The TPSeano Series: What Is Temporary Protected Status?

In the month headed into Congress’s August recess, much of the attention in the immigration space has been correctly focused on protecting the DACA policy that shields nearly 800,000 youth from deportation, pushing back on the Trump budget proposal, which would take funding for deportations to unprecedented levels, and picking up the pieces from the painful effects and consequences of the ramped-up interior enforcement on predominantly Latino immigrant families. Not to be lost in the shuffle, however, is another very important issue percolating in the not-too-distant background. Within the next six months, the Trump administration will be making decisions on the future of temporary protected status (TPS) designations that could impact over a quarter of a million Latinos from Central America, some of whom have been residing in the United States for nearly 20 years.

TPS is a humanitarian tool established by legislation giving the executive branch a way to provide temporary status to some of the most vulnerable populations in the country. Under TPS, people already residing in the United States may be designated for protection due to an ongoing armed conflict, natural disaster, or presence of extraordinary and temporary condition in their country of origin. TPS beneficiaries are eligible to work legally in the country and may apply to travel abroad for so long as the U.S. government determines that protected status continues to be warranted—a decision that is typically assessed 18 months after an initial designation or a preceding TPS extension.

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

It may helpful to think of a TPS designation, in a general sense, as a moving high-speed train. When the decision to designate a country for TPS is made, those who are eligible must get on the train before it leaves the station. For those who are ineligible or miss the window to apply, it is nearly impossible to jump on the moving train at any point after. Once on, however, people may continue to renew their protected status and work authorization, so long as their country’s TPS designation is extended, submit to criminal background checks, and pay an application fee to the government (currently around $500). For this reason, not all of those theoretically eligible for TPS have been able to acquire this status, but those who have, by the very definition of the TPS program, are not risks to public safety.

And some TPS beneficiaries—or TPSeanos as some refer to themselves—have been riding the train for many years following years of extensions by the U.S. government. In January 1999, the United States designated Honduras and Nicaragua for TPS following the destruction wrought by Hurricane Mitch, which struck the countries in October 1998. The government did the same for El Salvador two years later following the devastation brought about by a series of crippling earthquakes in early 2001. Every 18 months since their initial TPS designation—over 18 years ago in the cases of Honduras and Nicaragua, and 16 years for El Salvador—these Central American TPSeanos have reregistered with the U.S. government for protected status, all the while living lawfully in the United States, contributing to the economy and communities, and raising families.

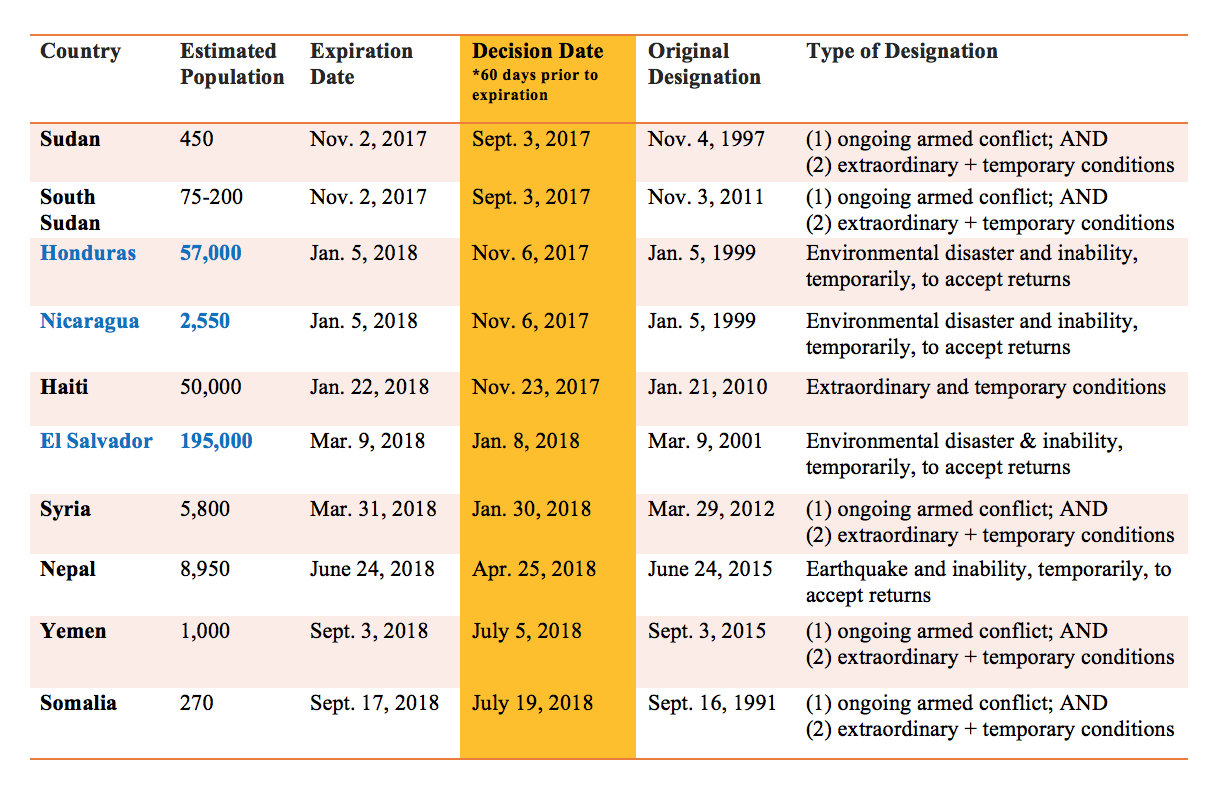

As the chart below shows, there are currently about 325,000 total people on TPS from among 10 protected countries. El Salvador with its estimated 195,000 TPS recipients, Honduras at 57,000, and Haiti at 50,000 together make up the overwhelming majority at just over 300,000. Together with the estimated 2,550 Nicaraguan TPS recipients, they are also the longest tenured.

Population estimates come from Carla Argueta, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues, Congressional Research Service, RS20844, Jan. 17, 2017, available at fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/RS20844.pdf.

Population estimates come from Carla Argueta, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues, Congressional Research Service, RS20844, Jan. 17, 2017, available at fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/RS20844.pdf.

Resources & Ways to Get Involved:

- Resources for Advocacy and Community Engagement by Allianza America

- The #SaveTPS Campaign website and videos