Cuban-American Artist and Educator Lili Dominguez Cast Her Vote in Favor of Social Inclusion, the Environment, and Creative Civic Engagement

Dominguez never did get that tube of paint, but she did manage to slip her hand out before getting in trouble. And during the three months she dealt with a swelling arm from the incident, she figured out how to mix the dried-up old paints students had outside the cupboard into any number of hues. Today, the Miami-based artist and educator is not only a master colorist, she’s a visionary in helping diverse students and teachers harness their creativity for learning in less than optimal circumstances.

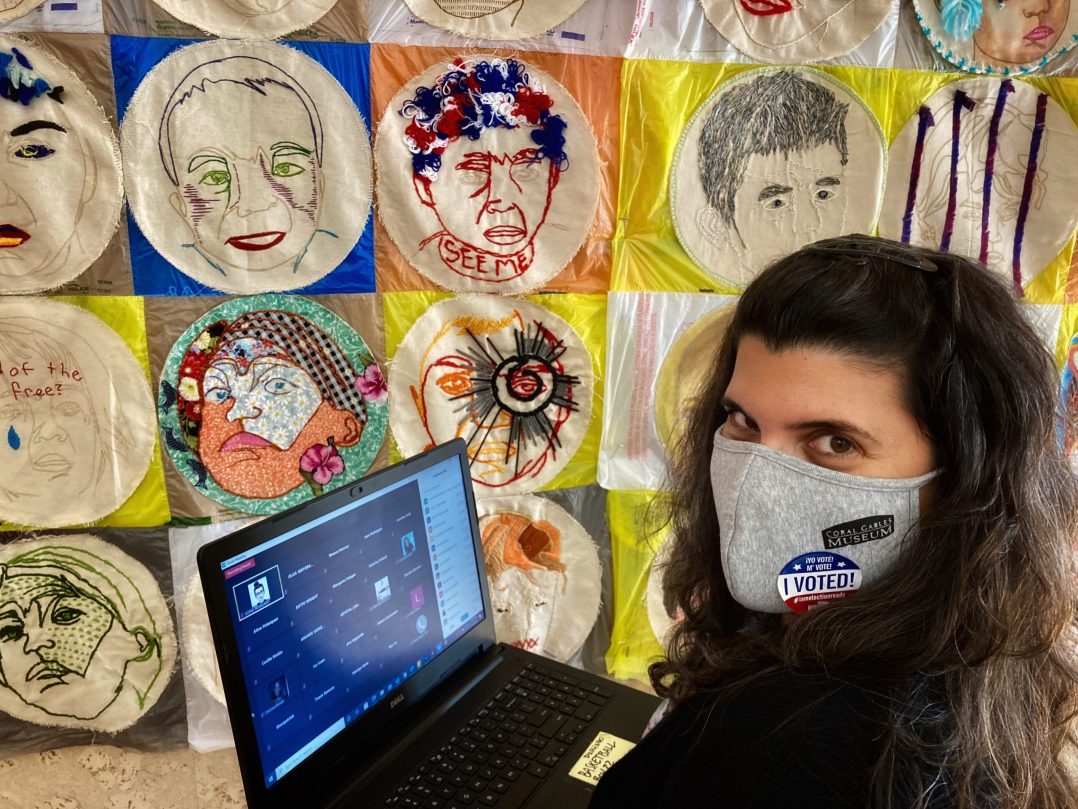

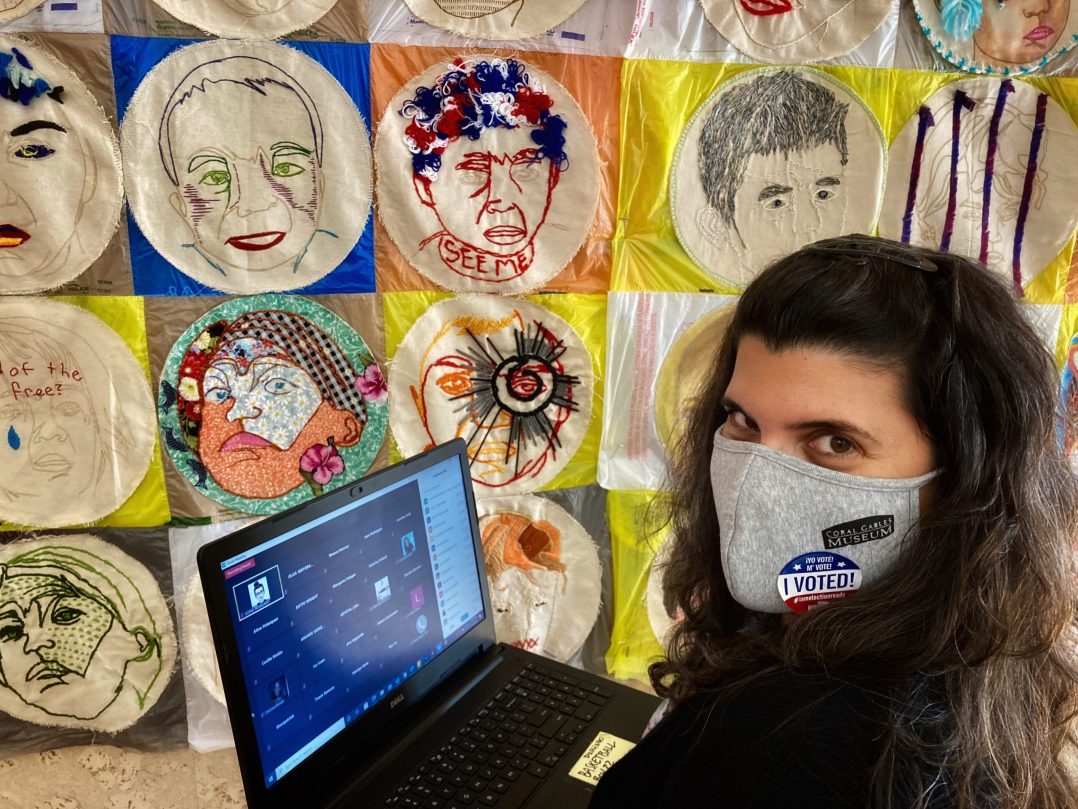

Armed with a master’s of fine arts from the University of Miami and a doctorate in teaching from Barry University, she has spent years building multidisciplinary curriculums for South Florida’s K-12 schools and institutions of higher education. In addition to her work as an adjunct teacher of everything from art to life skills to adult and continuing education, and in multiple school settings, she recently took a job as director of education at South Florida’s Coral Gables Museum, which is dedicated to civic arts. In that role, she has to integrate art, science, nature, social inclusion, and civic engagement, online and outdoors.

Sure, it’s a massive challenge holding all these roles, raising a 10-year-old son, and navigating the pandemic in a coronavirus hot spot, but through it all, she says she wants her diverse students to harness “the value of precariousness.”

“When I’m teaching things like color and a kid says ‘Oh, I don’t have part of that color,’ I ask them, ‘Okay, well how can you make it?’ Precariousness brings you to do what you can with what you have.”

