The Gates Foundation Chats with UnidosUS Affiliate Leader Gini Pupo-Walker, the First Latina to Serve on a Tennessee School Board

This blog first appeared on Medium. Author Allan Golston is President of the U.S. program of Progress Report’s funder, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Follow him on Twitter @AllanGolston.

One of the things I love most about my job is that I get to regularly meet inspiring educators, school leaders, advocates and other professionals working to expand opportunities for students across the country. These conversations not only inform my own work, but they also feed the spirit, because I get to learn about who they are as people — why they were drawn to education and what forces motivated and influenced them along the way.

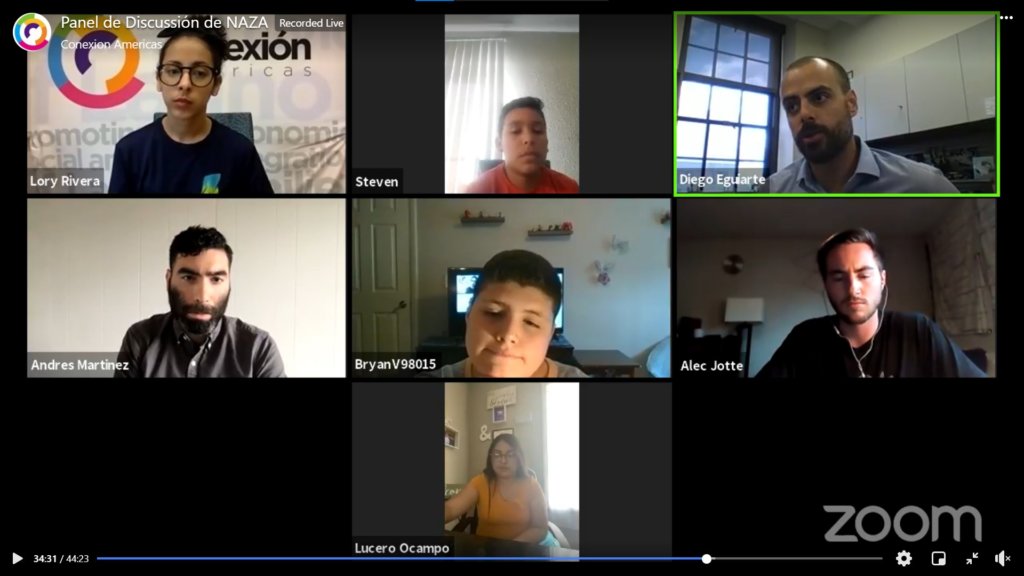

One of the education leaders I’ve been inspired by recently is Gini Pupo-Walker, the senior director of education policy and programs at Conexión Américas in Tennessee. Conexión Américas (a Gates Foundation grantee) is a non-profit organization working to help low- and moderate-income Latino families realize their aspirations for a better quality of life in Tennessee. The organization also leads the Tennessee Educational Equity Coalition, which includes 65 organizations and over 1,800 members in the state.

Gini’s background is impressive and inspiring. She has been a classroom teacher, an education policy leader, and a strong advocate for her community. And last August, she made history by becoming the first Latino or Latina ever elected to serve on a school board in the state of Tennessee, winning a seat on Nashville’s District 8 board.

I had the chance to connect with Gini and talk about her background, her perspective on the progress Tennessee students have made in recent years, and how she’s planning to make the adjustment from advocate to decision-maker in her new role. Below is a snapshot, edited for length and clarity, of our conversation, which happened to take place during Hispanic Heritage Month (something we talked about).

Allan: Let’s start at the beginning. How did you start your career in education? What motivated you to pursue that path?

Gini Pupo-Walker: I grew up in Nashville. My dad is Cuban, and my mom is from rural Tennessee, so that varied my childhood culturally. I always knew I wanted to be a teacher from very early age. I wasn’t sure what that path would look like, but I knew it would happen. I went to Indiana University, and I was so drawn to history and philosophy and political science that I decided to major in history and worry about the teaching part later.

I ended up getting a master’s degree in Spanish, and then I got certified to teach here in Nashville and actually ended up moving to Seattle and started my teaching career there — at West Seattle High School for five years. I eventually made it back here about 15 years ago and started teaching in the public school system and evolved from the classroom to the district leadership level and now working for a non-profit in education advocacy.

