Keeping Woke Culture Alive: Educators and Civil Rights Leader Talk About Their Efforts To Protect Black and Gender Studies in Florida’s Schools

In recent years, UnidosUS has been closely following a growing trend in some states to undermine efforts to create diverse and inclusive curricula. This past year, Florida became the epicenter of that controversy.

In March 2022, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law a bill that critics dubbed “Don’t Say Gay” because it bans Florida public school teachers from holding classroom instruction about sexual orientation or gender identity from kindergarten through third grade. In his victory speech following his reelection in November, DeSantis declared war on such curricula and programming by stating that Florida is where “woke culture goes to die.” Then in February, he banned a new Advanced Placement African American Studies course and announced plans to shut down public school system programs focused on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) and Critical Race Theory (CRT).

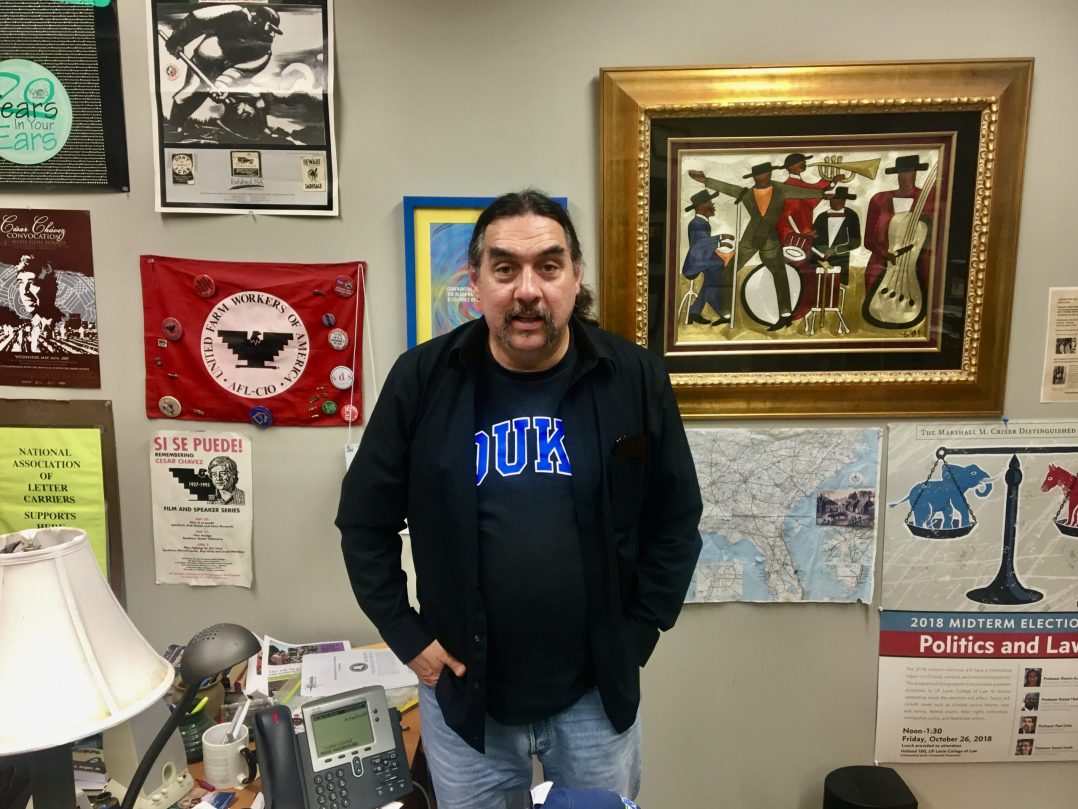

Concerned with how legislation like this uses the education system to foment a culture of fear and reinforce negative stereotypes about historically underserved and persecuted populations, on March 8, ProgressReport.co invited two Latinx Florida education leaders – University of Florida History Professor Dr. Paul Ortiz and South Florida youth rights and LGBTQ+ advocate Ayari Aguayo to participate in a podcast moderated by Dr. Vernon Damani Johnson, a community organizer, anti-racist trainer, and now retired political science professor in Washington State. The goal was to hear more about how civil rights-minded educators and students are reflecting on and responding to the “anti-woke” backlash.

PODCAST: Click here to listen to UnidosUS’s March 8 Teaching Tolerance Podcast featuring two diverse Latinx educators in Florida speaking with a veteran Black civil rights leader.

But since that recording, a number of bills with similar aims have quickly moved through the Florida legislature. In this post, ProgressReport.co provides a legislative update, as well as text highlights and additional context for the podcast itself.

