History in the Blind Spot: The Failure of Enforcement Policies in the Post-IIRIRA Era

The author would like to thank Charles Kamasaki and Cristobal Ramón for helping to develop this piece’s themes.

By Viktor Olah

In 1996, President Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) to “crack down on illegal immigration at the border, in the workplace, and in the criminal justice system” by strengthening the immigration enforcement apparatus. [1] While the IIRIRA provided the White House with a political victory on immigration, the law and subsequent enforcement efforts failed to meet these policy objectives[2], showing the limitations of this political-driven, hardline approach in addressing the country’s immigration challenges at the border.

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

The Responses to Increasing Migration to the U.S.-Mexico Border Between 1986 and 1996

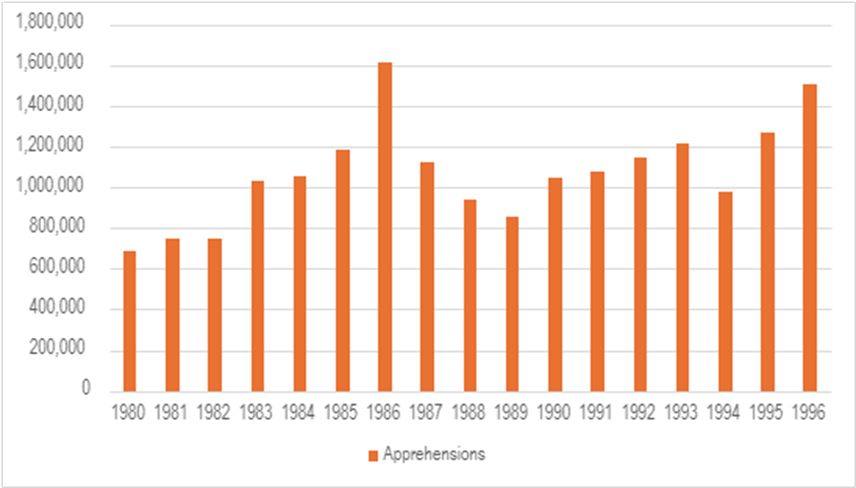

The history of U.S. immigration policy in the late 20th century saw lawmakers passing multiple reforms to the U.S. immigration system to address undocumented migration. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), which legalized long-term undocumented residents, also penalized hiring undocumented migrants to deter the increase of border arrivals between 1980 and 1985 that stemmed from reforms of the legal migration system in the late 1970s[3] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Southwest Border Apprehensions from 1980 to 1996

Source: CBP

The IRCA failed to meet its long-term goals. In addition to significant U.S. demand for foreign-born workers, the decline of the Mexican economy led Mexican nationals to leave for the United States in higher numbers. While Congress reformed the legal migration system in 1990, the shortage of visas to work and live in the United States incentivized more irregular migration. As a result, apprehensions resumed their increase in 1990 after dropping between 1987 and 1989 (Figure 1).

In response, the Clinton administration signed the IIRIRA in 1996. The law made it easier to deport non-citizens convicted of certain crimes and place individuals into expedited removal proceedings without judicial review. Undocumented immigrants residing in the U.S. for six months would need to leave the country for three years before applying for legal status, increasing to 10 years if they remain in the U.S. for more than a year.

