Asian Latinx Educators Reflect on the History of Asian Immigration to the Americas in Honor of Asian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

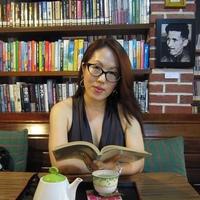

When Dr. Junyoung Verónica Kim enters her Latin American Studies classroom, students often assume that since she’s of Asian origin she is not a native Spanish speaker. Most jump to the conclusion that she’s not from Latin America. But when she starts speaking to them in a quintessentially porteño accent, the mark of a resident of Buenos Aires, their bewilderment is amplified even more.

“Some students have admitted to me apologetically at the end of the semester that they were initially worried that I might not be qualified to teach Latin American Studies since they assumed that I had no connection to Latin America, and probably spoke poor Spanish,” she says.

Many Asian Latinx academic have had similar experiences. Some have been inspired by these scenarios to research why their intersectional history is so underrepresented. In honor of Asian Pacific Heritage Month, ProgressReport.co spoke to several Asian Latinx educators on the pursuit to insights into how to better teach history, celebrate diversity, and combat racism and xenophobia. The project came to fruition this week as Congress passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, a government response to an increase in anti-Asian violence that has been largely attributed to the pandemic, its supposed origins in China, and the current trade war between Washington and Beijing.

Merging Area and Ethnic Studies

Dr. Kim, assistant professor of visual culture and media and Latin American culture and literature at the University of Pittsburgh, says using ethnic studies as the principal driver for anti-racism curricula creates blind spots, because it often gets confined to the North American experience. She says taking a broader geographic approach can make those intersectional experiences more obvious.

“Because of the way they (academics) bound off area, or define ethnicity, they’re unable to see the relationality,” she says. “I always argue that these unknown stories are important, but in order to actually get a full perspective of what is going on now, you need to understand what went on. The past is always the present and the present is always the past.”

Having spent her formative years both in Seoul, South Korea, and in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Dr. Kim internalized the ways in which these places––usually viewed as unrelated––are intimately connected, through centuries of global economic and political currents.

She encountered first-hand the complex ways in which the logic of the Cold War was propagated and normalized. In South Korea, she was required to make anti-communist speeches against North Korea. A similar expectation was projected onto school children in Argentina, which was just emerging from a civil conflict and military dictatorship during the 1970s and 1980s.

“This global relationality was not just a symptom of the Cold War, but part and parcel of the global political economy that dates back to at least the 15th century with the conquest of the Americas which, although not widely acknowledged, sparked Asian migration to the Americas,” she explains.

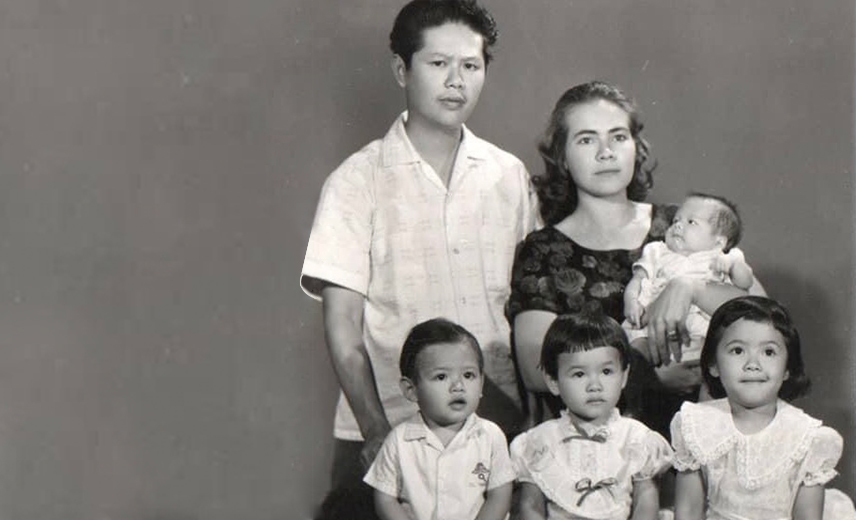

Spain colonized the Philippines and the Americas at the same time, so many Filipinos came to the Americas in the 16th century as sailors, soldiers, prisoners, or because they were directly enslaved by conquistadors. The Manila Galleons transported commodities across the Pacific, but they also carried countless slaves from all over Asia to the Viceroyalty of New Spain (today Mexico). Dr. Kim suggests Tatiana Seijas’s comprehensive study, Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians, for those interested in learning more about this commonly overlooked chapter of transpacific slavery during the Colonial Period in the Americas.

