Broward County’s Black Lives Matter Alliance is Making History by Teaching Intersectional Civic Engagement to South Floridians

On February 1, a diverse group of organizers from Black Lives Matter Alliance in South Florida’s Broward County kicked off the first day of Black History Month, also known as Freedom Day, with a rally for social justice. It also provided a strategic opportunity for teaching diverse members of the South Florida community about civic engagement in all its forms, including protesting, voting, lobbying, and developing emotional support systems for confronting structural racism, hate, and police brutality.

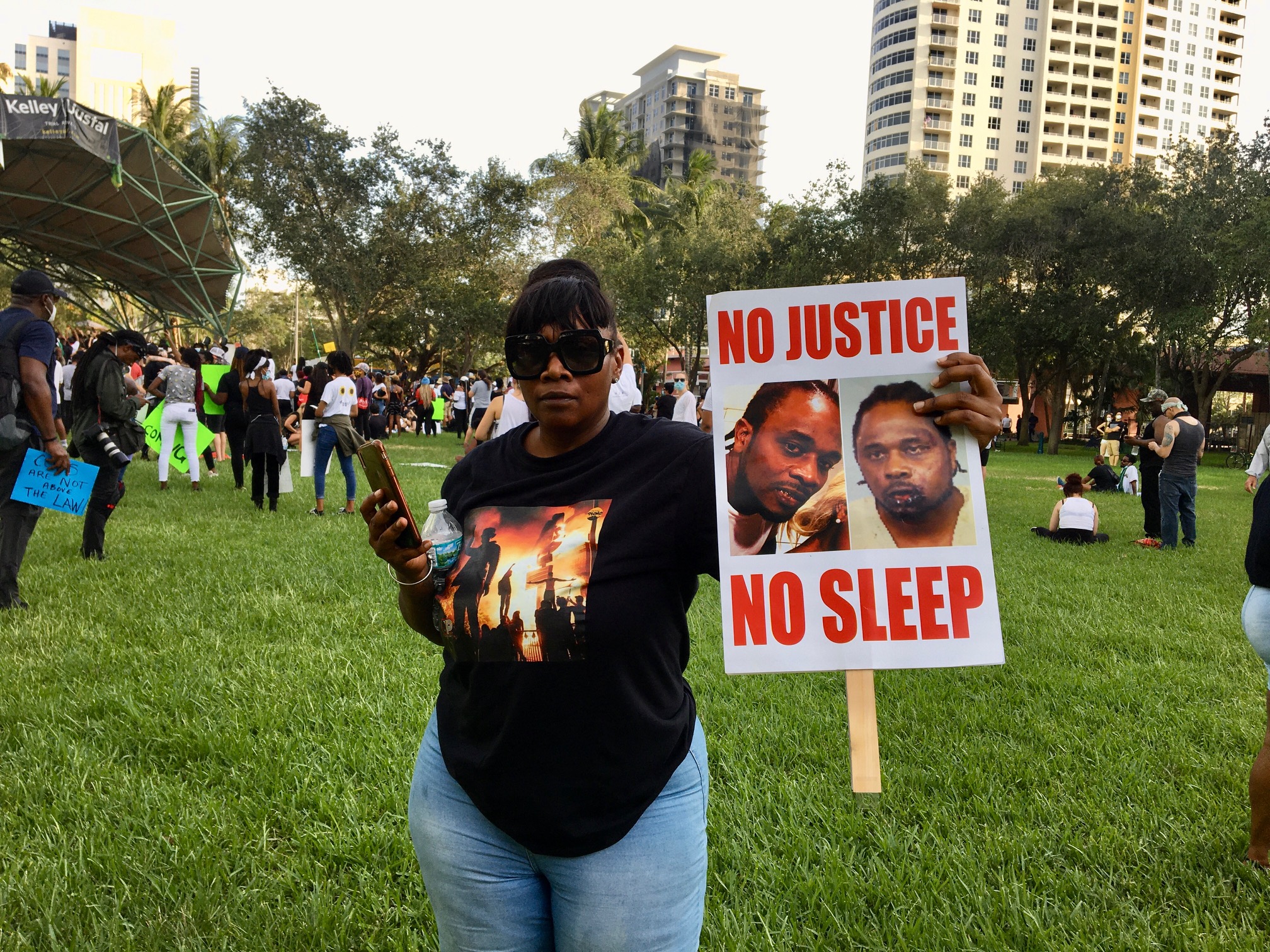

As if to illustrate the need for a reckoning, the event was held at Bubier Park in Fort Lauderdale, where last May, participants of the same alliance who had used the park to protest the police murder of George Floyd, were ambushed by police spraying them with tear gas and rubber bullets as those protestors peacefully walked from the park to a public garage about a block away. Many saw that ambush as yet another symbol of what they were protesting—the disproportionate use of force against people of color, and the double standard was certainly highlighted by the fact that police hardly used any force on the group of mostly White protestors who stormed the U.S. Capitol building in an all-out armed and deadly insurrection on January 6.