On March 31, Florida’s HB1069, which expands on the prior Don’t Say Gay legislation, passed the State House. That bill creates a definition of “sex” that erases transgender, intersex, gender fluid, and non-binary/gender conforming people, thus requiring that school staff misgender their students by not allowing those students to choose their own gender pronouns. It also expands book banning by allowing anyone, not just parents, to file objections to classroom materials. Its counterpart, SB 1320, is still under review but has essentially the same language.

Meanwhile, Florida’s HB 999 seeks to dismantle DEI departments and initiatives in public colleges and universities by prohibiting institutions from expending any money that would advocate for DEI; promote or engage in related political or social activism; and include or espouse government speech or expressive activity of the Florida College System institution, state university or direct-support organizations speaking or acting on the Florida College System institution’s or state university’s behalf, “preferential treatment or special benefits to individuals on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability, or religion.” The bill also stipulates that general education must be taught through “a historical background and philosophical foundation” of Western Civilization while limiting funds for curricula that teach diversity or uses a racial lens, which would mean the removal of related majors and minors.

UnidosUS believes this bill can allow bad-faith actors to misconstrue an equity lens as “preferential treatment.”

Its counterpart in the Senate, SB266, does not ban majors like Women & Gender Studies but seeks to limit professors’ academic freedom by creating a post-tenure review. Its definition of discrimination is rooted in last year’s Florida’s anti-CRT bill HB 7. A hearing for SB266 will be held in the Appropriations Committee on Education on April 12.

Finally, HB 1421, also known as the “Trans Ban,” proposes to force minors who are currently using gender-affirming healthcare (such as hormone replacement therapy) to “detransition.” It also restricts access to care for trans adults, including denying them telehealth visits. Colloquially, it’s been called “The Trans Ban.”

Summarizing and Contextualizing UnidosUS’s March 8 Teaching Tolerance in Florida Podcast

Anti-LGBTQ+ Legislation

Podcast participant Ayari Aguayo identifies as Afro-Latina and a member of the LGBTQ+ community. She’s been advocating for human rights ever since she was a youth growing up on the U.S.-Mexico border learning about the role race, immigration status, and gender orientation play in U.S. politics and society. Since then, she has led efforts to advocate for gender-based human rights policies in Puerto Rico’s education and prison systems, and over the past five years, she has led a wide array of efforts to support empowerment programs for Black and Brown youth in South Florida. For example, she is currently a member of La Red de Mujeres Afrolatinoamericana, Afrocaribeña, y de la Diáspora, a group through which she can reflect on and advocate for LGBTQ+ youth of color impacted by the Don’t Say Gay legislation.

Even though federal anti-discrimination laws govern over this state law and lawsuits to that end have been filed, Aguayo says students and educators are still feeling the effect. For example, Aguayo says Florida school districts (who are you referring to when you say DeSantis and the rest of Florida) are discouraging students from stating the pronouns by which they want to be called in school. At the same time, Aguayo says the LGBTQ+ community is noticing that literature provided to educate schools about Title IX and human sexuality guides aimed at helping students who are openly gay or just coming out as LGBTQ+ are getting pulled from school campuses.

“If those guides are seen within the school system, the school board is asked to take them down. And we saw that with Broward County Public Schools because they had one, and Miami-Dade County Public schools as well,” Aguayo said during the podcast.

Over the past year, the National Education Association has been responding to the same concerns Aguayo is raising with publications explaining how federal law should theoretically protect against legislation like this. For example, last summer it published a three-page pamphlet titled What You Need to Know About Florida’s Don’t Say Gay Law which noted Title VII stipulates that a school district may not prohibit only LGBTQ+ educators from answering students’ questions about their families, may not prohibit recognition, and identity. Meanwhile, Title IX stipulates that schools cannot discriminate against students by prohibiting them from participating in sports or extracurricular activities or entering bathrooms consistent with students’ gender identity; schools cannot harass or permit others to harass students based on their gender identity, and that includes refusing to call them by their chosen gender pronouns; and protects students and educators from retaliation for complaining about such harassment and discrimination.

Before “Don’t Say Say” passed, Aguayo says LGBTQ+ advocacy groups met regularly with superintendents to ensure Title IX was being enforced, but she says this legislation is discouraging school leaders from doing so now.

“We are at pivotal moments of having to stand out for ourselves and our youth, right? Because we know that we’re being impacted, and it isn’t just in the school systems, it’s also medical care, making sure our mental health and wellbeing is there. Some of my community partners, their grants got pulled from the school systems themselves saying, ‘you cannot bring in therapists to provide free therapy for our young people, because that would be on the basis of race and gender orientation,’” Aguayo said in the podcast.