Following the abolition of slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean, workers from China and India emigrated as indentured servants, often working alongside and intermarrying with the formerly enslaved Black workers and their descendants. In fact, it often surprises foreigners visiting Cuba that Havana has its own Chinatown, or that people others might identify as being of mixed African and European heritage will note that they are also Asian.

Peru was the first country in Latin America to establish diplomatic relations with Japan, and it began accepting immigrants in 1873. Today, it has one of the world’s largest Japanese communities outside of Japan. In fact, it’s second only to Brazil, which has about one million people of Japanese descent.

These Asian communities continued to grow in Latin America as a direct result of anti-Asian immigration policies in the United States. In 1882, for example, the U.S. government enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first law to ever prohibit immigration of a particular ethnic group. It came just as the California Gold Rush, which had spurred a large number of Chinese workers to come to America, was winding down and animosity over competition for jobs began to grow. In 1907, the United States and Japan created what became known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement, an informal deal in which the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigration if the Japanese government would not issue passports to citizens who might be trying to head to the United States.

Around the same time, in 1904, as the Japanese Empire began territorial acquisitions that included the annexation of Korea. Many Koreans left for Yucatan, Mexico, becoming the first Korean migrants to the Americas.

“These migrants, who were falsely promised wealth and prosperity by Mexican and Japanese labor brokers, were sold into indentured servitude to large henequen planters in the Yucatan,” explains Dr. Kim.

This initial migration spurred Korean diasporas in Cuba, Guatemala, California, and other parts of Mexico as some of these migrants and their descendants left Yucatan. Others stayed and formed a Korean-Mayan community centered around Merida. Some of these migrants also fought on different sides of the Mexican Revolution. The arrival of multiple Asian migrant groups was not peripheral, but critical to the construction of the modern Mexican nation-state.

Dr. Kim recommends Jason Chang’s book Chino: Anti-Chinese Racism in Mexico, 1880-1940 for the way it highlights anti-Chinese racism during the Mexican Revolution and uncovers historical atrocities against Asians, such as the Torreon Massacre in 1911, where more than 300 Chinese people were murdered in a span of two days. Systematic ethnic cleansing and deportations of Asian populations are a common feature of the history of Asians in the Americas, from the massacre of Chinese people in 1871 in Los Angeles and the massacre of Chinese indentured workers in Peru during the South American War of the Pacific (1879-1884), to the ethnic cleansing campaign in El Salvador in the 1930s and 40s, in which indigenous peoples were killed and Chinese and Black peoples deported.

The United States’ anti-Asian immigration policies were nullified under the Immigration Act of 1924, but anti-Asian policies soared again in the United States after Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, which led to the United States’ formal entrance into World War II. The U.S. government began placing people believed to be of Japanese origin into internment camps. The U.S. emergence as a hemispheric superpower contributed to the spread of this anti-Asian sentiment across much of Latin America. For example, in 1942, Peruvian authorities rounded up some 18,000 people of Japanese descent and shipped them to U.S. internment. Most Latin American countries followed suit.

When the war ended, Latin American governments did not allow those deported to return, forcing them to stay in the U.S. as undocumented immigrants. Others had chosen deportation to Japan, instead of internment in U.S. concentration camps, and were killed in Japan during the war. Some perished in the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“The documentary film, Hidden Internment: The Art Shibayama Story, provides an illuminating exploration of the tragic experiences of Japanese-Latin Americans during World War II, and the violent dismissal of their experiences by the governments involved in our present day,” adds Dr. Kim.

In her course, Border Studies: National Borders & Social Boundaries, Dr. Kim weaves this history into current concerns around the detention of Central American migrants, the policing of Black and Brown bodies, sex discrimination and violence against women, and capitalism.

