HISTORY LESSON & CLASS PROJECT: Educator Karina Wong Talks About Her Asian and Latino Heritage and Her Ideas for Inter-Racial Solidarity in All Forms

THE HISTORY LESSON:

Nearly seven decades ago a boy named Wong Sun Dack boarded a ship from his impoverished community Toisan, China, and came to America to start a new life. It’s a story common in the news today. Economic troubles—in this case, tensions between China and Japan—force a family to seek opportunities elsewhere. But rather than the United States, the Wong family went to Mexico.

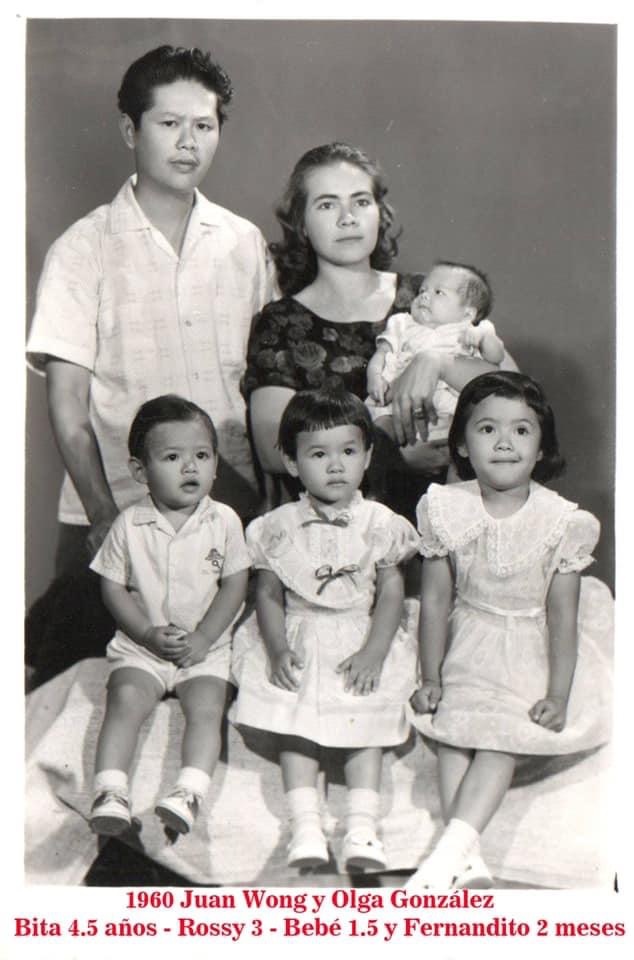

Sun Dack, then just 11 years old, arrived in Baja California, where his father was waiting for him. His mother joined them in the late 1960s. Sun Dack was raised in the border town of Mexicali, and became a business owner. He married a Mexican woman named Olga, and they had five children.

Flash forward two generations. Sun Dack’s granddaughter, Karina Wong, grew up across the border from Mexicali in Calexico, California, after her parents made their own immigrant journey to the United States. Karina and her sisters, Karla and Karen, were born in the United States. Karina remembers splitting her time between the family homes in Calexico and Mexicali until she was about four years old. She now lives in San Diego, where she is raising her two children with her husband.

Karina Wong is often mistaken for Filipino. “My brown complexion and slightly slanted eyes always make people curious about my ethnic background,” she says. “I find the assumption of Filipino amusing. It is a great conversation starter that welcomes dialogue across different people.”

The Philippines aren’t in Latin America, but those Asian Pacific Islands were also colonized by Spain. In fact, during colonization, many Filipinos—sometimes imprisoned or enslaved—came with the Spaniards to Latin America and the Caribbean. In the 1800s, when African slavery was abolished, hundreds of thousands of Asians from countries such as China, Japan, Korea, and India migrated to the region, often as indentured servants. Even today people from all over the world migrate to Latin America, and people from Latin America go to many other parts of the world, not just North America.

This complex history is a reminder that Latinos are made up of many races and cultures. Since May is Asian Pacific Heritage Month, ProgressReport.co wanted to explore Asian-Latino identity, and Asian and Latino solidarity. Both are topics Wong has looked at as a former English as a Second Language instructor with AmeriCorps, and currently as a community leader, a mother, and a person identifying as an American of Asian and Mexican descent. This mixed identity fuels her quest for civic engagement, especially in today’s climate of fear.

“My life is a cultural bridge that influences my love for my community. My Chinese and Mexican culture leads my actions in supporting others,” says Wong.“ As an educator of mixed race, I would love for our classrooms to feature many different cultures. Through students learning about different historical journeys, students will be able to see everyone’s ‘funds of knowledge.’”

