Arizona’s Superintendent of Public Instruction Starts New Year with Push to Repeal English Language Blocks

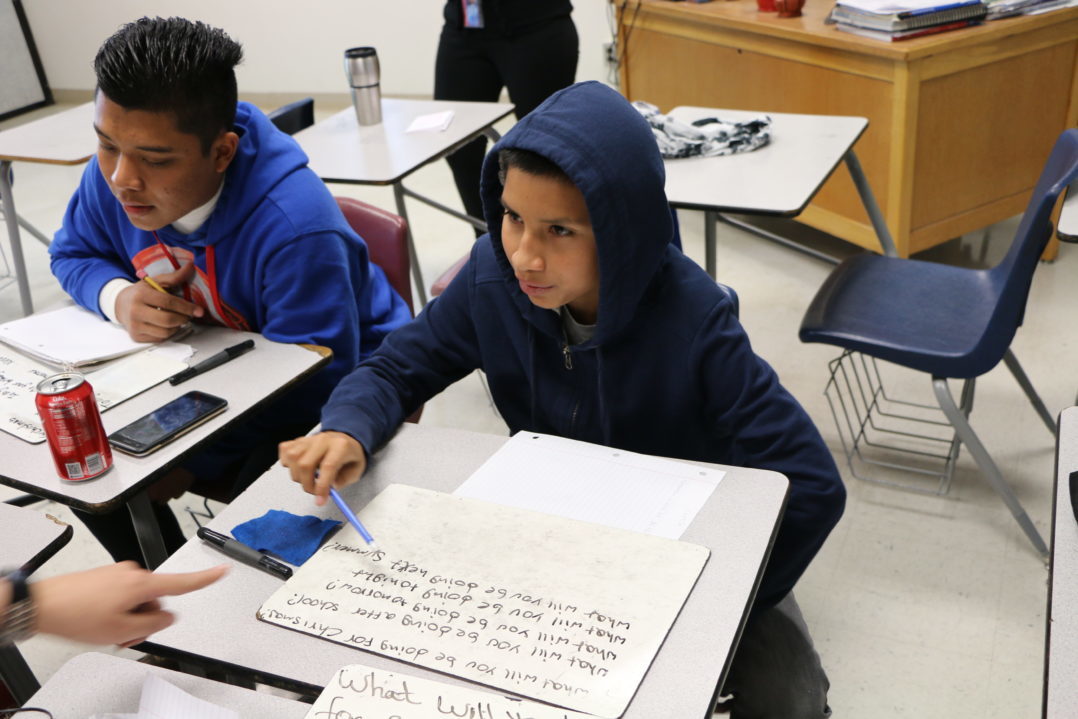

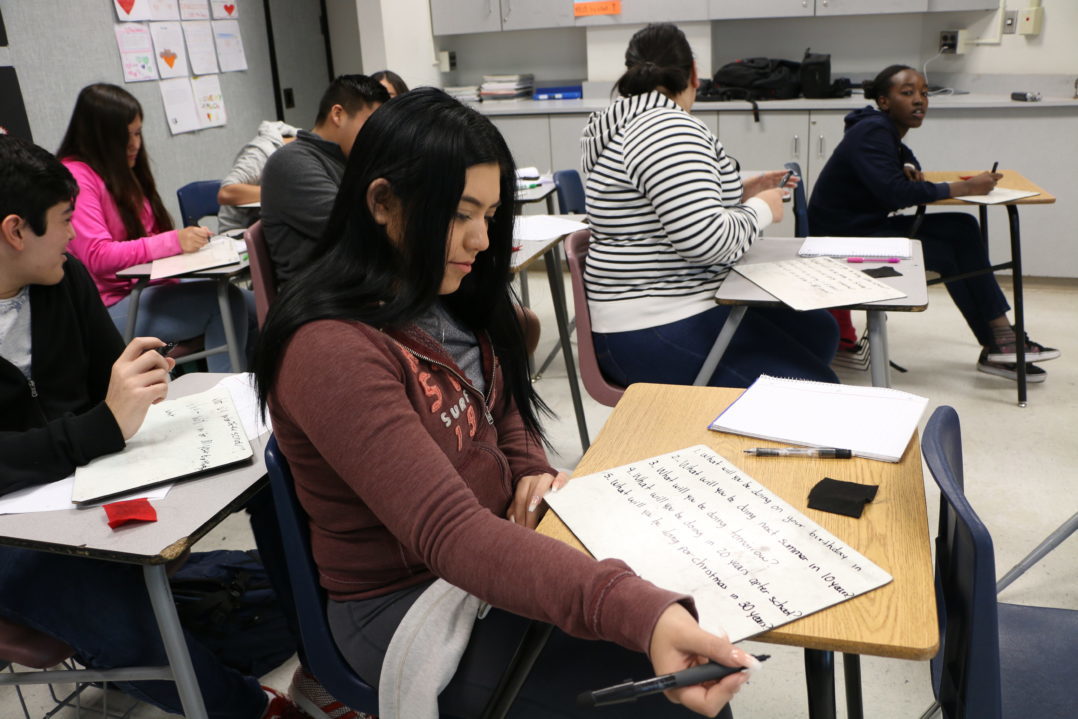

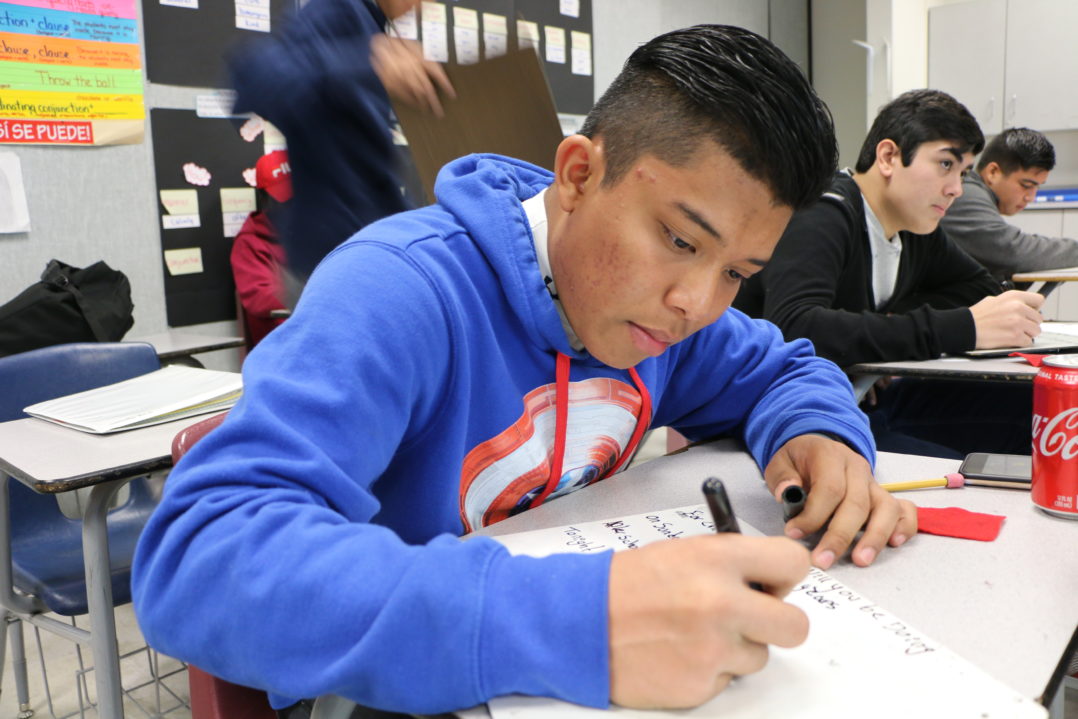

On a crisp November day, Tucson High School Teacher Stephanie Fernandez-Ramirez asks students enrolled in her four-hour English language class to answer a handful of basic questions about the future: What will you be doing this weekend? What will you be doing for Christmas? What will you be doing five years from now? What will you be doing 20 years after high school?

“I want to study to be a dentist,” says Zohar Abdallah, a 14-year old immigrant from Mexico, who is still struggling to incorporate the future continuous tense – the “ing” verb form.

Her classmate Lupita Espinosa, 18, got the tense right but says keeping up with this class and her other homework requires she study more than three hours a night.

“In five years, I’ll be working in my field,” says Espinosa, who hopes to become a doctor.

Arizona’s newly elected State Superintendent of Public Instruction Kathy Hoffman wants to see her students fulfill dreams like these, but she takes office this month knowing few English learners (ELs) will get there without major changes to current state policy and practice.

Arizona currently requires ELs that score below proficiency on the state’s assessment for English language proficiency, called AZELLA, to attend four-hour daily blocks of what it calls Structured English Immersion (SEI), where students are primarily focused on learning the English language. Civil rights activists and education advocates have largely criticized this program. They say it prevents students from learning core academic content and segregates those who are English dominant from those who aren’t, all of which could be factors in lower achievement levels and higher drop-out rates among ELs in the state.

According to National Center for Educational Statistics study from the 2013 to 2014 school year, only an estimated 18% of Arizona ELs graduated high school, compared to 76% among their native English language peers. Meanwhile at the national level, US Department of Education data shows that English learners graduate high school at a rate of 63%, compared to 82 percent of the overall graduation rate.

“To me, this represents an opportunity in our state. They have so much potential. We need to view their multilingualism as a professional asset and a benefit rather than a deficit,” Hoffman told participants of a November Arizona Education Policy Summit hosted by UnidosUS in Phoenix.

These same advocates have been working on bills to limit the number of hours that children are enrolled in English language blocks and to provide waivers to opt out of the SEI block. They also favor dual language instruction models, which are currently prohibited under a voter-approved law requiring ELs receive instruction only in the English language until they have reached a high level of proficiency in that language.

