Marking International Women’s Day with Reflections from UnidosUS’s Educational Godmothers

All across the world, women and girls are celebrating today, International Women’s Day, as a day to celebrate women’s historic achievements and raise awareness about what it means to identify as female. As a result, it’s quite common to explore themes related to motherhood, but what about godmotherhood? Serving as a proxy parent or a role model and mentor can have a major impact on the lives of all kinds of people, especially up-and-coming leaders of color.

With this in mind, last fall, UnidosUS’s National Institute for Latino School Leaders (NILSL) decided to raise the profile and expand the reach of Latina educational leaders by developing the Las Madrinas Senior Advisory Council. The goal was to help participants of NILSL’s cohort in California, a state with an enormous Latino population, advocate for student rights at the local, state and federal level. In celebration of International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month, which runs through March, four of the six women involved in the council caught up with ProgresssReport.co to offer some reflections on their roles. They discussed what got them interested in leading educational initiatives, what advances they’ve made, and what challenges lie ahead, all while acknowledging and celebrating historic Latina figures who inform and inspire their work.

“The term madrina is the Spanish word for godmother,” notes Dr. Feliza Ortiz-Licon, UnidosUS’s Principal of Education Programs. As UnidosUS launched the inaugural NILSL California cohort, it was important to convene a group of education experts with deep knowledge of the education landscape, policy-making process, Latino students, and English learners (ELs).”

One of the Madrinas’s central roles is to help NILSL fellows in the state of California to advocate for the implementation of the new English Learner Roadmap. This statewide policy and education tool provides guidance to local education agencies on how best to support ELs. To do this, they are participating in panels and hosting webinars about lessons they learned in the field, as well as sharing advice and knowledge as thought leaders in cultural competency.

“It’s filling a mentorship void that many education leaders of color experience when navigating the educational ecosystem,” Ortiz-Licon explains. And given the many logistical challenges of the pandemic, they’re also helping this cohort get creative about how to organize, advocate, and simply be present when in-person contact is so limited. Ultimately, they’re there to serve as role models who are available to talk and reflect as fellows forge their own educational career paths.

The Madrina They Wished They Had

“I did not have the advantage of a mentor showing me the ropes and guiding me through the career maze. I learned the hard way, by trial and error, through observation and by developing a network of persons who are experts and professionals in my field,” says NILSL-CA Madrina Martha Zaragoza-Díaz, who now runs the educational lobbying firm Zaragoza-Diaz & Associates.

“As a lobbyist representing non-profit organizations who advocate for ELs and their families and who promote bilingualism/multilingualism (California Association for Bilingual Education [CABE] and Californians Together [CatLog]), I believe I have provided educational leadership in the development of educational policy that serves our ELs and their teachers in a positive manner,” she adds.

In collaboration with the Boards of CABE and CalTog as well as partnering organizations such as Ed Trust West, UnidosUS, and California Association of Bilingual Educators, her firm has contributed to the development of the English Language Development Standards, California Spanish Assessment, the State Seal of Biliteracy, and the passage of Proposition 58 of 2016, a piece of legislation that led to the elimination of the controversial 1998 law known as Prop 227. That law prohibited any form of multilingual learning in the classroom. The repeal of Prop 227 also cleared the path for the development of the English Learner Roadmap., She and her associates also helped secure funding for the establishment of the Bilingual Teacher Professional Development Program and statewide implementation of the EL Roadmap.

Zaragoza-Díaz says she’s especially excited to mentor young Latinx women to ensure they gain the political clout they deserve for the leadership roles they so often play in the Latino or Hispanic community.

“It just seems to be part of my DNA,” she says.

Through participation on panels and webinars, she often shares her “do’s and don’ts,” of lobbying, a list of items she’s had to adjust to fit the current pandemic.

“Working in a virtual setting has been challenging because there isn’t that personal connection,” she says, noting there are no handshakes, hugs, or cups of coffee to offer. Plus, it’s harder to read someone’s body language or facial expressions when they’re not in your physical space. She also says it’s easier for someone to dodge commitment to the position on a bill you are requesting. As such, she tells her mentees that constant online, phone, and social media contact is key.

