New York City’s District-Charter Partnerships Aim to Bring Innovative Teaching and Learning Full Circle

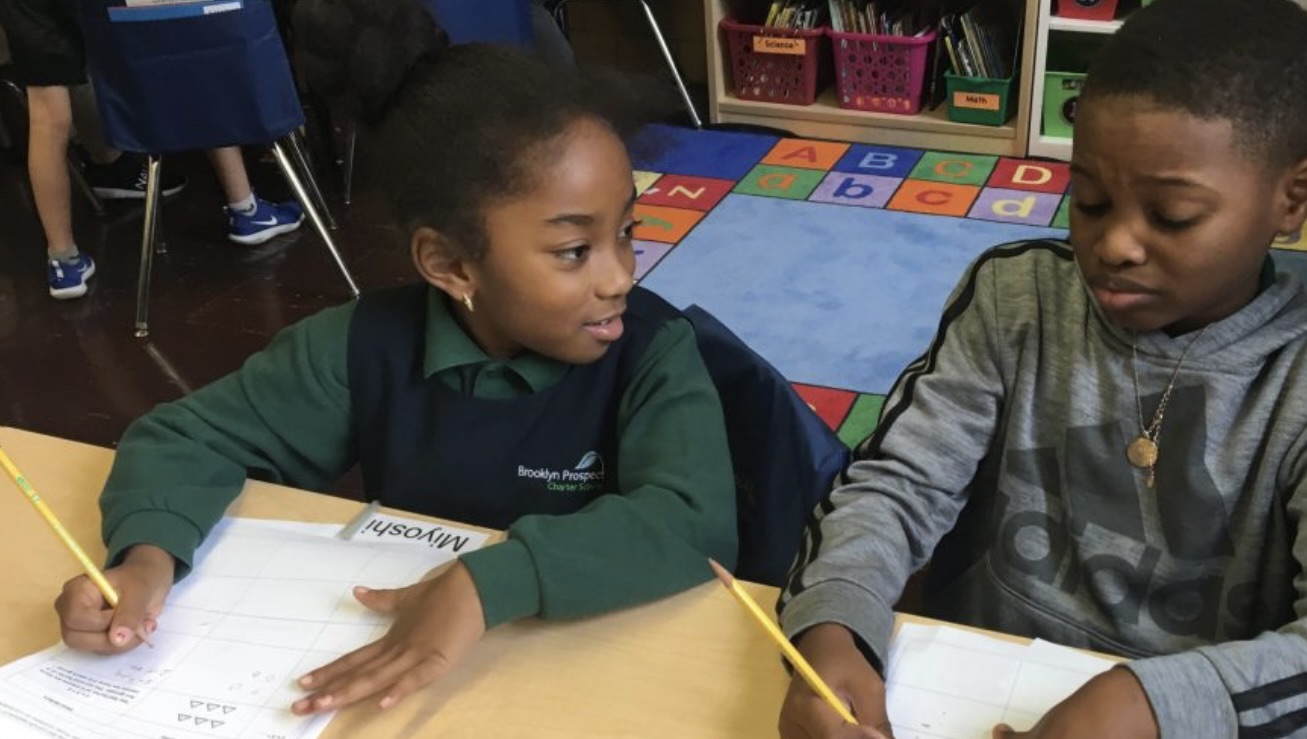

The fifth graders in a math lesson at Prospect Charter School in Brooklyn are a lively bunch, and that’s just the way the school likes it. First, they sit together on colorful floormats before a dry erase board, eagerly volunteering to answer story problems about things like their family’s groceries. There’s no harm in shouting out the wrong answer, because they’ll work together to find the right one. Then, students will pair up at tables using paper and pencils to further explore these math concepts in writing.

“Kids want to get the questions right. Maybe they don’t have the hard skills yet but they can still be successful,” says Prospect Charter Principal Jumaane Saunders, noting that he often tells the kids that math equals money.

The exercise was something Saunders and his staff adopted from ideas sharing with some public schools, and now he’s expanding on that spirit of collaboration and innovation through a citywide program known as the New York City Department of Education’s District-Charter Partnerships or DCP. DCP is comprised of two interschool partnerships – the District-Charter Collaborative (DCC) and Campus District-Charter Partnerships (Campus DCP) – and three professional learning partnerships with charter organizations – Uncommon Schools, Achievement First, and KIPP: NYC.

