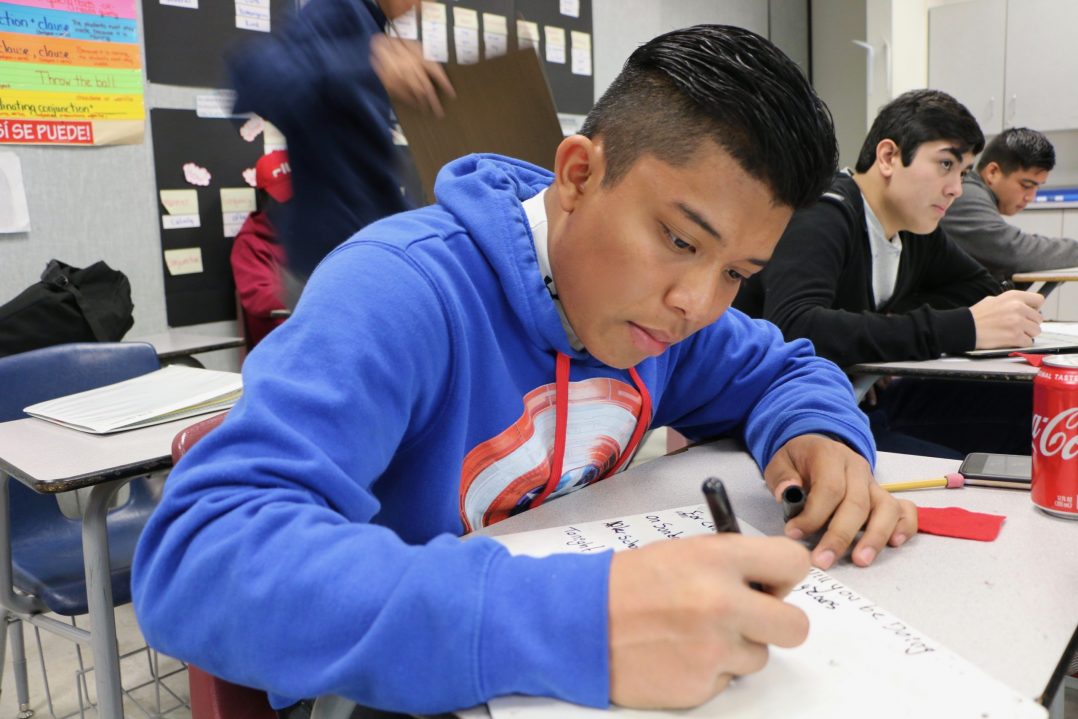

In 2013, Santos Amaya found herself in a U.S. classroom feeling alone, confused and disillusioned. The dream of a quality education had driven her to take off on her own from her native El Salvador as an unaccompanied 15-year-old migrant, and after several harrowing attempts across Central America and Mexico, she had finally made it.

She wasn’t the only one. According to DHS’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the number of unaccompanied child migrants in the United States increased from almost 39,000 in 2013 to close to 69,000 in 2014, and few in the American school system were prepared for their arrival.

“I remember the professor asked me ‘what is your name’ and I just smiled because I didn’t know what she meant,” recalls Amaya. Then came the F that she got on her science homework. She didn’t know what that meant either. When she went to ask the teachers in Spanish, the only thing she could decipher was that she had a lot of room for improvement.

“I felt really frustrated, and for a moment I thought school’s not for me.’”

Voices Without Borders

While changing schools helped a little, the biggest boost to her confidence and academic outlook came through a 2016 initiative of the Latino American Youth Center, an UnidosUS Affiliate based in Washington, DC. That year, the program teamed up with local schools to invite students to fulfill their community service hours by participating in its Latino Youth Leadership Council (LYLC). The LYLC later partnered with Shout Mouse Press.