“Even if it is to say hello, you have to maintain your presence,” she says.

For Hilda Madonado, superintendent of the Santa Barbara Unified School District, losing the in-person connection has been a challenge and an opportunity.

“The pandemic has obliterated the societal structures that define our way of being – our families, freedom, and social convenings to name a few,” she says.

She and her staff have had to work on a complete redesign on the delivery of instructions to students.

“In education, the lecture or sit-and-get model is no longer the way to teach,” she says. “The instructional materials available to replace this model have for the most part not been designed to replace it. Poor or no internet access has exacerbated the opportunity gap for some families. Lack of language supports and outreach to families at home have also been impacted by the pandemic.”

But Maldonado has been able to share some of those concerns and pedagogical adjustments by participating in national education webinars and mentoring study groups engaged in research and capstone projects.

“My hope is that by sharing my own learning from my success and my challenges, I can mentor others to take this work to higher levels of the policy, practice, and personalization needed for students,” she says. “I believe a child is not defined by where they come from but rather by who they are, and our work should be to help them achieve their talents and dreams even if it’s in more than one language and culture.”

But Maldonado says one of her other big concerns is that today’s intense political climate has many families and educators living with fear and a “pervading lack of hope,” two things she considers contrary to a good education.

Madrina Delia Pompa, a senior fellow for education policy at the Migration Policy Institute’s National Center on Immigration Integration Policy, echoes these concerns.

But for her, the technological challenge is one that will be met more easily than the challenge of defining and addressing equity in an increasingly diverse society with diminishing budgets and growing cultural isolationism.

“These challenges are very real to NILSL Fellows in their professional lives. It is critical that the Fellows understand how to make policy work in the cause of equity in this complex context,” Pompa says. “The idea of working with colleagues at a different stage in their career than mine is professionally and personally invigorating. While I have advice to give, I find that I learn as much or more from their perspectives and values.”

She has been able to do exactly that by reviewing NILSL Fellow’s policy memos, which are their final capstone for the program.

Dr. Rosita Ramirez, National Director of Constituency Services for the National Association of Latino Elected & Appointed Officials (NALEO), considers her Madrina role as “additional technical assistance, and an extension of the work we do with NALEO members.”

The two fellows that she mentors are heading up charter and district schools. This collaboration can be key to a school system educating a predominantly Latinx student population. And yet, it often lacks the supports and services needed to properly meet those students’ academic and language needs, regardless of a school’s governance structure.

The pandemic and subsequent school closures have exacerbated the state’s already existing inequalities that make it challenging for school districts to address the instructional, mental, and physical needs of their diverse students. But California is also home to the nation’s largest share of ELs, who make up 20% of the state’s total public-school enrollment, and these are often among the students suffering the most, explains Ramirez.

“In light of this reality, my work equipping Latino school boards of with the most current data, policy developments, and best practices for supporting school districts, families, and the students they represent is more critical than ever,” says Ramirez.

Taking Inspiration from Latina Women’s History

And while the Madrinas seek to be the godmothering mentors most didn’t formally have in their own careers, they certainly can speak to the ways they take inspiration from historic Latina figures.