She draws parallels between the history of racialization and exclusion of Asian migrants in the Americas and the current crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border, as well as the precarious situation of the more than 11 million undocumented workers in the United States, which is largely driven by the ways the United States’ Cold War foreign policy in Latin America fueled internal conflicts and contributed to a culture of violence, prompting so many to flee for safer places and better economic prospects.

Some of the books that help her stitch these themes together are:

- How to Hide an Empire by Daniel Immerwahr

- Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings by Juana María Rodríguez

- Their Dogs Came with Them: A novel by Helena María Miramontes

- Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding U.S. Immigration for the Twenty-First Century by A. Naomi Paik

- Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, by Naomi Klein

Comparative History and Popular Culture

Another Korean-Argentine academic, Dr. Chisu Teresa Ko, prefers not to share so much of her own story, but likes to use storytelling to highlight shared experiences between cultures. Ko, a professor of modern languages and coordinator of Latin American studies at Ursinus College in Pennsylvania, says that since Asian heritage in Latin America has been overlooked for so long, she often eases into it by exploring ethnic heritage that has gotten more recent media attention. One such example is the Afro-Latinx movement across all of the Americas. It’s increasingly common for a global public to consume news or documentaries of it stemming from places like Colombia, Brazil, Cuba, or Mexico, but harder for some to grasp that countries like her native Argentina share a similar history, so that can open discussions on Latinx diversity.

“It’s really been a point of discussion in the past 20 years, thanks to the work of Afro-Argentine and Indigenous activists,” says Dr. Ko, noting that for at least a hundred years, Argentina managed to project itself in pop culture and self-references as a country of European origin. But it shares a history of African slavery, exploitation of Indigenous peoples, indentured servitude, and migration of people from across the globe who fled their homeland for economic or political reasons.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mZ6FQfIP0EI

Dr. Ko also suggests comparing Asian Latinx films to films about Asians in North America. For example, the documentary Halmoni, directed by Daniel Kim, depicts how decades ago a young Korean couple plans to migrate to Buenos Aires but winds up in chilly, isolated Patagonia creating a successful plant and vegetable business out of greenhouses. She likes to show it alongside the 2021 film Minari by Lee Isaac Chung, depicting a Korean American family moving to Arkansas’s rugged and not-so-diverse Ozarks to fulfill their dream of starting a farm.

“It’s the same story. They all find themselves in a very remote, harsh environment,” says Dr. Ko. The difference, she says that it’s still easier for audiences in many countries to imagine such a scenario in the United States because the works of Asian Latin Americans have simply not been showcased.

“There are very few authors or cultural producers of Asian descent who have a platform in Argentina and in Latin America, noting that watching these films in parallel can drive a conversation about the shared experiences of the Korean diaspora across the Americas while discussing who has access to producing pop culture and how audiences in the Western Hemisphere then consume it.

Dr. Ko also mentioned the documentary Mi útlimo fracaso about the intimate lives of three women identifying as Korean and Argentine. It hasn’t found its way into mainstream media sites, and in an effort to reach a wider audience, director Cecilia Kang allowed Dr. Ko to post her email address in a recent article Ko wrote about Korean-Argentine documentaries. Anyone who wishes to see the film or screen it for educational purposes can write to her.

Confronting Stereotypes

It’s often said that Asians are the “model minority,” suggesting that they don’t experience the same oppression as other people of color. But that, too, is a stereotype. People of Asian descent are often looked at not yet citizens even when they were born and raised in the Americas, notes Dr. Kim.

“The Asian needs to always been seen as a perpetual foreigner, as a possible terrorist or spy,” Dr. Kim says. She notes that Asian scientists often face suspicion of collaborating with U.S. rivals like China. “Stereotyping Asians as smart and cunning can be very violent,” she says.

Some media called out anti-Asian hate after a March shooting in Atlanta in which gunman Robert Aaron Long opened fire on several Asian-owned spas killing eight people, six of whom were women of Asian descent. But many mainstream news outlets stopped short of confronting the anti-Asian misogyny of the attack.

“I’m really surprised by the media. Even when speaking about anti-Asian racism, they can’t seem to speak about racialized sexism against Asian women,” Dr. Kim says. “I don’t know if it’s because of shame or guilt that people have a really hard time talking about it, but the utter horrible stereotypes about Asian women have prevailed.”