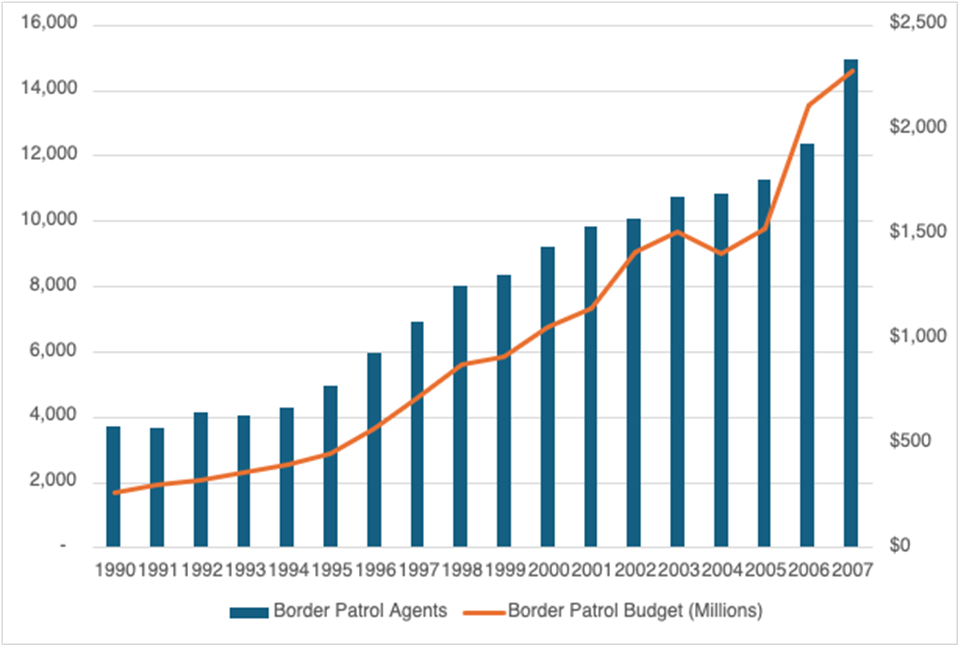

Congress also invested vast sums into the Border Patrol, the main enforcement arm of U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The agency’s funding grew from $263 million in 1990 to $2.2 billion in 2007, a nearly tenfold increase. Border agent numbers also increased from 3,715 to 14,923 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Border Patrol Agents and Annual Budget (1990-2007)

Source: CBP and American Immigration Council

Congress invested more into the enforcement apparatus after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 funded additional technologies to monitor the border and hired 10,000 new Border Patrol agents, doubling their number by 2010. The Secure Fence Act (2006) initiated the construction of 650 miles of fencing along the southwest border and surveillance cameras.[4]

The IIRIRA and Subsequent Enforcement Measures Failed to Meet Their Goals

Southwest border apprehensions data shows these measures did not reduce irregular migration, primarily due to the same factors that generated these flows in the early 1990s. Apprehensions at the southwest border increased from 1.3 million in 1997 to 1.6 million in 2000, with Mexicans consistently making up the vast majority of the apprehended population.

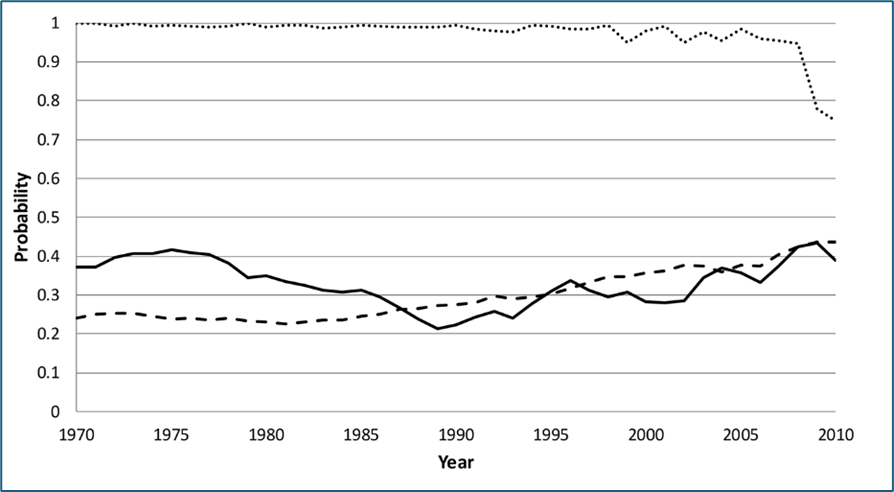

The rise in funding barely increased the chance of apprehension and only slightly lowered the chance of eventual entry into the country[5] as human smuggling operations grew in sophistication.

