Engaging Students in Discussions of Border Issues Can Be Uncomfortable But Constructive if it’s Conducted with Strategic Social, Emotional, and Legal Planning

U.S. Vice President’s Kamala Harris’s recent warning to Central Americans not to migrate to the United States has left many educators wondering how to lead a student discussion on migration, welcome migrant children into their classrooms and youth centers, and train others to do the same.

“I want to be clear to folks in this region who are thinking about making the dangerous trek to the United States-Mexico border: Do not come. Do not come,” she said, during a June tour of Central America, during a tour of Central America that was to examine the region’s intense struggles with poverty, violence, climate change, and political corruption.

Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez quickly fired back from Washington, noting that it is not illegal to seek asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“People come because their life or their livelihood is under threat. They come reacting to circumstances they did not create,” notes Latina author, educator, and immigrant worker rights advocate Alejandra Domenzain.

Domenzain, who left her role as an adult education program director at UnidosUS in 1999 to work in the field of immigrant labor rights in Los Angeles, is quick to point out that U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War era contributed to the very challenges it now pledges to help change in a long-term development plan. The idea is that with such plans, people won’t feel forced to migrate, but results could be years in the making, if they ever actually come to fruition.

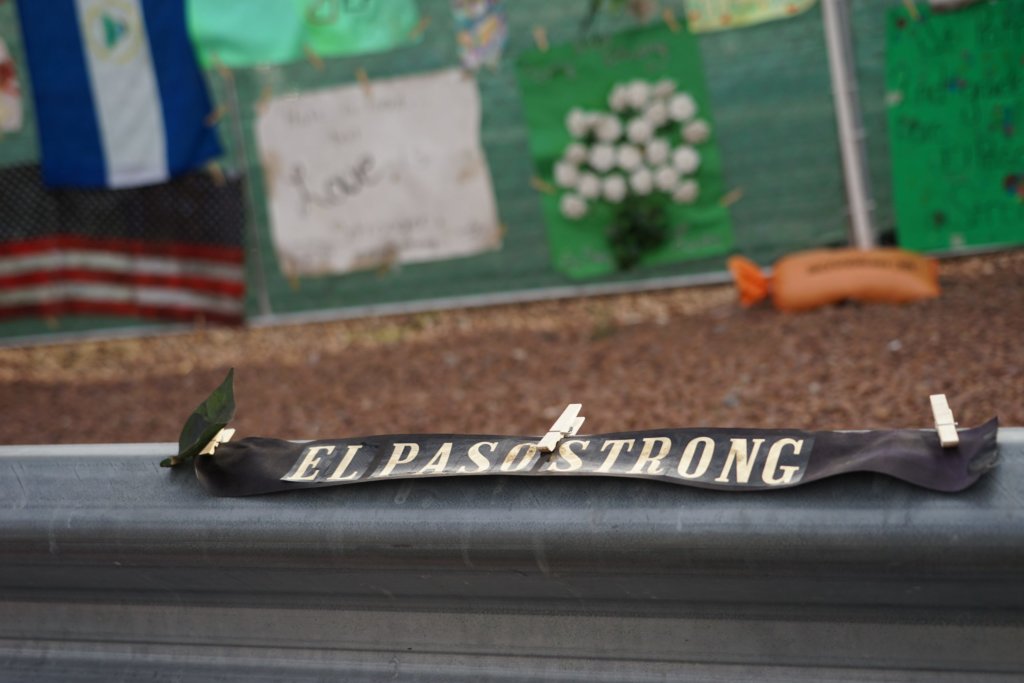

“The house is burning and you’re telling people, don’t leave,” says Domenzain. With that in mind, on Monday she’s releasing her first children’s book titled For All/Para Todos, which centers on a young girl and her father who cross the border because they can no longer make a living by farming and are unwilling to do unsafe factory jobs.

“This is based on the reality that U.S. trade deals made it difficult for farmers to compete with the heavily subsidized and mechanized U.S. agrobusiness, and also that U.S. “maquilas” or assembly plants offer low wage and often dangerous working conditions,” Domenzain explains.

Domenzain wrote the book in English and Spanish, with translation support from Irene Prieto de Coogan and illustrations by artist Katherine Loh. At the end, it includes background information about the issues and discussion questions that teachers can use to guide discussions. Her promotional materials also include a PDF of some of her favorite resources for teaching about immigration.

Other questions that may arise from the vice president’s comments might have generated as their own parents were watching the news at home:

- Why do people migrate?

- If migrating is a human right, why are there so many legal obstacles to doing it?

- What role did U.S. political and economic policies play in creating conditions forcing people to leave in the past few decades? What role are they playing now?

- How long might it take the United States to help Central America improve its socio-economic and political outlook so that people feel less pressured to migrate?

- How does the U.S. benefit from immigrant labor? Are immigrant workers offered safe, fair working conditions?

- What about Americans migrating to Central America because they can’t afford retirement in their own country?

Domenzain and others say asking students about current events can be a great way of getting their classes thinking about the world and their place in it. Written in verse, the book begins with a life in a place that sounds an awful lot like Mexico and Central America:

One day her dad said, “Flor, we’re leaving our land.

The fields have all turned into dust and dry sand.

We cannot grow corn with so little water.

Our land cannot feed us, my dear darling daughter.”

“Can’t you find other work? Get a job in the factory?”

“I’ve tried,” said her dad, “It was unsatisfactory.

The machines and the chemicals fill me with fear,

At work mom got sick after only a year!

I couldn’t save her but can save you my dear.

You’re all that I have, and I can’t raise you here.”