For Dr. Kim, attacks like this cannot be separated from the practices of Western imperialism that waged so many wars in Asia. This violence included tactics such as rape and sexual exploitation of Asian women, while hypersexualizing and dehumanizing them as exemplified in the racial figure of the geisha in films and books, such as Madame Butterfly, Miss Saigon, and Memoirs of a Geisha.

“The raping of Asian women has often been seen as voluntary, and if you look at most movies about the Vietnam War, Vietnamese women are cast as willing prostitutes, as willing victims,” she says, noting this underscores the importance of looking at ethnic studies and anti-bias and racism curriculums through a broader geopolitical lens.

In fact, by doing so, students might start to draw parallels to the mass rape and sexualization of Indigenous women in the Americas. In Spain, for example, it’s common for people to emphasize that the United States was largely founded on the near extermination of Indigenous peoples, whereas Spanish and Portuguese colonization is considered to have been friendlier, even going so far as to say it was common for Iberian colonizers to “make love” to the locals, producing what many now refer to as criollo or mesticized populations.

The recent rise of anti-Asian violence is not limited to North America, but also extends to the rest of the Americas. Rachel Lim’s essay, “Racial Transmittances: Hemispheric Viralities of Anti-Asian Racism and Resistance in Mexico,” calls our attention to the ways in which the current racialization of COVID-19 becomes interwoven with older forms of anti-Asian narratives, often specific to that local and national context. For instance, a recent episode of a popular Chilean comedy show included a racist parody of the Korean boy band BTS that assembled different stereotypes about Asians: representing Asian languages as nonsensical gibberish, mocking stereotypical Asian facial features, criminalizing Koreans through the figure of the North Korean president, ridiculing Asian names, and associating Asians with the coronavirus. This type of practice is ubiquitous in Latin America where anti-Asian racism is considered harmless and “all in good fun.”

Fomenting Solidarity

Catalina Kaiyoorawongs, a graduate of the UnidosUS National Institute of Latino School Leaders (NILSL) and former associate executive director of UnidosUS’s Florida Affiliate UnidosNow, isn’t Latina, but she has always made a point of talking about her shared identity with that community, and how it has fueled her career in education, entrepreneurship, and social justice. She was born in California to a White working-class mother and a father who came to America as an economic immigrant from Thailand. At one point, she went back to study in Thailand. But a South Asian financial crisis left her parents without the money to pay for her schooling. They moved back to the United States and settled in a rural part of Florida where Kaiyoorawong found herself studying alongside many Latino migrant children.

“We often see race, but so much of your experience has to do with your socio-economic upbringing,” she says, noting that she finds herself spending a lot of time dispelling the myth that people of Asian descent come from money. “South Asians are mostly economic refugees just like Latin Americans,” she adds, noting that many of them have made perilous journeys by land and sea or have fallen victim to human trafficking, experiences immigrants from many parts of the world have faced.

As an adult professional enrolled in the NILSL program and working in UnidosNow, her role was to help prepare underserved students for academic success. In the process, she discovered she was drawing from her own experiences. In fact, she found that coordinating strong tutoring programs or helping students learn to fill out financial aid forms for college was just part of the solution.

“So much of our college prep program was about esteem building and helping people understand the value of that,” she says. “Part of combating racism is about having enough esteem in who you are and what you bring, having the courage to share your journey and your truth.”

In a feature ProgressReport.co story for last year’s Asian Pacific Heritage Month, Karina Wong, an educator of Chinese and Mexican descent based in Southern California, described this practice as dipping into every student’s “funds of knowledge.”

“Classrooms should be space where students’ backgrounds are known, celebrated, and utilized to support lessons,” she said, noting that encouraging multilingualism is one of the best and safest ways for students to engage in that process.

Dr. Kim says the “growing diversity of student populations” influences the questions she explores in her classes as much as her own research. “As struggles against racism, sexism, dehumanization, and dispossession, have become more visible in part because of the ubiquity of personal recording devices and social media,” she says, “students have become more invested in examining the historical processes of racial capitalism, settler colonialism and imperialism, and in turn imagining reparative alternatives and envisioning transformative futures.”