Texas can do more to ensure students recover from pandemic learning loss

We take a look at what we learned from the 2020–21 school year assessments and what districts and the state of Texas are doing to support learning recovery.

By Roxanne Garza, Senior Policy Advisor | Kendall Evans, Policy Analyst, UnidosUS

Spring is in full swing, and so is testing season, the time when students across the United States take statewide assessments as a measure of academic learning. In this blog, we take a look at what we learned from the 2020–21 school year assessments (2019–20 assessments were cancelled at the beginning of the pandemic), and what districts and the state of Texas are doing to support learning recovery for students most impacted by the pandemic. In Texas, where Latinos account for 53% (roughly 2.8 million) of the public-school student population, Latino students experienced steep declines in math and reading achievement, as measured by the statewide standardized assessment—the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR).

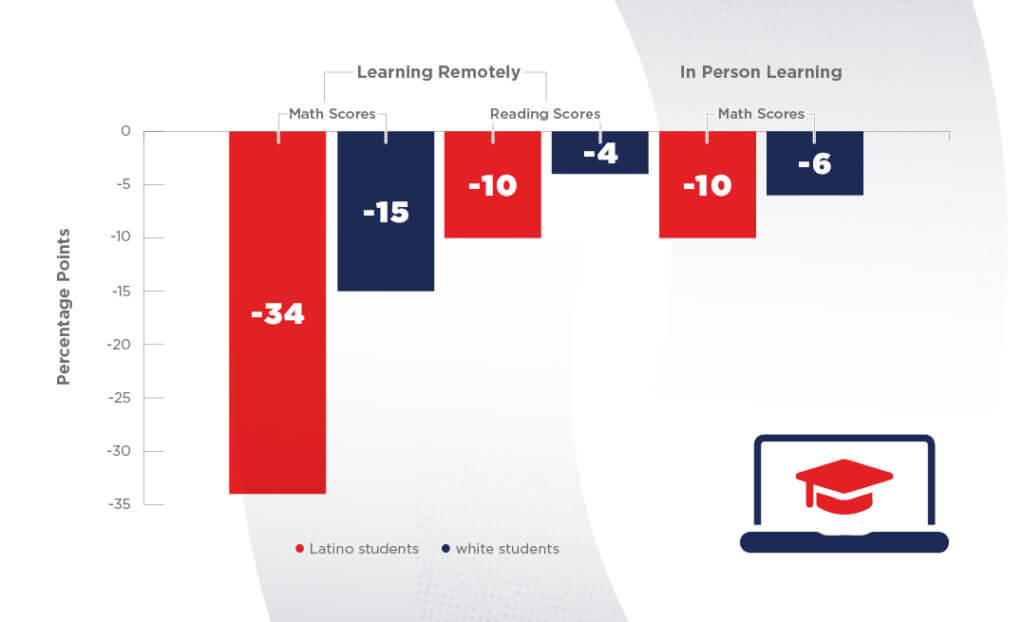

While fewer students took assessments in 2021 than in 2019 (87% compared to 96% respectively), standardized test scores fell across the board, with disproportionate impacts on students of color, low-income students, and students learning remotely. Pandemic-related disruptions and challenges brought the percentage of students meeting grade-level expectations on the STAAR test down overall, by four percentage points in reading and 15 percentage points in math, compared to 2019, but the test results demonstrate large differences by districts’ instructional modality, with steeper drops experienced in districts with more students learning remotely. For example, in districts where 25% or less of students were learning in person, the number of students who met math test expectations dropped by 32 percentage points, and the number of students who met reading expectations dropped by nine percentage points. When compared to districts where more than 75% of students were learning in person, the drop was nine percentage points in math and one percentage point in reading.

The most acute declines were experienced by Latino students in districts with over 75% of students learning remotely—Latinos experienced a 10-percentage point decrease in the number of students meeting reading expectations and a 34-percentage point decrease in those meeting math expectations, compared to their white peers (-4% in reading and -15% in math). When looking at districts where students were primarily learning in person, Latino students lost roughly twice as much ground (-10%) in math as their white (-6%) and Asian peers (-5%).