While changing schools helped a little, the biggest boost to her confidence and academic outlook came through a 2016 initiative of the Latino American Youth Center, an UnidosUS Affiliate based in Washington, DC. That year, the program teamed up with local schools to invite students to fulfill their community service hours by participating in its Latino Youth Leadership Council (LYLC). The LYLC later partnered with Shout Mouse Press.

The local publishing company’s mission is to allow young readers to see themselves represented in print. They accomplish that powerful feat by allowing students of rarely represented backgrounds to write and oversee illustrations of books and graphic novels for young readers. For students who are immigrants, incarcerated, pregnant or parenting, those reflections can have a resounding impact.

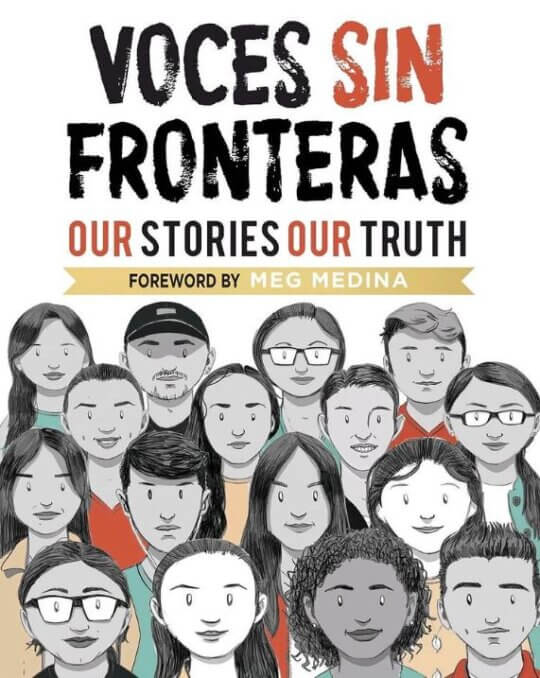

“In El Salvador, I was torn between the comfort I felt with my family and knowing that I wanted to shine brighter,” she wrote in “I Cross Barriers to Change Myself,” the first short story featured Shout Mouse Press’s most popular book “Voces Sin Fronteras: Our Stories, Our Truth”.