Founded in 2015, as one of Mayor de Blasio’s Excellence and Equity initiatives, the program aims to promote collaborative learning and the sharing of strong practices between all public schools, including charters and traditional district schools.

“New York City’s 20-year charter sector is customarily framed as a source of competition, and public battles with traditional district schools. But that’s not the city’s only answer for how charters fit into public education,” writes Century Foundation Fellow Conor P. Williams in an opinion piece for The 74, a nonprofit, non-partisan news site covering the American education system.

“Charter schools in New York City are like charter schools all over the country. They were supposed to be schools to test innovative practices,” says Melissa Harris, Chief Executive of the Office of School Design and Charter Partnerships. “The original thinking was that you test those practices in charter schools, and then you bring them to the district to be scaled.”

But the more traditional schools struggled to innovate amid budget cuts and bureaucracy the more charter schools began to pop up. This led to rather unfriendly conversations among school administrators and educators.

“You would have very contentious school closure hearings, and then those were coupled with opening new charter schools, so it kind of seeded this tension in the ground where people felt like ‘you have to close in order for me to open,’” says Harris. “And while folks still talked about innovation, it was no longer at the forefront of the conversations.”

How the District-Charter Partnerships Work

In 2015, Mayor Bill DeBlasio launched Equity and Excellence, which was aimed at raising the literacy bar by getting all second graders reading at grade level, ensuring that two-thirds of all students are college-ready by graduation, and reaching an 80% graduation rate. It also sought to provide universal access to Advanced Placement and college-track classes, computer science courses, and ensure all students take algebra by the ninth grade. And finally, it aimed to drive innovation through District-Charter Partnerships (DCP). One of the biggest partnerships is a school-to-school District-Charter Collaborative (DCC) in which groups of four schools—two district and two charter schools—meet regularly for two years to engage in a structured collaboration around various Learning Areas of Focus (LAF).

These school-to-school quads then work with a facilitator to share ideas on what’s working and what isn’t to ensure all children in their classrooms are getting a quality education. Then, they take those ideas and attempt to implement them through inter-visitations of one school by all the participants of that group. There are 1,700 public schools in New York City, and so far, 94 of them representing all five of the city’s boroughs have participated in the program.

Debunking the Myths

Before participating teachers can share ideas, they must first break down the stereotypes they have of each other’s schools.

“Charter and district schools very rarely have the opportunity to come together and sit at the same table and work towards the same goal, and that’s exactly what DCP provided,” says Alejandra Palomino, a fifth grade math teacher at the UnidosUS Affiliate Amber Charter School in East Harlem. She participated in the partnership to try a math curriculum provided by the New York City Mathematics Project, sponsored by Lehman College.

“The first conversation we ever had was called ‘peeling back the onion.’ We all put our assumptions out there on the charter and district systems. We were honest and blunt. You know, charters get paid more, district teachers can never get fired, and from there we started to build that trust,” adds Palomino, noting that educators quickly realized they were facing a lot of the same issues.

Saunders, on the other hand, said his upbringing in both the public and private school system, and his work teaching in public, charter, and private schools across the country, helped him to think more critically about the pedagogy he wanted to share with the DCP. The child of Caribbean immigrants who didn’t have much to start out on, he grew up in Brownsville, one of the most economically challenged parts of Brooklyn.

“I was not very tuned in with the American way of doing things. I didn’t fit in, so they placed me in the lowest-level classes,” he says. But then in the sixth grade, he got an opportunity to attend a private school for predominately wealthy families.

“It just shocked me how quickly I learned that my classmates there weren’t smarter or more intellectual than my classmates at the public school. It was really about opportunity and how the teachers framed what was happening,” Saunders says.

That question would inspire him to teach public school in California with a bachelor’s in biology, and then obtain a master’s in education where he could look at various education models. He later moved back to New York City to teach and work in school administration, and that’s where he came to recognize that the bureaucracy of traditional district schools can hinder innovation.

“I started to really believe that charters were actually not about the privatization of education but more about really being in a space to explore ideas and see what’s happening,” he says.

