Q&A: University of Florida Professor Maria Coady Shares the State’s Historic Dual-Language Education and Best Practices for National Bilingual/Multilingual Learner Advocacy Month.

In 1988, Florida amended its Constitution to make English the official language, and today, civil rights advocates grow around supports for English learners (ELs), who make up 10% of the state’s K-12 population. Even some Latino policymakers argue that they managed to struggle through total English immersion in school while growing up in Spanish speaking homes. But last year, Maria Coady, a professor of ESOL and bilingual education at University of Florida, published a book showing that this was not always the case. In fact, during the early 1960s, Florida was at the forefront of cutting edge bilingual education that helped young Cuban children fleeing their home country’s revolution by providing academic instruction in English and in Spanish. The ‘cutting edge’ nature of the program was that native English speakers were provided the same opportunity to learn content through two languages.

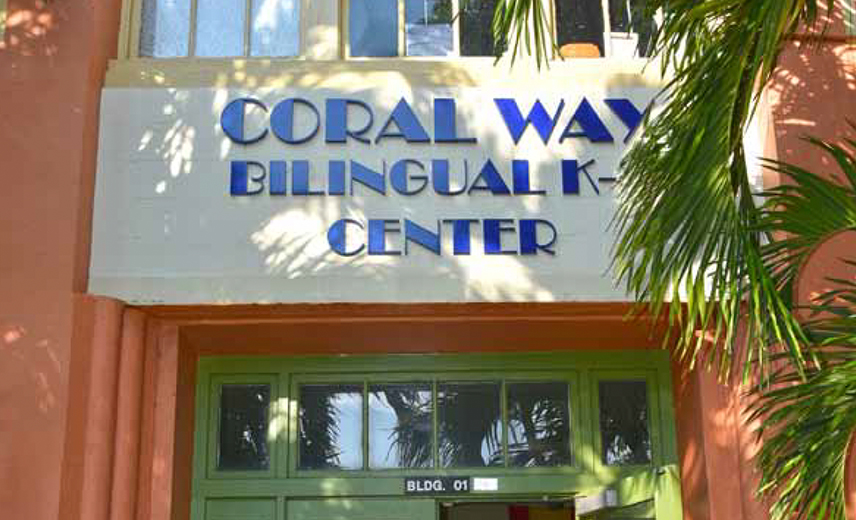

The book, titled The Coral Way Bilingual Program, details how in 1963, a group of local school district educators including Pauline Rojas, Joseph Hall, Rosa Inclán, and Ralph Robinett, created a “dual-language” immersion program for students in grades one to three in a school by the same name.

The school enrolled 350 students, half of which were native Spanish speakers and the other half native English speakers, teaching them in their home languages during the mornings and switching classrooms and teachers to learn content in the second language in the afternoons. The school enrolled 350 students, half of which were native Spanish speakers and the other half native English speakers, teaching them in their home languages during the mornings and switching classrooms and teachers to learn content in the second language in the afternoons. Through archival research and interviews, Coady was able to collect enough data to show that the program was an academic and social success. In the process, students of diverse backgrounds were also able to learn from and adapt to each other’s cultures. Through archival research and interviews, Coady was able to collect enough data to show that the program was an academic and social success.

Today, Coady says there are plenty of families across the state—some multilingual, some not—who are eager to see their children enrolled in this type of program. ProgressReport.co spoke with Coady to learn more about the history of Coral Way, and of Title VII, a now defunct part of the 1968 Bilingual Education Act that helped to fund and support bilingual education.

In honor of National Bilingual/Multingual Learner Advocacy Month, which takes place during April, ProgressReport.co caught up with Coady to learn more.

Q: What got you interested in bilingual education?

A: I’m in my 50s. I’m not Latina, but I grew up in a small diaspora, Italian-speaking bilingual community in the northeast United States. I was always interested in languages and my family’s heritage language in particular. So when I entered school, I wanted to study Italian but it was not offered as a language. I took Spanish as the ‘closest’ language linguistically to Italian. I studied Spanish and Latin American history ever since. In 1986, I was chosen as one of 25 students to represent the United States with the Organization of American States to live in Argentina after the end to the military dictatorship in 1983. We were the first groups of scholars to go to Argentina and study. I recall the strong military presence that was still evident in Buenos Aires at the time.

I subsequently moved to Europe to study business and French and attended the Sorbonne. I taught business English to professionals, as my first official teaching experience. I returned to the United States, worked at the Bank of Boston, and decided that I preferred to work in education. I did graduate work at Boston University in bilingual education, and eventually ended up at University of Colorado Boulder in the mid-to-late 1990s as a U.S. Department of Education Title VII Fellow and working with Dr. Kathy Escamilla.