If you would’ve asked me 20 years ago if I would be doing what I’m doing now, I would never have imagined it, but it’s been the right fit for me.

Allan: And, so, after many years as an educator and advocate, you decided to run for school board in Nashville. What made you decide to run? It’s certainly a tough job in any district. How does it feel to now be in the role of “decision-maker”?

Gini: I left our public school system a little over three years ago, and a lot of people assumed I was doing it to run for school board. But it was one of those things where other people may see you as a potential candidate or elected official, but you don’t see yourself that way. When I left the district, I began working in advocacy. So, I was encouraging people to run for school board, teaching people how to speak before school boards, and teaching people how to advocate. And the more training I did, the more I really saw what tangible power lies in that policy-maker role.

When I was working in the school system, I was selected for the National Institute of Latino School Leaders, which is a UnidosUS program that I know the Gates Foundation funds. It was a turning point for me. I began to see my role as an educator and advocate differently and developed my own skills connecting my personal story and experience with policy. I was asked to speak to legislators on a number of issues, and it was an amazing opportunity.

So, fast-forward a few years and I see this board position opening. And I have a lot of young Latino staff here, and when the incumbent in my district decided not to run, they literally had a sort of intervention and said, “We really want you to run. You should do it.” It was the district I grew up in, where we have family and a lot of history, so, it was a tremendous opportunity.

Allan: I love the way you talk about finding your voice, because that’s what leaders do. They figure out what their voice is, and then figure out how to use that voice and platforms for the benefit of others — whether that’s an organization, private or public. And I’m a firm believer that we need more people of color in education and to hear their voices. Better representation can help transform the system and help it perform better.

So now you are the first-ever Latino school board member in the state of Tennessee. How do you feel about that distinction and what are you most excited about in this new role?

Gini: Well, I think I’m fortunate to have multiple perspectives to bring to this role. During the campaign, I wrote a blog post about what it means to be a Latino as a candidate. As a person, my consciousness and identity as a Latina has evolved over time. When I was young, the word “Latino” didn’t even exist. It wasn’t until I became a teacher and students saw me representing them — especially when I was in Seattle, where I was the only bilingual teacher, or staff member, frankly — that my thinking evolved and their issues have become part of my identity throughout my career.

People see me in different ways. I spent time as a community school organizer, so some see me as a social services-type advocate. Others see me as a teacher advocate. Others see me as a parent advocate, because I’ve done parent engagement. I have all these hats, and I could speak at length about those hats, but I will say that I took the responsibility of running as a Latino for the board very seriously.

Twenty-six percent of our students are Latino. One percent of our teachers are Latino in Nashville. There’s just not enough people who can advocate for those students, who understand them, can welcome their family, and so on. I am getting calls already from everyone from cafeteria workers, to students, to parents who’ve gotten my number. These are all Latinos who say, “we need somebody to help us.” And within the bounds of being a board member, I want to make sure people feel like there is a way for their voices to be heard.

Allan: I know personally, as an African-American, that it can be tricky to hold all of the different roles — either the roles you take on yourself or those that people bestow on you — and over time and in my own journey I’ve had to find my own comfort zone. People will try to put you in different boxes, but I hear you saying and am inspired by how you don’t have to be in a box. You can both serve the Latino community and serve all students.

Gini: Yes. On the campaign trail, the way I put it was to say that I think the aspirations of immigrant parents are the exact same aspirations as the wealthiest parents in my district. They’re the same aspirations for their children. There’s no distinction for me.

Allan: Exactly.

Research shows that Tennessee has become a national leader in student achievement growth over the past several years. So, it’s at once a kind of bright spot with significant progress to be proud of, but there are also stark realities that show how schools and systems in the state are not serving students of color the way they need to. How do you square the two realities? And what do you think have been the drivers of the state’s overall success?

Gini: We’ve had governors and leaders that have shown amazing, bipartisan leadership. We had Democratic and Republican governors who have really kept their foot on the gas on education. That’s been really important. It was also important that we had truth in advertising — being honest about how our students are actually doing. We had a big hiccup along the way, but we were able to raise our standards significantly, create an aligned assessment, and all of that really matters in getting teachers and others thinking differently about instruction and rigor and the role of teachers.

I think the other piece was the teacher evaluation system that was instituted, which really changed the conversation. It empowered school leaders to be instructional leaders, and I think that really changed the culture in schools and while I was working in schools, you could really feel it.