These instructors echo what New York City School Chancellor Richard Carranza said about charter schools during the UnidosUS Annual Conference in San Diego last August.

“You can’t be a leader in any large urban system and not have to deal with the question that happens around charter schools. I mean, the minute I got into New York, that was the very first question I was asked,” the veteran educator told a packed audience during a workshop on closing the K-12 achievement gap for children of color.

He said District-Charter Partnership helped the DOE and teachers union leaders come together to break old paradigms and dig deeper into public education concepts that serve all children.

“I am a super fan of good schools—good, affirming school—and I see examples in both the traditional and charter world,” Carranza told the audience. But he said the only way both schools work well is when they’re truly working together to share innovative practices. He also noted that he himself was the product of the U.S. public education system and that he was very much against privatization of the U.S. education system. “I will tell you the very families that we serve are the ones that never get served well, and they become a commodity.”

The Innovation

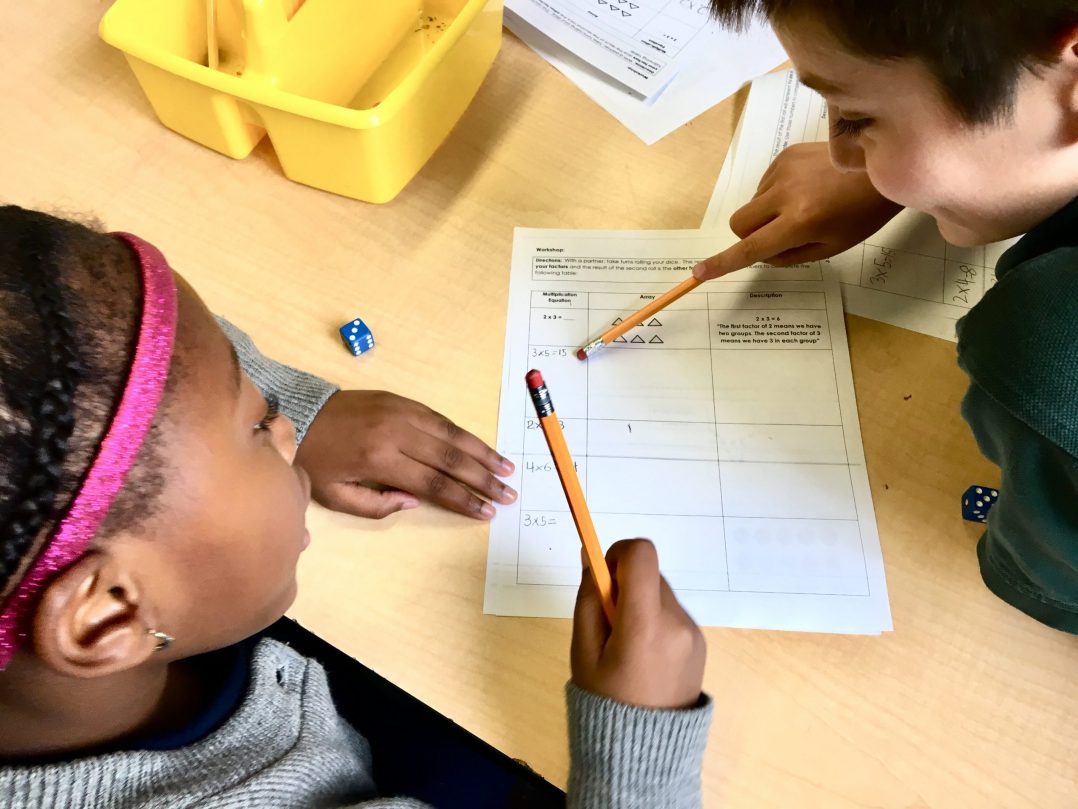

For Saunders, that instructional innovation in areas like math is key to his students’ success. The DCC’s two-year math program provides schools with a more culturally flexible and inclusive math curriculum, a coach, and assessments for tracking performance. In fact, he’s now experimenting with another math program called Opportunities to Respond, which helps math teachers offer more guided support for their English learners (ELs)

During this school year, the DCC’s focus areas include specially-designed instruction for individual and multilingual learners; using restorative justice practices to improve communication and resolve conflicts; promoting literacy across all content areas; bolstering parent and community engagement; and increasing opportunities for education in science, technology, engineering, art, and math (STEAM) by providing more career and technical education and culturally responsive math instruction.