Q: What is that fellowship?

A: Title VII was an offshoot of the 1968 Bilingual Education Act (BEA). The BEA was quite timely, because in the 1960s, language minoritized groups across the US, especially in Texas, Arizona, and California, were fighting for farmworker rights, for language rights, and civil rights. The BEA was introduced by Texas senator Ralph Yarborough, and it funded bilingual programs, and the preparation of teachers and scholars for bilingual education. By 1974 the US department of education offered assistance under the “Office of Bilingual Education and Language Minority Assistance” –OBEMLA–to support bilingual education and English learners. Unfortunately, and symbolically, that office was renamed in 2001 to the Office of English Language Acquisition, indicating the change in political sentiment away from bilingual education, despite decades of research showing positive outcomes from those programs.

Q: Is that where you learned about The Coral Way School?

A: In short, yes. I learned about Coral Way as part of my professional preparation and read about it, although the Coral Way ‘story’ was quite reduced in the books and textbooks to a mere few lines or maybe a paragraph. This book really changes that and adds a lot of depth to the Coral Way story and to the history of bilingual education in the US and Florida.

Florida has a tremendous footprint and history in bilingual education and bilingualism. The school opened on September 3, 1963. The superintendent at the time hired Dr. Pauline Rojas to identify a solution to assist Cuban refugee students in 1961. She was truly the mastermind behind the dual language program and its implementation in Florida. The Miami-Dade area had a significant number of non-English speaking students, and the district was at a breaking point in terms of funding and identifying supports for the teachers trying to teach content in English to non-English speakers. In that era more than 14,0000 children were flown from Cuba to the Miami area in an operation known as Pedro Pan. Parents in Cuba who feared the Communist regime felt it was the safest solution for their children. About 14,000 children were part of that operation. Few did end up at the Coral Way School, and while I’m not sure how many, Pedro Pan was incredibly influential in the local school district, then called Dade County Schools, because of the political context.

Q: So, tell us more about what’s in the book.

A: The book tells the story of how the program began and what happened in the first couple of years. I went through archives and oral histories, and I have some limited data on student academic achievement scores. Those tests, especially the language tests, were different than the kinds of assessments we use today, but the data are there, and the point I want to make is that Florida has made a tremendous contribution to the national landscape in bilingual education. We have been leaders in this area. We were leaders 55 years ago. It’s just incorrect to think that Florida is not a rich multilingual state, and our state policies should be proud of that fact, promote, and reflect it, rather than retreat to ‘official English.’ You can declare all you want, but that declaration doesn’t help the bilingual and multilingual children and families in this state. In fact, it harms them when we use that as an excuse, for example, not to provide Native Language Assessments in schools and to prepare teachers for bilingual students.

Q: From the perspective of Tallahassee, we’re often told that there just isn’t enough interest in bilingual education in this state. What’s your take?

A: We have a lot of problems to solve, but the first problem is we have some educators and many politicians who are not educated on what bilingual education programs are and what the research says. Florida today has more than 125 bilingual programs and they have grown with absolutely no help from the State at all, quite an embarrassment when we look across other states that offer bilingual teacher credentials, funding for bilingual training and curriculum and assessments. Importantly, Florida, especially Miami, is a gateway to Latin America and is significantly interconnected politically, socially, and economically. We need a more bilingual and obliterate populace, rather than continuing to assert mono-lingual English-only policies in education. We have White, educated parents in Alachua County, where there are no dual language programs, telling me, “We want dual language programs for our kids in Alachua County. What is wrong?” These include some bilingual families, but principally White monolingual families who have learned of the cognitive and linguistic benefits of dual language. In Sarasota, the bilingual educators and leaders in the community has been fighting for a bilingual dual language program and are finally able to open the Dreamers Academy this fall after several years of conflict. Geri Chafee, founder and interim principal, is a fierce bilingual advocate who has led the charge by challenging local bureaucracy and getting out the message to bilingual families.

Q: Some people feel like why implement dual-language learning if they themselves had to suffer through English-only programming. But what you’re saying is that actually a lot of Cuban exiles who came here as children didn’t have to suffer through it. What’s going on there?

A: We now have decades of strong and rigorous research showing the benefits of bilingual education and dual language in particular. Remember, Cuban refugee children and families were afforded access to additional language supports and bilingual education, to health care services, social services and so on, based on the fear of Communism so close to the US border. Other immigrant groups today are not given the same assistance across the board. When we know that bilingual education works and see academic, social, and cognitive benefits for those programs for students, why can’t we provide those programs to our emergent bilinguals from other countries?