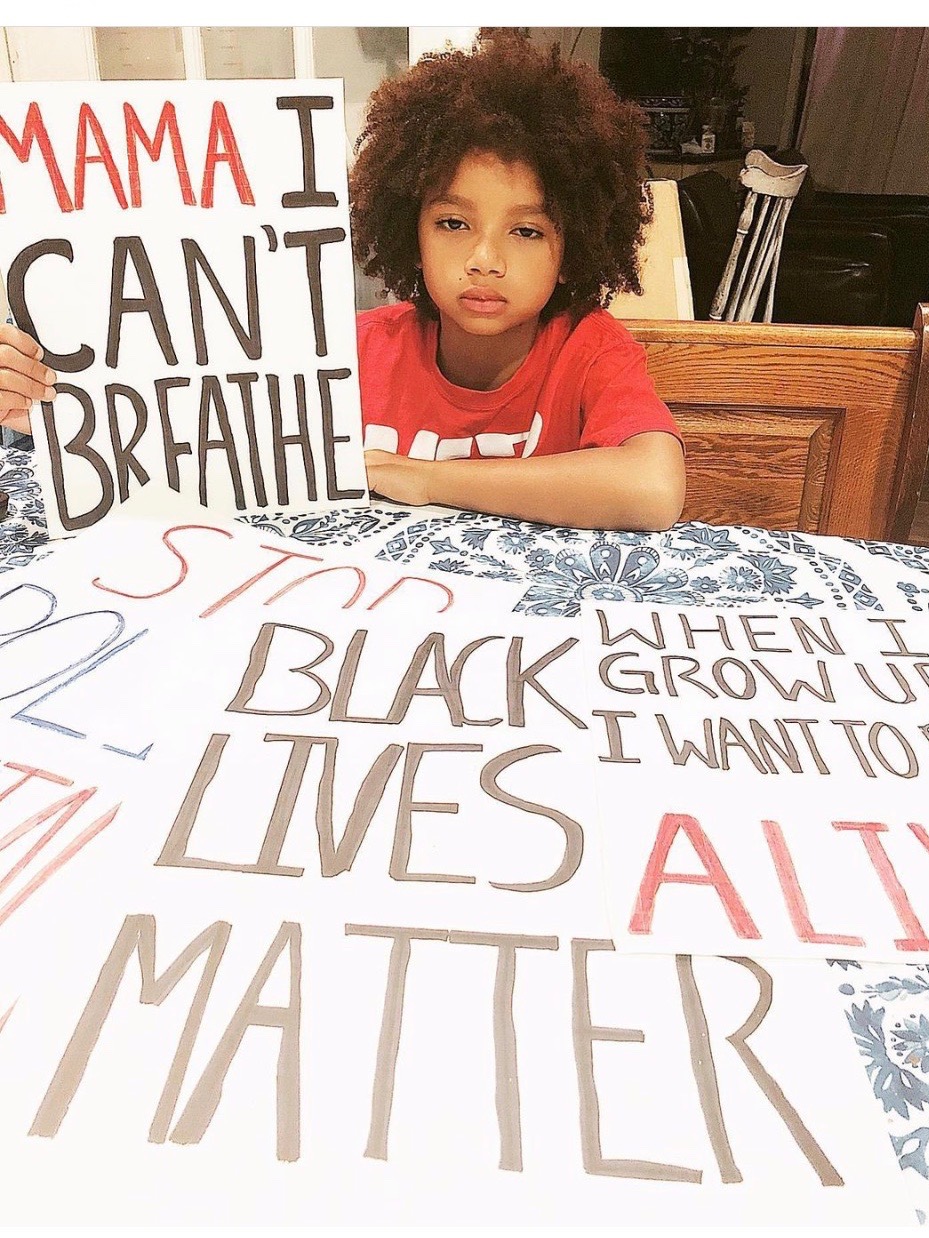

“It’s acknowledging, validating, recognizing that Black people not only have the right to survive, they have the right to live, to thrive,” says Jamaican American Patrice Walker, a Broward County BLM Alliance leader who has been organizing group therapy sessions called “emancipation circles.” The circles she leads draw from Black traditions such as drum circles and storytelling, and provide an opportunity to acknowledge Black lives lost that didn’t make it to hashtag fame the way cases such as Treyvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd did.

“One thing about trauma is that it doesn’t care whether or not you want to remember it. It’s there, and a lot of times it’s not just from our own experiences, but rather it’s passed down,” she says, but notes that the same can be said of cultural assets. “From a healing aspect, these activities remind us that we were human before we were enslaved. That period that was brutal and painful, and there were also things we used to do to find healing throughout it. How else would we be resilient in the first place?”

And yet, being resilient doesn’t make a person invincible—police killings and other forms of violence, health disparities and the mental anguish of White supremacy have worn Black folk down for centuries, to the point where Walker worries one of the biggest risks for those who survive everything else is suicide.

Intersectional support is key taking on all these problems and Florida is just the place to explore what that can look like, say organizers. This peninsula has been colonized by Spain, England, France, and United States, all of whom share responsibility for wiping out the area’s indigenous population and enslaving Africans to work the lands. It’s a land where indigenous peoples forced out of other parts of the continent were sent to live, and it has also served as a refuge for many immigrants and refugees seeking shelter from economic and political caused by parallel forms of colonization and imperialism across Latin America and the Caribbean.

Showing Latino Solidarity

That growing awareness of injustice against America’s Black and Brown communities led Carlos Naranjo to help found BLM Alliance Broward as an activist who is not Black but identifies as a Latino, an immigrant, and a Colombian –American.

“I got really interested in those intersections of injustice—being an immigrant, but also in the context of the deep structure of historical racism of this country,” he says. “It’s about how do I find some commonalities and show solidarity with the African American community and what they face.”