“Other districts have focused on structures like common application and enrollments systems– ways for the district and the charter sectors to work together more efficiently,” says Paul Byrne, Senior Director of District-Charter Partnerships for New York City Department of Education’s Office of School Design and Charter Partnerships. “We’ve taken a different path by really focusing on the instruction that is happening in our classrooms and the leadership that is happening in our schools.”

For Dawn Brooks DeCosta, principal of the traditional district school Thurgood Marshall Academy Lower School, the program has helped her give and take ideas for social and emotional learning. From the charter schools, she was able to pull ideas on building regular school assemblies to motivate and rally students together, and on posting pictures of the students in the entryway to the building to remind them they are noticed, counted, and appreciated.

“We’re always trying to find ways to have them love something about the day, to look forward to something so they can persevere—like through a math lesson,” Brooks DeCosta says.

Students at Thurgood Marshall Academy Lower School practice yoga. Photo courtesy of Thurgood Marshall Academy Lower School.On the flip side, her own school has shared lots of ideas for helping mitigate stress, especially among students with tough socio-economic circumstances. Many of the students in her school are poor or even homeless, and some are also dealing with domestic or neighborhood violence. To help them feel grounded and in control, the students are trained to teach each other yoga and meditation. They’ve also replaced regular class “rules” with their own “charter agreements” for how they want to be treated in the classroom.

“We turned it over to the students to lead,” she says. “It’s like how do you want to feel instead of simply what not to do,” she says.

Finding Results

Byrne says that District-Charter Partnerships have created opportunities for teachers and school leaders to learn from and with each other across sector lines through two facilitated programs that bring educators into each other’s schools to exchange ideas and instructional practices, collaborate, and offer feedback.

While district and charter schools are seeing promising results from their participation in District-Charter Partnerships, it’s still too early to draw definitive conclusions about impact based on student data. But administrators and educators within the program have spoken consistently of improved practices and increased effectiveness.

“We can say that our schools that have been focusing on the math instruction are seeing increases in their student achievement. Our schools that are focusing on restorative justice practices are changing their discipline practices,” says Byrne. Districts that have partnered with Uncommon Schools and the Relay Graduate School of Education have made some of the largest gains in English Language Arts scores across the city last year. “We have teachers consistently and overwhelmingly tell us that they feel more confident in the instructional practices that they’re engaging with and learning about, and that they feel better equipped to teach their students on a day-to-day basis.”

Well-Rounded Students Benefit Us All

At UnidosUS’s other Affiliate Amber Charter Schools located in Kingsbridge in the Bronx, that same confidence seems to be evident among the 800 diverse kindergarten to fifth-grade students they serve. All students receive Spanish at least once a week beginning in kindergarten, hoping that by the time they leave, they feel comfortable defending themselves in Spanish. They also receive a well-balanced curriculum utilizing the same robust group-think instruction for reading and math found through those partnerships, as well as classes in art and music.

“Music is a universal language. It’s not just a good beat that we’re dancing to, but there’s purpose and meaning behind it,” explains Amber Charter School Chief Academic Officer Sashemani Elliott. “It’s really about exposure so that when the kids leave school, yes they learn reading, they learn math, but they also know the world is bigger than Kingsbridge and bigger than East Harlem.”

Amber Charter Schools are convinced that the ability to know a multitude of words, numbers, people, and ways of doing things will make these students better problem solvers, more engaged citizens, and more insightful and caring professionals.

“At the end of the day, when we’re laying down on a hospital bed and we need help, nobody’s going to look up and say ‘are they a doctor from a charter school or did they come from a DOE school?’ It just doesn’t matter. It’s about good people and good learning. That’s what we’re in the business of doing,” says Elliott.

As a civil rights group working to ensure that all children in the United States have equal access to a high-quality education, UnidosUS welcomes the information gleaned and lessons learned from these types of partnerships.

“We recognize that all public schools must do more to ensure that all students, English Learners, and Latinx students are meeting their full potential and are prepared for college and career. Everyone benefits when we work together to close the achievement gaps that persist in the education system,” UnidosUS President and CEO Janet Murguia tweeted earlier this year.