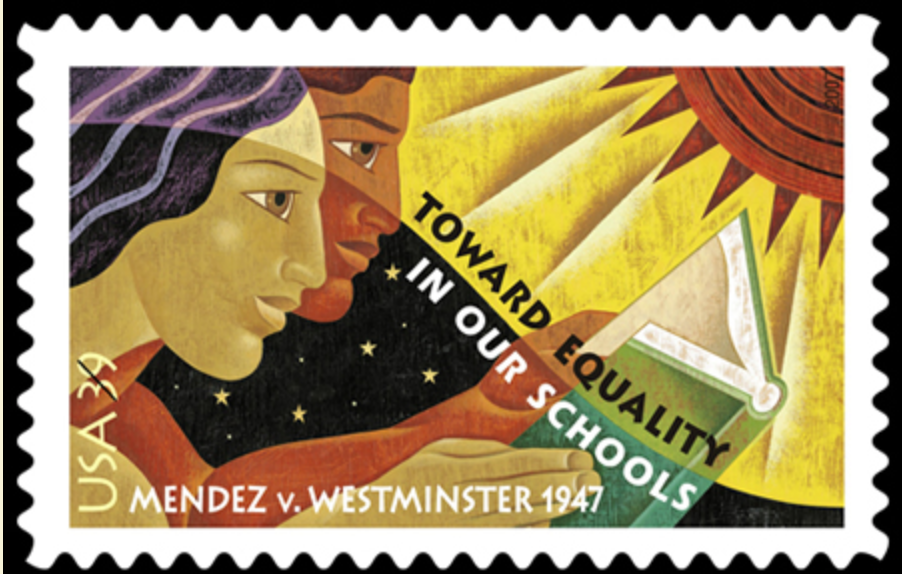

Zaragoza-Díaz and Maldonado both mentioned historic California public student Sylvia Mendez as one of their heroes. In 1943, Mendez, then an elementary school girl, was enrolled with her brothers and cousins in a segregated Hispanic-only school. Her father decided that he wanted his children and nephews enrolled in the White school because it had better resources. But the school only accepted children that looked most White, and denied Mendez entry because of her dark complexion and Latino surname.

Her parents and other families in the same situation filed a class-action lawsuit that became known as Mendez v. Westminster, and in 1947, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Mendez, marking the first time a U.S. court found segregation unconstitutional. Within the year, California schools were desegregated, although it would take until another landmark case, Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954, for the U.S. Supreme Court to abolish formal school segregation.

“In spite of all of that adversity, Sylvia knew she had to succeed after her parents fought for her to attend school. She became a registered nurse and retired after working in her field for30 years,” says Zaragoza-Díaz.

Mendez now lives in Fullerton California and gives lectures on the historic contributions made by her parents and the co-plaintiffs to the desegregation effort in the United States. In 2011, President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“Sylvia Mendez, her mom, and her aunt had the courage to stand up to an educational system that clearly was racist. They give me hope to continue to seek the truth and speak it,” adds Maldonado.

Maldonado also named Guatemalan Mayan human rights activist Rigoberta Menchu as a source of strength and inspiration in these politically tense times. Menchu is best known for having spoken out about genocide of indigenous peoples by sharing how this heinous crime claimed the lives of members of her own community and family.

“She influences my work because she did for herself what no one else was willing to do for her. She saw an injustice and didn’t let it persist, I hope to do the same,” Maldonado says.

And finally, she says Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street, is another writer who helped her gain inspiration for giving testimony about the Latino experience because her books made Maldonado “feel seen and understood.”

Ramirez says her greatest role models were Latina academics.

“When I read Dr. Guadalupe Valdes’s book, Con Respeto: Bridging the Distances Between Culturally Diverse Families and Schools: An Ethnographic Portrait, and Dr. Patricia Gandara’s book, Forbidden Language: English Learners and Restrictive Language Policies, I felt as though I had finally identified kindred spirits who had written about an experience that was so close to my own,” she says. “In essence, these women became advocates for students like me, paving a roadmap for my dissertation studies. In addition to providing a framework for my work and that of others like me, they have spent their lives mentoring other advocates who are now working, much like NILSL-CA fellows, to support the next generation of students in California’s educational system.”

Pompa is one Madrina who did have a strong role model and advisor in her midst. Gloria Zamora, a Latina pioneer in the field of bilingual learning, administration, and advocacy, mentored her from college through herearly yearsas a teacher trainer.

“Her example of tenacious activism for ELs, whether in establishing NABE or testifying before Congress, created a path for my work. And to this day, I think about her quiet, but fierce, approach when I encounter barriers to an excellent education for all children,” says Pompa.

But Pompa and her fellow Madrinas all say they are also the products of the legacy of the thousands of women who previously made inroads in fields such as politics and education.

“I added to the history,” says Pompa. “In education, I have been fortunate to have lived through changes that were essential to improving the lives of Latinos and immigrants. My role is to help secure those changes in an evolving society.”