Naranjo also works as a community organizer for Florida Rising, a state-wide multiracial organization focused on advancing economic and racial justice through year-round engagement in elections and policymaking, so he has been able to leverage his activism in both organizations to also raise awareness on issues such as racism, public safety, and free speech.

Together, organizations like these are working to highlight cases of police brutality across South Florida, regardless of whether they become a national news story. And while he says it’s important to continue centering the conversation on violence against Black lives, he says there is an effort to create awareness around cases where law enforcement has perpetrated violence against Latinos and immigrants as well.

This year, one of their biggest challenges will be how to address a bill filed in late January and championed by Republican Governor Ron DeSantis which many believe could seriously undermine the right to do exactly what they’re doing: exercising their right to protest and organize. If passed, HB1 would increase penalties for illegal actions during riots, make it a felony to destroy or vandalize a Confederate memorial, and place limits on a city’s capacity to move funds from police to social programs.

“We feel that highlighting some of those other cases is essential to forming that really deep, broad coalition of Black and Brown families,” Naranjo adds.

He has also been helping to build out emotional emancipation circles in Spanish for the Latino community, and considers them key for a person like himself who was raised to project himself or as a “big, macho Latino.”

“There’s so much stigma and drama around talking about these things and putting your business out there. But I think those intentional, more private spaces for acknowledging them, not only intellectually, but in your heart is a profoundly, profoundly revolutionary way of doing this type of work,” he explains.

At the national level, the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement has helped UnidosUS to further its own role in engaging the U.S. Latino community around acknowledging, confronting, and dismantling systemic racism. This process has recently included: a preamble about systemic racism to our major paper in June 2020 on the impact of the coronavirus on the Latino community, discussing issues of racial justice at our 2020 Annual Conference, and a soon-to-be-released primer that will promote the inclusion of Latino perspectives in public discourse racial justice and systemic racism. In addition, in 2019, the organization released its first-ever document identifying and defining these terms and looking at just how many people identifying as Latino or Hispanic also identify as Black or Afro-Latino.