Compounding these effects is the fact that Latinos also make up the largest share of students identified as economically disadvantaged and at-risk (75% and 67%, respectively)(Students identified as at risk of dropping out of school are under age 26 and meet one or more specified criteria, including not advancing from one grade level to the next for one or more school years, being pregnant or a parent, or being a student of limited English proficiency). Students from low-income backgrounds lost twice as much ground as their more affluent peers across instructional modes (-6% vs. -3% in reading and -20% vs. -9% in math).

There are also 1.1 million students identified as English learners (ELs) in Texas and 88% are Latino. English learners in grades three through eight who took the STAAR assessment in 2021 also experienced declines compared to 2019—50% of ELs did not meet proficiency in reading compared to 44% in 2019 and 53% did not meet proficiency in math compared to 26% in 2019.

Now Texas is taking important steps to remedy the interrupted instruction and associated decrease in student achievement. Most notably, the state has implemented a new law (effective 2021), House Bill 4545, which requires school districts to provide all students who do not perform proficiently on the state’s reading and math assessments with an accelerated learning plan (e.g., pairing the student with a highly effective teacher or providing the student with at least 30 hours of accelerated instruction, such as summer school or after-school tutoring in the subjects in which they are struggling). In addition, the law requires districts to use STAAR data to identify struggling students and develop accelerated learning plans to help students in the areas they need most help.

While the use of federal funding by local education agencies can play a large role in supporting the implementation of the law, it is unclear how each district will specifically use the funding to adopt the mitigating measures set out in HB 4545.

Districts are also making plans for how they will use federal ESSER funds provided by the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund that provides school districts with emergency funds to address the impact of COVID-19 on schools—for their pandemic recovery. The San Antonio Independent School District has stated that it will use $22 million of the $12.4 billion allocated to Texas in ESSER funds, to add 30 noncompulsory days of classes to the school year. The funds will pay the full hourly rate for staff who choose to work the additional days and the costs of operating schools. Fort Worth ISD also plans to spend $45 million of the $261.5 million allocated to the district to create more time for learning. The district will also invest $7.6 million for structured literacy and enhanced math for students who are in the 15th to 25th percentile on the NWEA Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) Growth test.

Additionally, Fort Worth ISD has plans to create Freshmen Success Teams at all high schools, where new coaches will work on implementing strategies for increasing the percentage of students who are on track to graduate. This innovative approach can go a long way in preparing Latino students for high school graduation and supporting their transition to postsecondary education. The state of Texas experienced a 4.2% decline in college enrollment since 2019, driven mostly by the decline in enrollment at two-year institutions, where Latinos are overrepresented. Community colleges experienced a nearly 11% drop in enrollment during the pandemic, a larger drop in enrollment compared to four-year institutions. This trend was especially notable among Latino students (a 7.7% decline in public two-year enrollment compared to a 0.9% decline in four-year enrollment between 2019 and 2020).

The Texas Education Agency has a plan for evaluating its interventions. According to the state’s plan for American Rescue Plan ESSER funds, the state will evaluate the evidence-based interventions it included in its plan in short-, medium-, and long-term cycles through ongoing stakeholder engagement, diagnosis of student mastery including data from state summative assessments, and, where applicable, third-party evaluation.

While some districts have laid out their plans to allocate millions of dollars in ESSER funding to accelerated learning strategies such as adding days to the school year or extending the schools day to close learning gaps and create more time for learning, there is more the state of Texas and its districts can do to ensure that students most impacted by the pandemic have their needs met. Namely, states and districts should set aside funding for English learners, who have experienced disproportionate adverse impacts as a result of distance learning in both language development and academic learning; closely track and monitor funds to ensure that funds are being equitably allocated; and fill teacher shortages, especially those with TESOL qualifications.

Districts should also work to meaningfully engage linguistically and culturally diverse families and communities—including students, families, educators, service providers, community members, and advocates—to build more inclusive and equitable systems than those that existed before COVID-19. Students should also be provided with socio-emotional, mental, and physical health support. All students deserve to learn in an environment where they receive support needed to learn, develop, and thrive. That means considering the specific needs of English learners, so that the impact of the additional challenges their communities have faced is mitigated and does not further impede their learning. School districts should also address foundational challenges to support English learners, including addressing the lack of consistent and high-quality data about individual students and the supports they are provided, as well as the shortage of diverse educators in many places.