Dominguez says she voted in favor of greater public resources for civil rights and the environment in the November elections, and she fights every day to maintain and grow resources for engaging education during the current health and economic crisis. But she wants those resources to help students and educators, especially those coming from complex life circumstances, to fuel an assets-based approach to learning.

That can be a hard sell in a place like South Florida where not all immigrants, especially those from Cuba, look at their past with so much nuance.

“Because I teach humanities, I can ask them to tap into those stories,” she says, explaining how this broad topic lends itself to educators asking students to talk about their origins, and stories about those origins that helped to shape them. Some are excited and proud to share, others don’t want to remember their past at all, and others may even feel ashamed of their struggles, especially if they suspect their peers may have certain social or class biases.

Unlike many older Cuban emigres, Dominguez never had or lost material wealth on the island. She was poor and yet she grew up in a coveted bubble of creativity. In fact, some Cubans would say it shielded her from taking to the streets to the streets to protest for greater economic and social freedoms, or simply flee the confines of communism.

“I was doing what I wanted to do. I was painting, drawing, making friends at school. We were very competitive and we were trying to get into exhibitions to present our work. I was very active, and I was expressing myself through the arts,” she says.

Her parents could see her talents and appreciated the joy it brought her. Still, as they braced for a never-ending series of financial barriers on an island where money runs thin and international trade barriers limit shipments of just about everything, including basic household goods, they couldn’t imagine turning down an opportunity to migrate to Miami.