A Multi-Racial Awakening

For local social worker Esther Pereira, a former Broward County School Board member who identifies as Latinx with Black, White, and Indigenous heritage, organizing around BLM Alliance has helped her to channel her anger over racial injustice in her adoptive country as well as that which was commonly brushed under the rug in her native Brazil.

Her awakening came through her work in education and advocacy around DACA. She never imagined that a democracy as powerful as the United States could make it so hard for young people who came here as undocumented children to get a higher degree. The more she started organizing around issues like that, the more she came to reflect on how Brazilian society routinely jailed or killed people of color, the way she was now seeing in America.

“I want to say my entire life I was blinded,” she says, noting that she her family had benefitted from the stratification of lighter-skinned Brazilians, and with it the narrative that a person who was jailed or couldn’t get a job was in that position because they deserved it, and in Brazil, those people are often those considered to have a darker complexion.

In joining BLM Alliance Broward, she found herself connecting to the families of the victims of police brutality, connecting the dots of her work in education and immigration, and the more the marches grew, the more opportunities there were to educate the masses about civic engagement, especially about voting.

“It has definitely empowered Black and Latino folks, to educate them that they have the power in their hands to decide who’s going to be the state attorney, who’s going to be the sheriff, who’s going to represent,” she says.

And while she feels it’s important to vote for president, she feels that this country is so huge, it’s even more critical to vote down ballot.

“We have the power to change our local communities as we did in Broward with state attorney this past election,” Pereira adds, referencing the county’s historic election of its first Black State Attorney Harold Pryer.

A Collective Push

Pereira says she’s also proud to say that the public awareness strides BLM Alliance Broward has made have led to greater engagement from all sectors of South Florida society.

“We’ve got a lot of people coming to march for Black folks. We have the elderly, we have Hispanics, we have Jewish people, all coming to walk with us, to help organize, or sing or sell tee-shirts. It’s very empowering to see that we can all promote a change” Pereira says.

Anthropologist and community activist Laura Kallus is one White resident who has heeded the call to join in Black Lives Matter Alliance’s protests and other civic engagement activities.

“My whole professional life I’ve lived and worked in communities of color, but I did not take to the streets in protest until Trayvon Martin was killed,” says Kallus, who is the director of Florida’s largest free health program, Caridad Clinic in Boynton Beach, and the mother of two biracial boys.

“I took my older son to the Women’s March in Washington, DC. I listened as Black women turned away from the movement asking ‘where were all of you White women when our children were being gunned down in the street? Where is your rage for us?’ I made a vow to myself that I would always show up. As White women, we have failed our Black sisters. It’s time we all show up now, and we don’t stop showing up. So wherever there is a mother grieving the loss of her child to police brutality or racial injustice, my kids know that I’m going to show up. And I bring them too,, so they understand the world they are living in and how it’s important for all of us to fight to make that world better. It should not have to be your child to make you act or to make you care.”

Thanks to this collective push, concepts once considered audacious—like defunding the police—have entered into the discourse of all sorts of politicians at the local, state, and national level. But to keep the conversation going, you have to keep engaging at all levels, notes Walker’s fellow BLM Alliance organizer Lenisha Gibson, whose family hails from Bahamas.

“I think we can both remember a time when neither party would even mention Black Lives Matter as being part of a platform or statement,” says Gibson, a BLM Alliance Broward organizer who spent much of the winter working on voter education and engagement efforts in Georgia during the hotly contested runoffs for two Senate seats. For years, voter suppression had shut out diverse voices in Georgia’s elections. This year, however, was met with high voter turnout among communities of color, the result of years of organizing to push back against voter suppression.

“Being a Black woman in America, I’m thinking about my personal experiences and about what issues impact not just myself but also my community,” she says, noting that one of the best ways to get Americans thinking in an intersectional way is to start with their own identities and the issues that affect them, until they start to see where their lives relate to others.

“You can’t run away. You have to write letters, you have to vote, you have to do all of these things,” says fellow BLM Alliance organizer Michael Howsen, who identifies as a gay Black man with deep family ties to South Florida. “You also have to go out in the street and protest because that is the pressure that makes the, the writing and the phone calls. And all of those other things are real to the politicians and actually gets across that point that we really care about what’s happening. And we’re not going to allow you to pretend as though it’s not happening.”