Beyond Borders Bilingual Kids’ Books

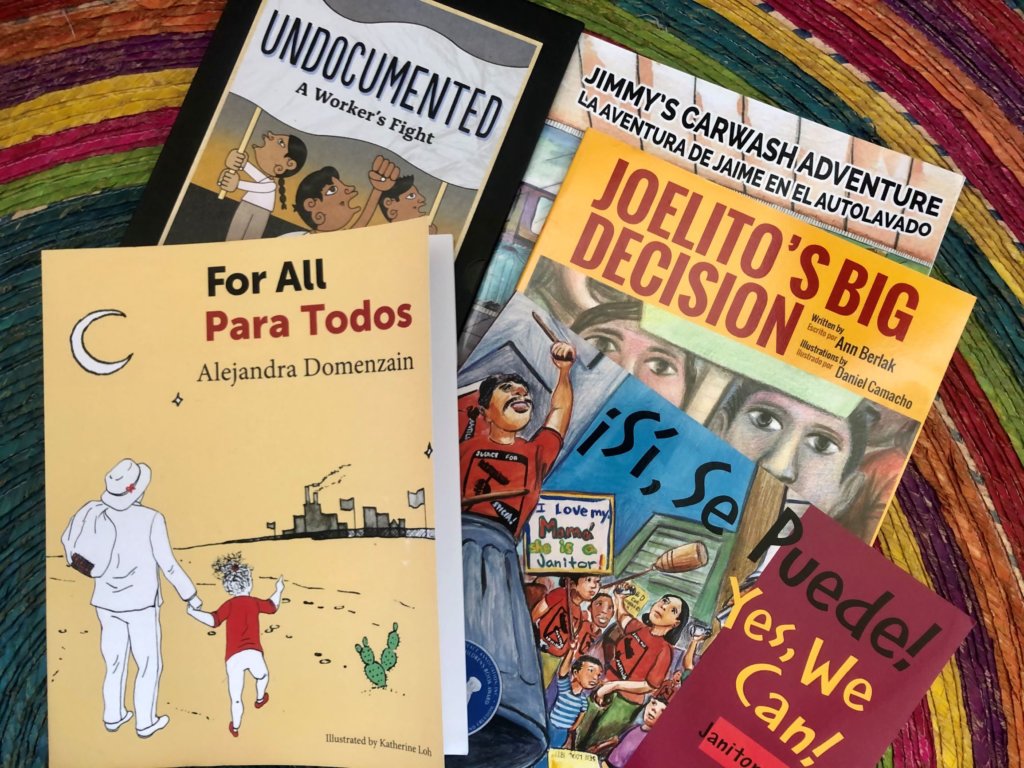

Amaya is one of thousands of young people with similar backgrounds to finally have a platform for sharing their stories. Shout Mouse began in 2014 after noting that children from these under-represented communities accounted for more than 50% of the country’s youth population but appeared in less than 10% of the literature aimed at people in that age group. Today, the publishing company partners with about seven youth-focused organizations to produce books, and its collection of 500 books are promoted and distributed through Apple and the UnidosUS partner FirstBook.

“We were very aware of how the stories youth were surrounded by shaped their understanding of their own possibility and potential, and also shaped everyone else’s understanding of their potential and possibility,” Shout Mouse Press Founder Kathy Crutcher told ProgressReport.co.

She noted that a lack of diverse literature is also “deeply problematic for white children who are accustomed to seeing themselves centered as the heroes of the stories.”

Thanks to these partnerships and the growing demand for diverse youth literature, Shout Mouse Press has more than 100,000 books in circulation across the country. “Voces Sin Fronteras” is by far the most popular for teenagers, but there are many other books in the collection aimed at engaging younger audiences.

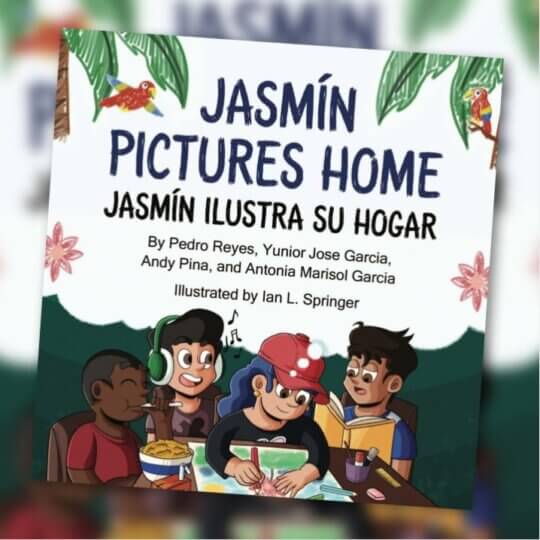

In the book “Jasmin Pictures Home,” LAYC authors Pedro Reyes, Yunior Jose Garcia, Andy Pina and Atonia Marisol Garcia tell the story of a young Honduran immigrant who can’t decide what to do for their school’s Culture Night. But then she gets to thinking about her friends and the activities they miss from their homelands.

“What we wanted to do with this story when we chose it was to say ‘well these kids are Latinos. Let’s make it about how they feel and how they miss where they came from,’” Pina said in an Apple video about the project. “And to take it a step further, we decided they would get something that would help them not miss their home countries as much.”

In the book, their character Jasmín takes that step by painting an image of each of her immigrant classmates in their respective scenarios. At the end of the book, the authors invite the readers to draw an image that reminds them of their own home.