I think all of that matters. We have some issues right now with our assessment, no question about it, but I think overall the state takes tremendous pride in what we’ve accomplished to date. The reason I joined Conexión Américas, where I work now, and we started a state-wide coalition was because we are still leaving far too many students behind, and the numbers are pretty stark. So, we’re working to lift all boats, but students of color and English learners are not catching up fast enough.

The education commissioner and her team have been incredibly receptive on this issue. Our state’s plan under ESSA (the Every Student Succeeds Act) is considered one of the best among states, and is centered on equity, and I think our organizing work deserves some credit for that.

Allan: You’re absolutely right. Having a number of advocacy groups at the table — particularly when big decisions are being discussed around things like state-wide plans — is so critical. Steady, consistent leadership that can carry a bipartisan vision is also pretty special and unique. It’s hard to push for and achieve excellence in an inconsistent environment.

Shifting focus for a minute, I’m the executive sponsor for the Latinos in Philanthropy group here at the foundation, which is a resource group of all of our Latino employees. It’s been an honor for me to serve in this role. We, as others across the country, are celebrating National Hispanic Heritage Month, and I wondered what it means from your perspective to be celebrating this month and reflecting on the success of the Hispanic community and the challenges the community still faces today?

Gini: Well, as a teacher I always took the opportunity to use the month to highlight all kinds of things, but in the organization where I work now, we look at it as a really important opportunity to press forward a story about the identity of the Latino community and what we contribute and what we bring to the table. It’s also really an important time to highlight unsung heroes in our community. People are doing really hard work every day without fanfare to improve the quality of life for Latinos, particularly in Nashville.

But I’ve always had a little trouble with things like Cinco de Mayo and celebrations like that, because I feel like it trivializes our culture a bit. So, for me, I always look at this month as an opportunity to celebrate the intellect, hard work, and contributions of the community. It’s about making sure we tell the stories about hard work and contributions — whether those contributions are coming from a family has been here for five generations or if they only recently arrived in this country. I will say that it’s more important than ever given the particular rhetoric in our country today around immigrants and what they offer or are not offering in their local communities.

I think it’s also an opportunity to help people understand the complexity of this community and that people can be from many different cultures. Some people speak Spanish, some don’t. Sometimes their parents spoke the language, but they don’t speak it. There are many different ways you can show up as Latino in this community, which is a very different community than, say, a Miami or Los Angeles or Washington, D.C.

Allan: That’s such an important point — that races and cultures have complexity and richness and aren’t monolithic. We should be celebrating that richness, because it’s a key part of our own national story.

There’s another point I wanted to touch on…you mentioned “truth in advertising” earlier and I know Tennessee has had challenges with its statewide assessment, TNReady. What is your take on the assessment and how it fits into a broader picture of how Tennessee’s students are doing?

Gini: It’s something Conexión Américas has been involved in locally. Many parents — particularly African American and Latino parents — are feeling like their kids are being left behind, passed on grade-by-grade without advancing academically and they want to know where their kids stand in terms of learning and also what to do about it. I feel strongly that we need a rigorous assessment that is tied to the instruction that students are supposed to be getting, and that that information must inform all kinds of decisions. I’ve been getting pushback on that, and I will get pushback as a board member on that.

I’m worried about where we are in Tennessee on this issue. I think it’s more important than ever to continue to talk about these assessments and what they mean…what they mean for students, what they mean for communities, what they mean for schools. Frankly, parents need to have that information.

Many parents use that information to buy their house. They decide where they want to live based on the quality of the neighborhood schools. Why shouldn’t all families have that information and be able to use it?

Allan: It’s certainly an interesting issue. Standardized assessments will never tell the full story of how a student is doing — that’s why we look at other measures like grades and in-classroom work and have conversations with teachers — but it’s certainly a piece of the larger puzzle. Parents, as well as non-parents who want to know how students in the state are doing, would likely want that information.

Gini: Yes, at Conexión Américas, our philosophy is not about making change at the school or district level. Our philosophy puts the student and the parent at the center.

Allan: We should all put students at the center, that’s a way of expressing that value.

Gini, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me. I’m excited about the work you’re doing and look forward to seeing how you’ll continue to drive impact and performance in schools and in your community. What you’re doing is inspiring and it absolutely made my day. Thank you for inspiring me and others with your story.