Figure 3: Observed Probabilities of Apprehension and Entry[6]

Note: Solid Line: Apprehension on first attempt; Dotted Line: Eventual entry; Dashed Line: Apprehension probability predicted by CBP budget

Source: American Journal of Sociology, 121(5), 1557-1600

These efforts also expanded the undocumented population by cutting off the circular migration that existed between the U.S. and Mexico. The growth in Border Patrol funding and the IIRIRA’s three and ten-year bars prompted more individuals to remain, increasing the number of undocumented migrants by 4.3 million in 2010.[7]

Demographics and Economics Influenced Apprehension Numbers After 2001

Migrant apprehensions at the Southwest border continued to increase through 2001. These numbers decreased significantly starting in 2001 due to economic and demographic factors that extended beyond the enforcement apparatus’ reach.[8]

First, U.S. job growth and increased use of work visas significantly impacted migration to the U.S.-Mexico border. Much like the post-IRCA period, apprehension numbers followed U.S. job growth through the 2000s. The increased use of temporary work visas by Mexican nationals during this period also corresponded with a drop in Mexican apprehension numbers, showing how legal pathways can impact this migration.

Figure 4: Southwest Border Apprehensions (millions) vs. Non-Farm Job Growth (millions) (1980-2007)

Source: CBP and Bureau of Labor Statistics

Studies show that demographic factors – not border enforcement – further reduced the number of Mexican nationals traveling to the U.S. Specifically, the population of young men, who traditionally formed a large portion of undocumented migrants entering the U.S., decreased heading into the 2000s, meaning fewer individuals traveled to the border.

The Policy Failures of the 1990s Continue to Reverberate in Today’s Immigration Debate.

The post-IIRIRA period of immigration policymaking remains relevant in today’s immigration debate. In the IIRIRA’s case, President Bill Clinton signed the law to project a “tough” position on immigration during a campaign year where irregular immigration to the border received increased public and political scrutiny. The broad support for this approach from both parties, which mirrored their backing for the era’s “tough on crime” policies, also shows its political appeal that remains firmly embedded in the current immigration debate.

While establishing a secure and orderly border is a valid policy goal, the failures of these politically driven measures show that hardline enforcement policies do not reduce migration to the border or the undocumented population. Instead, lawmakers need to expand legal pathways to the United States that provide a viable alternative to traveling to the border and legalize the undocumented population to leave behind the failed legacy of immigration policymaking in the 1990s.

[1] The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines irregular migration as “movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving country.”

[2] While there was no specific target for reducing apprehensions, the policies’ failure to decrease irregular migration and the likelihood of eventual entry at the Southwest border indicate a clear policy failure.

[3] A series of reforms of the Immigration and Nationality Act in the 1970s contributed to this increase in border arrivals. The INA’s 1965 reform marked the first restriction of migration from the Western Hemisphere, limiting entries to 120,000 per year. Laws passed in 1976, 1978, and 1980 took these restrictions on Latin American migration further, eventually making Latin American migrants subject to a worldwide cap of 270,000 resident visas. Given that U.S. authorities regularly issued more than 20,000 visas per year to Mexican nationals, these restrictions prompted more Mexican migrants and others from Latin America to cross the U.S.-Mexico border to live in the United States.

[4] Presidential administrations also adopted agency guidelines to make irregular crossings more punitive. In 2005, the Bush administration introduced Operation Streamline, which prosecuted irregular border crossers using a section of the Immigration and Nationality Act that allows authorities to punish an “improper entry” at U.S. borders with a 6-month prison sentence and attempted reentries with sentences reaching 20 years.

[5] DHS data on got aways illustrates this point. The term “got away” means an unlawful border crosser who— is directly or indirectly observed – making an unlawful entry into the United States and is not apprehended and not turned back. DHS data shows these numbers dropped from 1.1 million to 300,000 by 2012, largely due to due to demographics and 2008’s economic crisis decreasing demand for labor.

[6] The graph analyzes the observed probability of apprehension during the first attempt to cross the border and the observed odds of ultimately entering the country after repeated attempts. Additionally, the study used CBP’s budget to predict how it influenced apprehension probability. The exponential increase in border enforcement did not proportionately translate into higher apprehension probabilities.

[7] Expanded enforcement increased the deaths of undocumented migrants and the empowerment of organized crime by making smuggling a more lucrative option.

[8] The probability of apprehending individuals at the border did not increase significantly to act as a deterrent post-9/11. While apprehension numbers did decrease, the attack has impacted migration patterns by decreasing border arrivals due to the downturn in job growth acting as a pull factor and not through an increased probability of apprehending individuals.