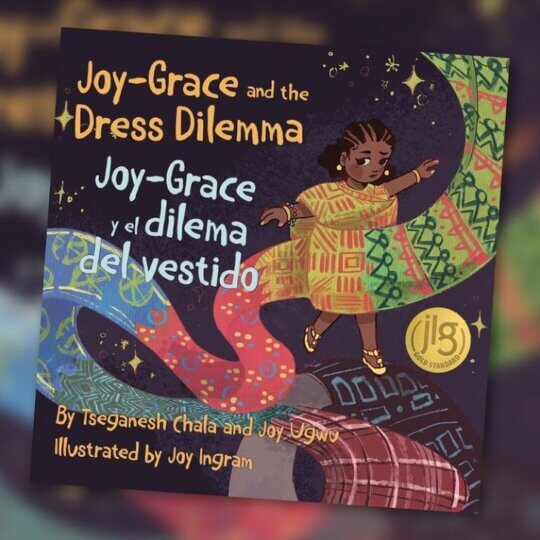

The book “Joy-Grace and the Dress Dilemma,” written by Tseganesh Chala and Joy Ugwu combines cultural influences from their childhoods into the story of a very expressive American schoolgirl of Ethiopian, Nigerian and Jamaican heritage. Joy-Grace, who is also a budding fashionista, has no problem deciding she’ll wear her show-and-tell piece to her school’s Culture Day. Various members of her family have given her dresses from their respective corners of the globe, but the question is, how can she deal with the pressure of deciding which dress to wear if it means part of her heritage and her family won’t get represented?

“I go to my room, dragging my feet. I throw my tibeb on the bed. They don’t get it! I can’t just pick one. I don’t want to disappoint anybody. I shove the clothes into a pile,” Joy-Grace tells her reader, the tibeb referring to a traditional Ethiopian dress. “Then I look at the dresses and I think they kind of go together in a funny way.”

Suddenly the future fashionista is in full creative mode.

“I got it! I grab my pencil case and my design book! I start to draw. I draw and draw. This will be my greatest creation yet!” Joy-Grace concludes.

When she arrives at her school’s Culture Day, she twirls before her classmates and tells the reader how proud she is of all her cultures, and that now she knows she doesn’t have to choose just one.

The Joy-Grace story was an amalgamation of similar experiences the two authors went through as Chala is of Ethiopian descent and Ugwu of Jamaican and Nigerian descent, and just writing the book was cathartic says Ugwu, who went on to study psychology.

“It was wonderful to influence (childhood) development by creating children’s books where the main character looks like the readers and have experienced the same struggles,” she says. “That allows them to know that even though they’re different, it’s not bad.”

While most of the books were written in the United States, in 2014, Shout Mouse Press partnered up with a non-governmental organization helping trafficked youth in Haiti. In the book “Jenika Sings for Freedom,” a child author reflects on the experience of being indentured and exploited by family members with more financial means than her own immediate parents. That experience, known as restavek in Haitian Creole, is common but not unique to Haiti, and many children in the United States can likely relate.

“She cleans and she cries, and she suffers. But she continues to sing too because this is the only thing that keeps her going,” the book explains.

It takes more than singing to get her out of her predicament. It takes an adult willing to risk it all, including his own family ties, to help Jenika find her freedom and her voice. Ultimately it’s a story of hope at the end of a dark tunnel, a reminder of the tools children have to self sooth and the hope that in spite of all the world’s madness, there are still reasons to be hopeful and to believe trustworthy people still exist.

Pregnant and Parenting Students

There are many reasons why a teenager or young adult might go ahead with birthing and parenting a child when they are so young themselves, but it becomes an even more potent resource in a post Roe v. Wade time.

Over the past year, Shout Mouse Press worked in collaboration with 12 parent scholars through the nonprofit organization Generation Hope in Washington, DC to create a series of early childhood books called the Mini Mirrors series.

The books are aimed at inspiring both children and parents by showcasing parental experiences that are often underrepresented or seen as somehow deviating from the ideal. For example, in the book “Mamas Just Like You,” parenting college students Sinnah Bangura, Chae Eun Jung, and Marilyn Ramirez harness colorful imagery to note that there’s no ideal mom image, showcasing instead a wide array of moms engaging in different vocational educational activities.