The current practice is especially difficult for high school students like the ones enrolled in Fernandez-Ramirez’s class because the older the students, the more barriers they have. As young children, their brains record new languages more easily, and there’s less social stigma around stumbling through improper grammar. Teenagers, on the other hand, have a lot more going on. Their bodies are rapidly changing and developing which can be exhausting and confusing; they feel more anxious about fitting in; and immigrant and refugee families may be pressuring their teens to get out of class and get working to support the household.

“I’m not a fan of the system,” says Fernandez-Ramirez. “It’s nice for the students who are brand new here because they build their little culture within their classroom, but they are very isolated from the rest of the students.” And that can impact how they see themselves when they go back into their core classes, she says.

“At this age, they really care about what their classmates think so they’re a lot more scared about making mistakes,” says Fernandez-Ramirez.

Fears like that even make basic physical education courses feel daunting, says Abdallah.

“When I go to P.E., I feel so confused,” she says, wincing. She says it’s embarrassing to try and follow instructions around students who haven’t been as sensitized to her language challenges because she’s not integrated with them throughout the day.

This can lead to a reluctance to participate, and it’s through participation in all courses that students develop into well-rounded young adults, notes Fernandez-Ramirez.

“During that four hours, we’re mostly teaching them the basics of language. We’re not teaching them much in the way of analytical and critical thinking skills, so they really fall behind the rest of the students,” she says.

Linguistic Legislation

Superintendent Hoffman will be working to improve these scenarios as she take the helm this month. It will likely start with a push for passing S.B. 1014, a piece of legislation that would allow for as much flexibility in the SEI block as possible under the voter-approved constraints of English-only instruction. Last March, similar legislation won unanimous approval in the Arizona Senate Education Committee, but died without a vote on the Senate Floor.

S.B. 1014 was filed before the start of the January 14 Arizona Legislative Session and will likely get a rapid hearing says Geoff Esposito, an education advocate pushing for similar legislation.

“Since last year momentum has swung behind it, as its early filing and speedy committee hearing schedule shows. This small but necessary step will hopefully be just the beginning,” he says. “While flexibility will be critical in the short term, Superintendent Hoffman and other advocates have correctly identified that true progress cannot be made without the full repeal of Arizona’s English-only instruction law and discontinuing the mandatory SEI block entirely. The Superintendent has committed to making this a priority and to get a repeal referred to voters, but it’s in the legislature’s hands to make it happen.”

The proposed repeal aligns with UnidosUS own policy agenda. In November, it published a white paper titled Educational Fairness and Latino Success in Arizonawhich recommends repealing the state’s English-only law, discontinuing the SEI program, and creating and adopting native-language assessment programs.

Improving the Odds

As policymakers explore the options for changing curriculum standards, tens of thousands of ELs remain in their four-hour English-language blocks, facing that same 18% chance of graduating. So what can be done to improve these odds under the current SEI policies?

“Even in a four-hour block, there are innovative practices,” says Kate Wright, Deputy Associate Superintendent at the Arizona Department of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition (OELAS). “My biggest message to teachers who are working in an SEI classroom is to include content in all domains.”

Wright gave four examples of what that could look like:

- Project-Based Instructionallow for differentiation, collaboration, and hands-on demonstration of content knowledge in areas such as math, science, and social studies, all while focusing on the relevant academic language.

- Learning Stations: Usually used for differentiating topics and relevant language at the elementary level, these courses can be incorporated into any grade. They allow teachers to zero in on one thematic station at a time, from where they can provide more individualized instruction.

- Technology: Teachers can use computers and iPads to engage in activities such as blog writing and publishing programs, PowerPoint presentations, and online games that increase vocabulary while enhancing written and conversational skills.

Wright says this year the Arizona Department of Education hopes to develop an online and in-person collaborative teaching network for ideas sharing.

“Too often our EL teachers feel isolated. Through our Practitioners of ELs (PELL) meetings, OELAS Conference, and teacher summits we provide a platform for teachers to present innovative practices,” Wright says.

Arizona School Board Association Support and Training Specialist Nikkie Whaley would like to see that, but worries the state doesn’t have the resources to do it.

“Class sizes are big, and teachers are already stretched, so we might not have the budget to send our teachers to trainings and conferences,” she says.

Plus, she says low teacher salaries make it hard to attract the best, most innovative teachers willing to take the time to build more creative curriculums. Meanwhile, the teacher shortage is forcing school administrators to throw increased time and energy into supporting teachers with emergency or alternative certifications, detracting from resources that could be spent taking SEI instruction to a more varied and interactive level.

“If we don’t invest in our schools so that we can hire and attract highly qualified teachers into the profession, it will be more difficult to innovate and meet our students where they’re at. Without them, we can’t expect to see significant change in this or any of our other struggling populations,” says Whaley.