“The term funds of knowledge refers to historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills,” she explains. “Classrooms should be a space where the students’ backgrounds are known, celebrated, and utilized to support lessons. Through using ‘Funds of knowledge’ in our classrooms, educators are able to create a more inclusive learning environment.”

Dipping Into the Fund of Family History

Ideally, Wong wants English learners (ELs) to maintain their home languages while mastering English, but she also knows from her family’s experience how hard that can be.

Wong’s grandfather continued to speak Cantonese long after leaving China for Mexico. But there were many obstacles to teaching it to his children. Olga and Sun Dack’s two eldest daughters attended Chinese school but only briefly. They felt they didn’t belong. Wong’s grandparents saw learning English as a way for their daughters to integrate and assimilate on both sides of the border, so they sent them to schools in Calexico. Their two sons attended school in Mexicali.

Because of this history, Wong never had the opportunity to learnCantonese from her father. She sees that as a significant loss, a missed opportunity. In the absence of that ancestral Cantonese, Wong has found other ways to reaffirm her multi-dimensional identity. For starters, she kept her Chinese surname, and hyphenated her and her husband’s family names, making Quintero-Wong her children’s last name. But she and her husband still have the asset of being bilingual in Spanish and English, and that’s something they want to promote to their family, especially while their children are still young. But she knows bilingual or multilingual teaching can be an uphill battle.

“It’s hard to push Spanish outside our home, especially in our mainly White neighborhood in San Diego,” says Wong. “We have met many white parents that applaud our decision to raise bilingual children, as they themselves are trying to teach their children Spanish. It is comforting to know that this approach will be beneficial to our children in the future. We are includers. It is very important to raise our children among many cultures. We believe that by modeling this to our children and leading conversations with other members of our community we strengthen cultural American ties.”

Knowledge Funds that Grow the Cultural Coffer

During her six years working with elementary English Language Learners, Karina has supported students with their language transition through in-class intervention, which can be crucial to help at-risk students read grade level material. In 2015, Karina, in collaboration with the Calexico Library, started a Spanish Summer Reading Program where elementary students where students practiced their Spanish through literacy and art activities. It was one of Karina’s first community projects supporting students’ cultural identity.