Q: UnidosUS has spent the past several years pushing Florida legislators to implement a multi-grade Native Language Assessments bill. As a proponent of bilingualism, what is your perspective on this topic?

A: If you want to know how kids are doing in science, you test science. If you want to know kids’ reading comprehension, you test reading comprehension. If you want to know how well kids are doing in algebra, test algebra, right? That’s it. If you give it to them in a language they can’t read and write, they can’t demonstrate what they know in those areas. So you’re not testing science, reading, or algebra. You’re testing their ability to demonstrate algebra in another language. if we really want to know how students are doing in the English language, then we test the English language.

We’re not advocating for native language assessments for every student or for students who have never been educated through the medium of Spanish, for example. However, we are asking that for educators to be most efficient and effective in their work and use “best practices”, they need a starting point to align their instructional strategies, they need to know what kids already know in terms of academic content.

Troubling is that the State’s rationale for not providing native language assessments on their ESSA plan is factually incorrect. It is incorrect that using NLAs is invalid, which is what the state said. As I mentioned earlier, a valid assessment would separate out language and content as two different constructs. It is astounding to me that the secretary of education actually signed such a factually incorrect statement in the state ESSA plan and that the US Secretary of Education at the time, signed such a falsehood and approved it in 2018.

Q: So essentially, you see Native Language Assessments as a start, but you believe it really should help us to consider the even greater benefits of bilingual education?

A: Yes, no doubt. We had a great start in the 1960s in Florida but without a doubt, our state is about 30 years behind the nation in terms of high-quality bilingual and dual language programs, except for places where districts have themselves followed the research and implemented dual language. Some, like Orange County, have received private grant funding to do so. Imagine the possibilities if the state were supportive and on board? Imagine the possibilities if politicians knew how assessment worked and validity in assessments. Students deserve to have the best education possible. We can do that in Florida, but we need to take a hard look at how politics has negatively interfered with that process for our emergent bilingual students, EL students, and even monolingual students whose parents see the benefits.

Q: Why is this important not just to the individual student but to society as a whole?

A: We have an increasingly diverse population in the U.S. If we don’t give these kids the supports they need, we’re going to fail them and we’re going to fail ourselves. What will the state of Florida look like 20 years from now if we continue not to implement these kinds of programs? I don’t have a crystal ball, but I can pretty much tell you just by where we are today that we’ve become fossilized into these old ideologies. In 2040, I’ll be retired, but I’ll be sitting there wondering “what happened to our bilingual kids? How come we squandered all of our linguistic resources?” That will be a sad day in Florida because we’ll be looking back at 75 years of stagnation.

Q: It seems like a startling prospect. Florida is such an international place, and it’s geographic location is so strategic for all of the Americas, as well as other continents on the other side of the Atlantic. If it were a country, it might be one of the top 20 largest economies in the world. Can you tell us a bit about how Coral Way School’s bilingual program may have contributed to that kind of growth?

A: People will tell you, “this program changed my life.” The principal, director, teachers, and aides were incredibly serious about developing high levels of Spanish and English and literacy for both groups of kids. The kids learned both languages and became very successful academically and socially. In fact, I haven’t met anyone who was in the program between 1963 and 1968 who was not academically and economically successful. I found one person who was rather ambivalent about the program, but the vast majority acknowledged how the program shaped their lives and livelihoods. Many were highly successful. For instance, Orestes Gonzalez became a successful New York businessman and publisher, Amy Porter Dessaux is a multilingual living in France and strong advocate for bilingual programs, and Stuart Singer became a litigation attorney and advocates for children’s Medicaid in Florida. Others repeatedly stated that their views about cultural diversity and difference were significantly shaped by the program.

Q: Any suggestions for how we can demonstrate this type of success with numbers?

A: That’s what Leo Gomez did in Texas. He only asked the state to provide a data point where school districts could indicate the program model that the EL student was enrolled in. So, districts might say, for example, that Maria Coady participated in dual language in grades 1, 2, and 3. Then after three or four years of data, scholars examined the student learning outcomes and compared those students who were in dual language, bilingual education, and other models like sheltered English. The data showed that the kids in dual language outperformed others not in dual language. It was an obvious argument for the state to then support bilingual education and dual language programs in Texas. In Florida, our categories of “language program model” are so outdated when districts report, there’s no way to accurately know that, and there is no indicator for “dual language” in the reporting. It doesn’t cost a penny to fix that problem.