“What we’re seeing too is teachers that are absolutely terrified, teachers of all races, colors, religions, backgrounds, they’re terrified of what’s happening with their books, with their curricula. They’re having to take lists and inform the principals and superintendents what all that they are teaching. I myself do wonder what all can be said and shared,” she continued. “There is such censorship that when I come into the classroom or to do and lead any kind of workshop, I have to be mindful of what I say and don’t say, I’m not allowed to say directly say trans, but I can talk about diverse gender and orientation experiences, right? Language has become absolutely pivotal.”

Censoring Black Studies

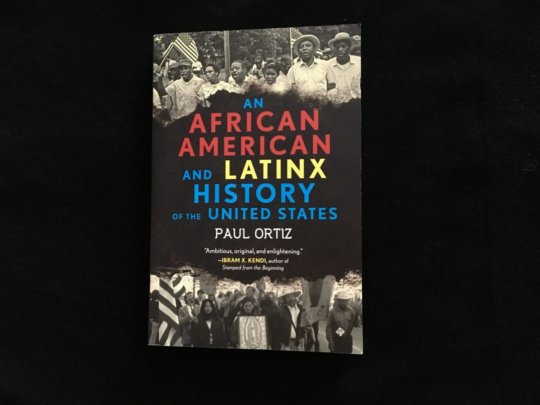

Podcast participant Dr. Paul Ortiz echoed Aguayo’s concerns about Florida’s crackdown on freedom of expression and identity politics. He grew up as a military child along the west coast of the United States and identifies as Chicano. Today, he is the director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at University of Florida in Gainesville, where he teaches history. He is widely known for his award-winning 2019 book An African American and Latinx History of the United States.

He says that while DeSantis’s Don’t Say Gay legislation was the first to pass under his rising campaign of anti-wokeness, the plan to chip away at studies sharing a more diverse view of history has been in the works for some time.

“What the state is trying to do is they’re trying to essentially create a situation where people do not have a history, a legacy tradition of struggle that they can draw upon,” Ortiz said in the podcast, noting that even before this latest ban on Black studies and announcement to do away with official DEI and CRT curricula, the state of Florida had already been censoring Black history books, especially those written by or about historic Black female influencers and changemakers. The state is prohibiting books that explain critical race theory or even provide dramatic interpretations of life during slavery from a Black perspective.

Ortiz says authorities seem especially keen on silencing the voices writers such as Kimberly Crenshaw, a co-creator of CRT and Bell Hooks, who developed the concept of oppositional gaze in feminist and Black media as resistance to white, patriarchal narratives, as well as Nobel-prize winning writer Toni Morrison whose novels chronicled Black experience in slavery and beyond.

“We learn these traditions through study. We can learn them through our elders through listening, but if you don’t have the privilege of being in, or growing up in a movement environment, you have to read these things, and the state understands this,” Ortiz said during the podcast, noting that in recent years, Florida’s institutions of higher learning have lost a lot of outstanding Asian and Black academics due to the racist sentiment.

Long before DeSantis called a war on woke culture, he was threatening to dismantle teachers unions, Ortiz added, although he sought to remind listeners the war on wokeness has merely been magnified by this latest governor.

“I don’t want us to get into the situation where we think, ‘oh, if we just get rid of Ron DeSantis somehow, then life will be rosy again. That’s not the case. It’s always been a struggle here,” Ortiz said.

Ortiz serves as president of the United Faculty of Florida, a member of the Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, and the largest of federation unions in the United States and leverages this role to remind educators of why unions matter.

“As long as the unions still stand in Florida, we have academic freedom articles in our collective bargaining agreements, so I teach Black studies, I teach Latinx studies, the state can say whatever it wants, but my collective bargaining agreement protects me from retaliation for doing the work,” Ortiz said.

He said some of his inspiration came from a white progressive high school teacher he had in the 1970s who encouraged students to cross from their working-class port town of Bremerton, Washington by ferry to Seattle to check out or buy books banned during that time.

In February, a Florida-based Black Lives Matter group called Dream Defenders organized a state-wide college and high school walk out in support of Black studies curricula, and they did so under the motto “Can’t Ban Us.” In solidarity with that effort, Ortiz’s program sponsored a three-hour Black Studies teach-in attended by more than 300 University of Florida’s students, faculty, and staff.