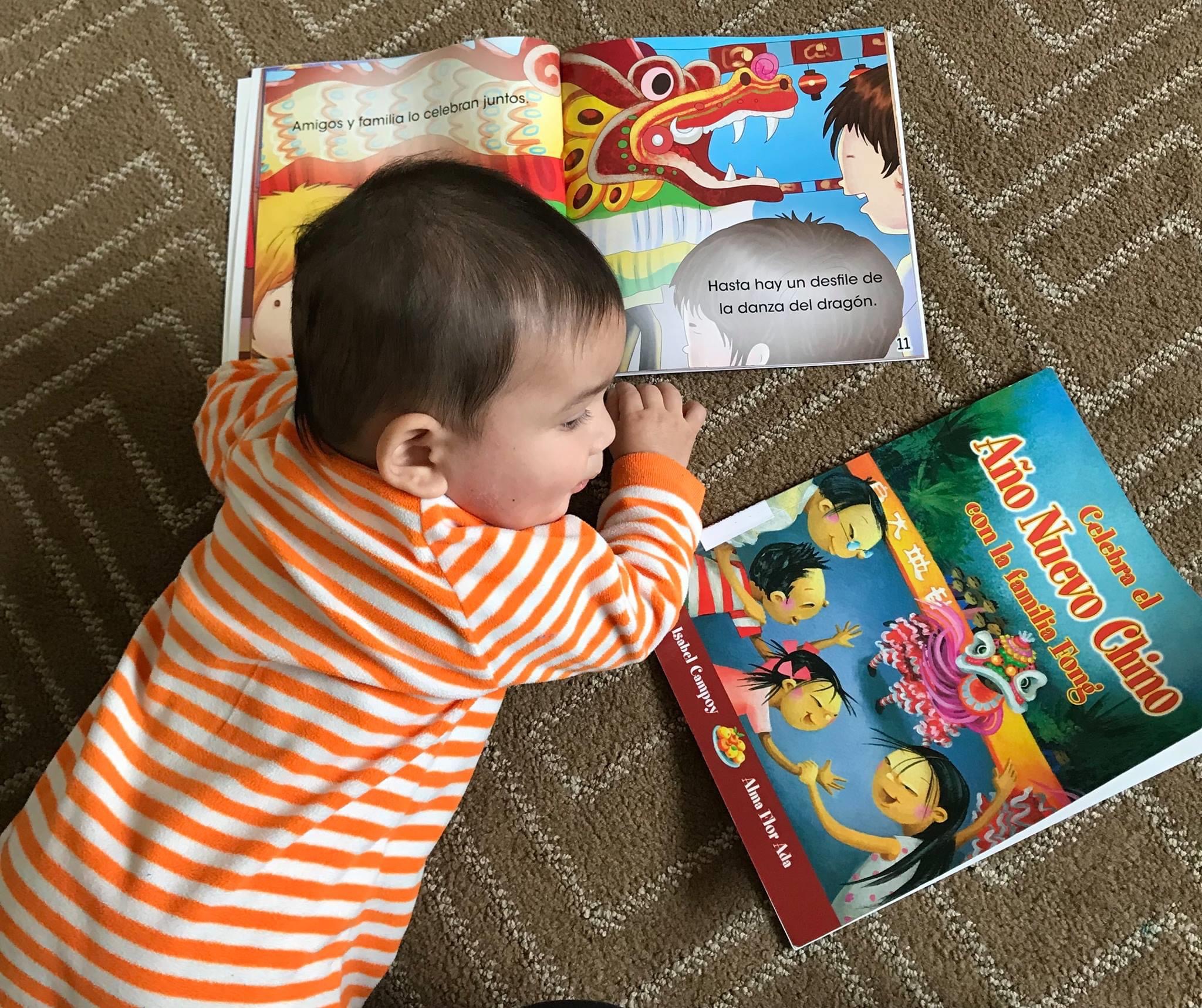

“I wanted Calexico students to have the opportunity of learning some Spanish so that when they are older they won’t regret not learning it at an early age.” Now, as President of the Friends of the Mission Valley Library with San Diego Public Library, her role is to support library programs. “This gives me the opportunity to create a space where different cultural, social, and economical backgrounds are able to interact,” she says, noting that the San Diego Public Library offers story time in Spanish and Mandarin, as well as a Lunar New Year Celebration. She says these activities help her to “celebrate my culture among my community. ”

Karina also volunteers with MANA de San Diego, a nonprofit organization that empowers Latinas through education, leadership development, community service, and advocacy. Karina serves as an Hermanitas mentor, mentoring a high school junior and is part of the scholarship committee. “Through my service to my community I hope that I am able to support underrepresented communities,” she says.

This year’s Asian Pacific Heritage Month is coming to an end and Hispanic Heritage Month won’t arrive until late September, but why should those be the only times to teach this kind of history and culture? Most civil rights activists would agree that America’s current climate of fear has stoked already existing racism and xenophobia. And the coronavirus pandemic has fueled anti-Asian racism in the United States, starting with early reports of the outbreak in China.

Wong worked with ProgressReport.co to come up with several curriculum ideas that can help to celebrate this unique Latino and Asian connection but also consider diversity and solidarity in all its forms, in any week of any month.

THE CLASS PROJECT:

Map Out Asia-Latin America Migration

Whether the students you’re instructing are just your own at home or a whole virtual classroom, you can have students poke around online to see if they can identify which Asian communities migrated in great numbers to certain parts of the Americas—North, South, and Central. Have them pick a subtopic, such as Japanese migration to Peru or Chinese migration to Cuba, and then dig deeper. Here are a few sample questions:

- What was the historical context of their migration?

- How did they influence the culture, food, aesthetics, or beliefs of their adoptive countries?

- Are there any historical landmarks in those places today? Can you find pictures of them?

- There are many stories of cultural merging, like that of Wong’s Chinese grandfather and Mexican grandmother. Can you find some in those case studies?

- Migration doesn’t only go East to West. Can you find examples of large populations of Latin Americans who settled in Asia?

Take it Stateside

In some U.S. communities, such as Los Angeles and Seattle, historic Asian and Latino populations are based in close proximity to each other, and there is a lot of exchange between them. In other communities, that might not be so common. Ask students to consider who lives in their town, where they are mostly concentrated, and what they might know of their interactions.

- Do these communities cohost cultural events?

- What about community outreach and civic engagement programs?

- Can’t find anything online? What groups can you call to find out?

Find a Historic Case of Solidarity

One of the most important shows of solidarity between Asians and Latinos in the United States actually centered on a Supreme Court case involving civil rights and education.

In 1972, the Puerto Rican educational nonprofit ASPIRA and the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund won a lawsuit against New York State City Board of Education after it was found that the school system had not provided equal learning opportunities to students because of their ethnicity and native language. Two years later, ASPIRA joined forces with a group of Chinese parents in California in a legal battle to for native language assessments. The case, known as Lau v. Nichols, landed in the Supreme Court where it was unanimously decided that not attempting to provide supplemental language instruction to English learners violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“The Lau case remains an important decision for bilingual education that reminds us how all minorities in the United States deserve appropriate support in our education system,” says Wong.