“For all the mamas out there, we want you to know that there’s no right way to be a mom. You can be yourself and be proud of who you are because you are amazing!” The authors write at the beginning of the book. “If you rarely ever see yourself in children’s books, this one’s for you.”

Muslim American Youth

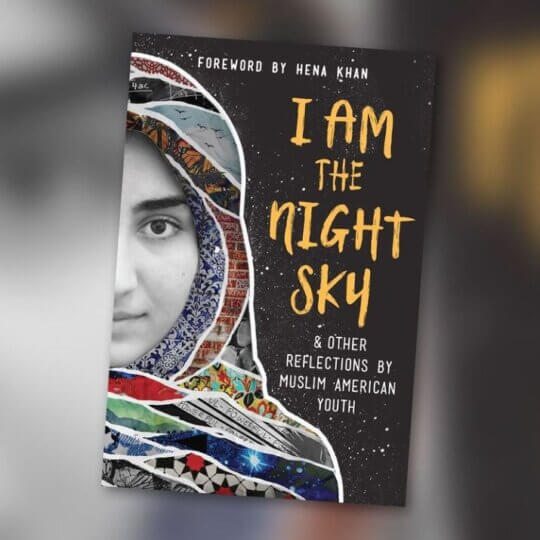

In 2017, the Trump administration put into place what became widely known as the Muslim Ban, a series of executive orders that prohibited travel and refugee resettlement from a variety of predominantly Muslim countries. Civil rights advocates across the country criticized the policy for contributing to a rise in xenophobia and intolerance. Two years later, in an effort to mitigate the damages of such actions, Shout Mouse Press recruited ten Muslim teenagers in Maryland to provide poetry, essays, artwork and stories aimed at breaking negative stereotypes and building greater cultural understanding.

“We realized we had been given an opportunity to show who we are because for so long nobody believed us when we told them. False narratives and demonization made us feel as if we had to defend ourselves, but we were tired of fighting, we wanted to make something of our own. So, we made this for ourselves and for our younger selves who grew up needing this book,” wrote Salihah Aakil, author of a short story titled “I Am the Night Sky.”

The first in the book, Aakil’s story asks why concepts of darkness or blackness should be associated with danger, fear and negativity.

“I have come to the conclusion that the night sky is my mother,” she writes, then asks how people could tremble at “something so similar to a hug. Something so encompassing and sheltering and strong.”

Incarcerated Youth

A history of racism, implicit bias, lacking opportunities and resources all contribute to higher rates of school discipline and dismissal among poor children and children of color. That in turn, contributes to higher rates of incarceration among this same demographic. In recognition of these issues, in 2021, Shout Mouse Press worked with incarcerated youth to create a poetry series.

In one poem, titled “My World,” an incarcerated writer named Jonas, talks about being born into and growing up in social and economic conditions that contributed to his serving time.

He speaks of the problems in his home and in his community but also of a “world full of so much potential, but the people have endured centuries of brainwashing that taught them to hate themselves.”

Books for All in Contentious Times

For UnidosUS, publishing companies like Shout Mouse Press provide a creative, artistic pushback in contentious educational times, ones in which those fearful of diversity have pushed for legislation banning topics such as critical race theory or ethnic studies.

“Stories that are told by young people who reflect the rich cultural diversity of today’s student population are essential to fostering a sense of belonging for those who don’t see themselves represented in mainstream literature,” says UnidosUS Education Policy Project Director Amalia Chamorro. “Courageous and authentic storytelling can be a powerful tool against the culture wars that seek to politicize school library catalogs and summer reading lists. By encouraging more young writers to create relatable stories that touch on their lived experiences, we can better cultivate a love of reading, strengthen literacy, and enrich learning.”

–Author Julienne Gage is a former UnidosUS Senior Web Content Manager who now serves the organization as a consultant.