“They saw it as this tremendous tragedy, and so boom, everything got cut off because my mom and my grandmother— the only two family members I had in Cuba at the time— all got their permits approved,” she says, referring to visas they received through the U.S. government’s visa lottery program. “It was either me staying behind or one of them staying behind with me. I didn’t want that to happen.”

Faced with this choice, she packed her bags and migrated to South Florida, where she took English classes and found a job working at a department store. Not all immigrants are fortunate enough to come with the legal protections historically afforded most Cubans thanks to a contentious six-decade Cold War history between our country and theirs. Still, it took her a bit to find her way. Even in the 1990s, many immigration advocates and institutions of higher education weren’t giving out clear guidelines on how to get foreign degrees accredited, but eventually she began picking up coursework in printmaking and photography and tried her hand as a freelancer in visual journalism.

In fact, she decided to dedicate her master’s in photography to the craft of teaching her skill, and she enjoyed that so much she went on to earn a doctorate in teaching while she worked as an adjunct educator in schools across South Florida.

Her focus on the arts has helped her deepen the critical thinking and problem solving skills of students and fellow educators by encouraging them to get resourceful and build things with their hands. That might mean relying on whatever materials they have at their disposal. It might mean encouraging them to go out into their yards or neighborhoods to search for debris that could be recycled, or aspects of nature— a native plant, an invasive iguana— to document through pictures or drawings. She’s even been able to do that during the pandemic.

For example, through partnerships she’s developed between the Coral Gables Museum and local, state, and federal agencies, she’s been able to invite small numbers of teachers out into places like the Everglades National Park. Once there, they might go exploring a swamp or some old-growth trees looking for some unique species like the Florida Tree Snail (Liguus fasciatus), whose shell patterns are unique to the hammock where they dwell, an art they’ve been crafting for thousands of years. Then they’re tasked with creating a related art piece they can share with their students in a regular or virtual classroom.

And while she likes to take students on fieldtrips, for now, she’s Zooming science, history, and art lessons right out of the museum, sometimes even using an exhibit housed inside. She’s also working to organize outdoor activities on the museum grounds, which can be especially inviting for urban youth who might not have access to a yard or a park. But all the while, she encourages her students to observe their surroundings, to scavenge for clues that could help them better identify social or environmental problems in their communities.

Afterall, these are the ways she says she learned to leverage community engagement and support in her own childhood.

“I used to go around asking people ‘Do you have some paper? What about paint? Do you have any projects? Maybe we can barter,” she says.

That spirit of cooperation helped her transition into a diversifying Miami, one where she might be attending classes with Salvadorans, Ecuadorians, and Haitians, to name just a few backgrounds. And while she has always been intrigued by the concept of sharing personal stories, she admits it takes some practice to gauge how best to do so from one class to another.

“It’s not like the idea of a TedX talk where you just show up and say, ‘Hey! I’m Cuban! Where are you from? Let’s exchange stories!” She says. “Some of them are reluctant to do that. You have to take different approaches – like through visual expression or artistic expression because sometimes what they could share comes after they’ve created something.”

But getting them to a place where they can swap those stories helps them think about what makes her experience, or those of the students, similar or different to their own, which is just how she moves them into other academic courses, such as life skills or civic engagement.

Take, for example, presentations on voter education ahead of this month’s 2020 elections. It’s not her place to tell people what or who to vote for, but she can certainly explain the process of registering and researching concerns on the ballot. Then she says she’ll get students talking about themselves and their larger communities by asking “What issues are important to you? What issues aren’t? If an issue doesn’t affect you, does it mean it isn’t a problem? Why is it important to think about how it affects other people?”

Whatever the outcome of this historically tense U.S. election, Dominguez says she’ll always forge way to inspire creativity and community through innovative teaching practices.

“Whatever the outcome of the election, I’ll be here continuing to collaborate on creative projects that focus on giving a voice to those who are silenced or don’t feel represented in society, so that their issues are equally visible to everyone,” says Dominguez.

You don’t have to live in South Florida to join the civc arts programs Lili Dominguez creates for students and educators. Visit Coral Gables Museum for all virtual events.