Building a Solidarity Campaign Today

Finally, there’s no time like the present to come up with ideas that teach tolerance, celebrate diversity, and foster solidarity among those most suffering from America’s climate of oppression. Stories of violence and vandalism against historically under-represented groups such as Latinos, Asians, African Americans, indigenous peoples, members of the LGBTQ community, women, and Muslims—make the national news every single day.

There are dozens of high-profile incidents to explore in the past year alone:

Crimes against Latinos have spiked since the Trump Administration’s calls for a border wall and its crack down on immigration. In August, Patrick Wood Crusius opened fire in a Walmart in San Antonio, Texas killing 23 people and injuring 23 others. He told authorities he was aiming to kill Mexicans, and it has been recorded as the deadliest attack on Latinos in recent U.S. history. In November, a White man named Clifton Blackwell was charged with a hate crime for throwing acid on a Latino named Mahud Villalaz as he was entering a Mexican restaurant in Milwaukie, Wisconsin.

The media has highlighted numerous killings of African Americans at the hands of police officers. Last October, a Black woman named Atatiana Jefferson was fatally shot through the bedroom window of her home in Texas by White police officer Aaron Dean. He was responding to an early morning safety check made by a neighbor who noticed her front door had been open for several hours, White vigilantes George and Travis McMichael shot Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery to death while jogging. In March, police shot eight rounds of bullets into EMT Breonna Taylor while she was sleeping in her Louisville, Kentucky apartment. They said they had entered the home executing a drug warrant, but the man did not live in her apartment complex and had already been arrested. Hearing people enter the home unannounced, Taylor’s boyfriend Kenneth Walker fired a shot with his gun, and police responded by firing 20 rounds throughout the house.

Just as ProgressReport.co was putting together this feature story and lesson plan, the nation watched Amy Cooper, a White woman on video screaming at Christian Cooper, a Black man, in New York City’s Central Park threats that the police would take her side and not his because of her racial privilege. The same day, a video depicted Derek Chauvin, a White cop in Minneapolis, kneeling for eight minutes and 45 seconds on the neck of George Floyd, a Black man. Floyd cried in agony that he couldn’t breathe, yet neither Chauvin nor his fellow officers at the scene, ones of several races, Thomas Lane, Tou Thao, and J. Alexander Kueng intervened on Floyd’s behalf.

Who were they in solidarity with and why?

“As I read about George Floyd, I quickly became aggravated by how easily police brutality can keep taking the lives of Black people in our country,” Wong says. “It saddens me that all four police officers never held each other accountable and let this death occur. As a country, I believe we have lost a sense of responsibility of standing up for those in need. As Benjamin Franklin once said, ‘Justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are.’”

And what about the recent attacks on people of Asian descent? Ever since COVID-19 was traced to China, Trump has been relentless in blaming China for it spread and even calling it the “Chinese virus.”

In March, Jose L. Gomez was accused of stabbing three members of an unidentified Asian American family in Midland, Texas. According to law enforcement reports, he said he did it because family members “were Chinese and infecting people with coronavirus.” In April, three 15-year old girls were charged with hate crimes after for attacking a 51-year-old Asian woman on a bus in New York. They allegedly hit her head with an umbrella while making anti-Asian statements and saying she caused coronavirus.

What beliefs, sentiments, political structures could have fueled these acts?

These problems in our society continue, so how do we prepare for the next crisis in the headlines? And the ones that don’t make the press?

For Wong, the key is tapping into those funds of knowledge, all throughout the year. History and culture lessons give students the pride, strength, and sense of wonder they need to tackle both their studies and the issues they face in today’s society.

In thinking about teaching Asian Pacific Heritage, Wong says she would have students explore the history of Asians in the Americas through online research as well as presentations of videos, pictures, and books depicting their contributions. That might include a few episodes of the new five-hour PBS documentary series Asian Americans. Or it could lead to an activity in which students analyze the names given to buildings around their city, and which ones might merit a name change based on what community leader really made a deep contribution and hasn’t been recognized.

And talking about the discrimination of one community lead to a discussion of all of the above? Wong hopes so.

“As a problem-based assignment, I would have students create a hate crime prevention presentation to all school staff and students,” she says. “Training would support anti-bias ideology and conflict resolution methods. Student-led training would cover procedures for identifying hate crime and incident reporting. Topics covered would be religious, racial, sexual harassment, and discrimination. Students would also cover strategies for preventing incidents and resources available for dealing with these incidents. Students would also be encouraged to team up with law enforcement and community organizations to support a new school and community culture.”

“Most importantly, as an American, I hope that our country is able to come together in our next elections and truly analyze our state and local elected officials,” Wong says. “Our leaders’ true colors showed these last few weeks and it is up to us as citizens to hold our elected officials accountable in creating unified communities that support families across the United States. Through inclusion, respect, and community connection we will be able to thrive as a country.”