“As a historian, I was in movement heaven,” Ortiz said, noting that everyone came together to affirm an uncensored Black studies curriculum that should include the seminal works of Hooks and Crenshaw as well as Black feminist Angela Davis and Black and queer studies scholar Robert Ferguson. “I hadn‘t seen that such a turnout for a teach-in since like the second Gulf War in 2003.”

Aguayo said grassroots organizers in her own Afro-Latina and Latinx circles are drawing from the inspiration of all their past relations to do the same.

“We are making sure that our young people have the tools and access they need to be able to fight for themselves and to be able to learn this knowledge for themselves. We’re going back and learning from our ancestors like we did in this country back to 1776 through 1865, when we had to learn how to read and write ourselves,” Aguayo said. “We are equipping our young people to do the exact same thing. If you’re going to ban these books, we are going to find these books. We are going to distribute them at higher numbers.”

Call In Vs. Cancel Culture

Now in his 70s, panel moderator Dr. Vernon Johnson, has seen and participated in many movements of these kinds. His activism began in a quasi-underground organization called the All African People’s Revolutionary Party (AAPRP) in the early 1970s. During college and graduate school, he found himself studying and exploring social and political revolutions across parts of the continent that had only recently been decolonized, and in South Africa where Black and Brown or “Coloured” communities were defining their roles and their positions in a united fight against Apartheid. By the 1980s, he was writing his doctoral dissertation in political science at Washington State University.

After taking a position at Western Washington University in 1986, Dr. Johnson was on the state steering committee for Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition from 1988-92. When the white nationalist militia movement threatened the Pacific Northwest in the 1990s, he became a board member and president of the Northwest Coalition for Human Dignity. As one of few Black professors at Western Washington University, along the U.S. border with Canada, he found himself engaged in decades of inter-racial efforts to teach tolerance and anti-racism alongside Native, Asian, Latinx, and white community leaders.

Given this background, he was keen to learn more about how to improve solidarity across diverse groups of people in a way that leaves room for nuance and open dialogue.

In Los Angeles, for example, he noted that Latinos are as likely if not more to suffer police brutality, and sometimes negative sentiments about Black and Brown populations come from Latino leaders, as was the case with Los Angeles City Councilwoman who was forced to resign after making racist remarks about Black and Indigenous folks.

“Why do you think that the right is hammering away so much at this term, ‘woke’? Do you think that the term is still useful for defining a progressive cultural agenda?” He asked Aguayo.

Aguayo noted that even within the progressive community, or within historically underserved communities like the one broadly defined in the United States as Latino or Hispanic, “we’re still in the process of, we’re still processing what it means to be awake ourselves.”

She said that was especially true of Florida, where many Hispanics or Latinos identify as white or pass for white and thus enjoy less discrimination than those with more melanin. “I see a lot of that internalized racism, internalized misogyny when I am doing justice and movement building work.”

“What I’ve seen from friends, and from other leaders as well, is defining very specifically why and what happened with cancel culture that has folks be so afraid of being canceled, that now there’s an anti-woke movement,” she said. “It is key for us to call each other in rather than out, rather than cancel. And to really be mindful of what it means to have folks understand our full background history before going forward.”

Ortiz noted the backlash means he’s under increasing pressure to take his anti-racism and history workshops to communities in the north, rather than making waves in a state where many students are, in fact, Black and Latino.

“There’s no place in the world I’d rather be than the South Bronx, but you know, we should also be in Miami Dade, we should be in Osceola County, we should be in West Palm, and increasingly we’re being told you can’t be there with this scholarship,” he said, lamenting that sometimes he goes to talk to majority Cuban American students who may have heard of names such as Jose Martí and Antonio Maceo, but don’t realize these were people from their ancestral homeland who fought to end Spanish colonial rule.

“There are the things that the state of Florida doesn’t want you to know. They don’t want you to know how to organize, how to fight for democracy. The myth that Ron DeSantis is trying to push, and he’s been very clear about this is we were all created equal from the very beginning,” Ortiz said, “That’s a patent lie.”

Aguayo reaffirmed that “woke” movements thrive when they talk to each other so that they are better able to recognize collective oppression.

“When we look at our backgrounds and we look to see who is fighting and standing, we can learn from each other’s justice movements. We can learn from the rhythms, and we can also learn from the way that we’re being attacked because that is happening simultaneously.

Johnson hailed these insights and ideas for organizing in and outside of the public school system. “If enough of our kids are exposed to the kind of curriculum that people like yourselves are offering, I think they’ll be better off as citizens, and better prepared to deal with the challenges of the 21st Century,” he concluded.

–Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS consultant and the producer of the Teaching Tolerance podcast.