The starting point for the book establishes empathy, so that students who are immigrants and those who are not can connect with the situation. Then it moves into making that migrant child an agent of consciousness raising and social change. The young girl, Flor, begins to understand that the father faces an impossible situation: put up with injustice or risk losing everything he’s worked for:

“You can’t get more money or work without pain;

You’ll get into trouble if you dare to complain.

If you do, guards will come, in no time at all,

We can have you locked up and removed with one call.”

On the other hand, Flor faces the anger and frustration of not being given a path to belonging even though she is proud and loyal to her new home:

“If you were born here, then you belong

If you do not, you’ll always be wrong.

Our grandparents weren’t born here, yes, that is true,

But we must draw the line, and we draw it at you.”

In an ideal world, any classroom discussion on immigration should harness news stories and testimonials that bring all students and educators to want to engage from where they’re at, says Margarita Machado-Casas, a professor of bilingual education at University of California San Diego. She crossed the border into the United States as a child after she and her family fled economic and political strife in Nicaragua.

“It’s about action and advocating, seeing their role as educators, but also as advocates for the kids who are on the border, who are eventually going to end up in our classrooms,” she adds.

Machado-Casas obtained her doctorate in education at University of North Carolina in the early 2000s, just as that state’s population was seeing the nation’s largest growth in Latinos. She went on to teach students of and faculty of education at University of Texas San Antonio, and today at UC San Diego to do exactly that. She had the unique opportunity to work with students living in border regions, some of whom had experienced migration first–hand, and together, they would take academic groups to volunteer in child migrant detention centers in the United States and to a center for asylum seekers in Mexico. In so doing, she helped her students and fellow professors consider what aspects of an immigrant story could inspire change or also trigger the trauma associated with migration.

Preparing the Discussion, Notifying Parents

Machado-Casas welcomes the same strategies Domenzain is now promoting with her book and list of educational resources, and she has many thoughts on how to prepare for those classroom projects. For example, she says it’s important to notify parents ahead of presenting a curriculum on migration.

“At the end of the day, schools are government officials, at least that’s how many migrants see them Machado-Casas says, noting that as such, she recommends getting to know families first. That starts with ensuring teachers and administrators know that civil rights laws protect students and their families from being forced to share information on their legal status. The landmark 1982 Supreme Court Case Plyer vs. Doe for example bars states from denying students a free public education on account of their immigration status, and in fact, sharing that status against the family’s will could cause a school to lose its federal funding.

But just by getting to know the families and letting them share what’s comfortable, educators can develop greater understanding of the structural problems that lead people to migrate without a guarantee of legal entry. It can also help them gauge which families are fearful about talking, and which might be ready to share their stories. Those who emigrated some time ago or have since obtained some form of legal immigration status might be more engaging and able to speak on behalf of other parents.

From Education to Action

Following these consultations, educators can decide on the best ways to engage the students alongside a book reading, a film or video clip, or a testimony. Is this a safe enough space for students to have a live discussion or would it be better to have them write an essay? Could the students become pen pals with children in migrant detention centers or write welcome letters to those detained children who might soon be released?

Yes, says Machado-Casas, and some immigrant advocacy organizations can facilitate these activities, but it’s important to keep the correspondence light.

“The letter could be around your experiences at school, what you do in your grade and what your day looks like, and they can ask the migrant student what their school was like back home,” she says, but deeper conversations should wait, so that children in detention or even in the classroom don’t feel legally or emotionally exposed.

To ensure this, she encourages educators to work with school administrators and facilitating organizations to respect cultural emotional concerns and avoid legal landmines.

But writing letters to migrant children is just one of many ways educators can teach students about civic engagement as students, as global citizens, and even as future vocational pursuits. With the right research and consultation, students and their families could also organize welcoming parties for new migrant families, join demonstrations, and find creative ways of giving migrant students the space to share whatever aspects of their life and culture they see fit. Plus, even students who aren’t old enough to vote can share these stories and experiences through letters to elected officials or with adult members of their families who can vote or join immigrant advocacy campaigns.

“The idea of solidarity with immigrant families is just as important within the classroom, as it is among the faculty in the school,” says Machado-Casas. “Everyone should be learning about what’s happening, about who’s out there doing the work, and what roles we all can play as advocates.”

This can also take place in an intersectional way, such as in the process of helping to support English learners (ELs). For example, an EL might be encouraged to teach other students words from their own native language, and to do so in a way that makes them feel proud and empowered by the culture they came from. In so doing, the student builds rapport from an assets-based perspective, and then the sharing of those harder immigrant experiences can create greater understanding, empathy, and action.

UnidosUS Director of Parent and Community Engagement Jose Rodriguez is an expert in parent engagement and bilingual/EL education, and he too supports these strategies.

“It is important that parents of recent immigrates and even the foster families of unaccompanied minors be included in the decision-making process pertaining to their education,” Rodriguez adds.

Domenzain scheduled her book launch on Monday to coincide with this week’s ninth anniversary of DACA, or the Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals, a law that allows people who were brought to the United States as undocumented children to stay here and study. It is presented in partnership with the Los Angeles Public Library and Skylight Books and will have several guest speakers. Those will include a representative of United We Dream, one of the first organizations to coin these students as DREAMers and push for the DACA legislation, and a a young DACA recipient who is now an immigration reform leader and an educator who has been active with the labor and climate justice committee of the California Federation of Teachers.

“Not only are immigrants making contributions to our economy by their labor and contributions to things like social security and taxes, but they are also actually the ones that are pushing us, inviting us, forcing us to live up to that promise of justice for all,” says Domenzain.