What Makes Your Latino/Hispanic Experience Unique? ProgressReport.co Profiles Diverse Latinos from UnidosUS’s New ‘Voices’ Page for Hispanic Heritage Month. Here’s Part II.

Hispanic Heritage Month, which runs from September 15 to October 15, is a key time to consider what makes a person Latino, which, given the long history of migration to the Americas and the interaction with the Indigenous people who already lived there, can mean many things. UnidosUS has created a new website called Voices to understand and explore that identity, and since ProgressReport.co provides educational resources around that same subject, we decided to extrapolate. The following is a collection of the second three Latinx people who lent their voices to explain what makes them Hispanic or Latinx in their own unique way.

Elijah Romero

Age 14

Miami Beach, Florida

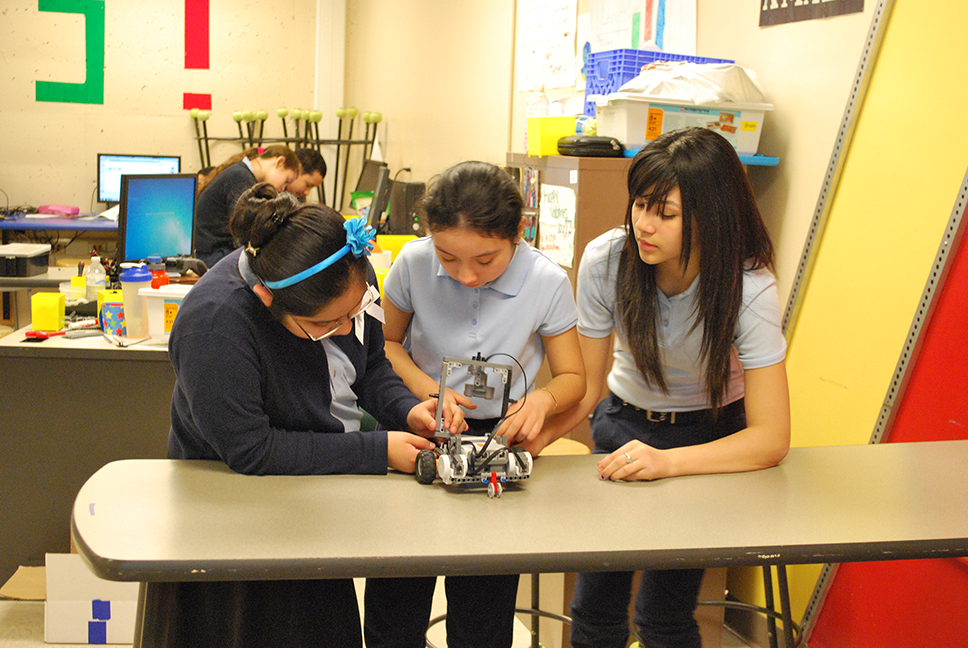

When ProgressReport.co met up with Elijah this fall to ask him about his Latino heritage, his answers were frank, brief, and also representative of a young person growing up in one of the most Hispanic parts of the United States. Asked what traditions he most likes about growing up in a Latino family, he said “barbeques.” But his family barbeques look quite different from the usual American cookouts of hotdogs and hamburgers.

His mother Evelyn Posada, a Colombian American, came of age in Miami at a time when the city was still very Cuban, but when many Argentinean and Colombian families were also seeking greater economic and political security in the United States. By the early 2000s, a few years before Elijah was born, Miami had become a virtual melting pot of all Latin American and Caribbean countries and that South American vibe was taking hold fast. Soon there were empanada stores in every neighborhood and yerba matte straws for sale at gas stations.

Elijah’s childhood is a little slice of all that. Both his mother Evelyn, her mother Angela Valdes, and his Argentinean uncles Juan and Alejandro Rozas, host barbeques with a skirt steak and some veggies, not to mention a steaming caldron of sancocho. And while tangos, a genre popular in both Argentina and Colombia—are occasionally played there, visitors are far more likely to get an earful of rock n’ roll. That’s because bands like the Rolling Stones represented resistance and rebellion during some of the South America’s darkest political years at the turn of the last century, and it inspired many Latino artists, including Juan, his brother Alejandro, and Evelyn’s sister Alexandra to grow their own rock ban, known as the Tremends.

But Elijah’s roots span even further. His father, Stan Romero, is the son of Mexican American school teacher Ray Romero who worked in hay mills in Wichita, Kansas, as a child and became one of the first Latinos in the NFL, playing for the Philadelphia Eagles, and his mother, Jodi Romero, is Irish American. When he goes to their house, the fare is typically Mexican.

While being Latino in Miami is nothing so unusual, Elijah says his classmates still sometimes confuse him for being an Anglo. “I always tell them no I’m Hispanic, and then I speak Spanish and they’re like ‘ah, okay,’” he says, noting how they quickly pick up on his not-so-gringo accent. And while he knows that being Latino in Miami is nothing so unusual, he is aware of how much work the United States has to do to spread respect and appreciation for all Latinos throughout the whole of society. “America needs diversity in order to be America. What would this country be without Hispanics?” Elijah asked.

Armando Manzanares

Age 46

Denver, Colorado

“We as a population are at the pinnacle of being recognized and acknowledged in American society,” civil rights advocate Armando Manzanares noted in his Voices video. “We are finally at all levels of society as far as opportunities—opportunities for businesses, opportunities for wealth generation, opportunities for home ownership, and that just continues to grow, so I feel 2021 is really a pinnacle time of pride and inspiration.”

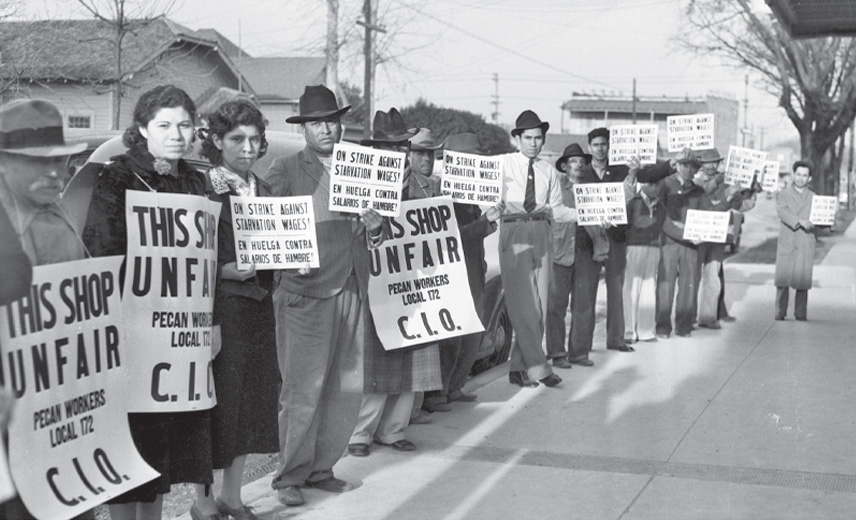

Armando is fourth-generation Mexican American and has plenty of reference points for this hopeful statement, precisely because he was born in the mid-1970s right at the height of a new era in Chicano/Latino activism.

“I was born during the medial point of the Chicano movement in the Southwest. My family was active in the movement and have first-hand experience with the fight and struggle for access, social change, and representation,” he explained to ProgressReport.co.

Because of the movement and the vision of activist leaders, his family became involved in the Crusade for Justice—a local activist organization championing Chicano civil rights and the Escuela Tlatelolco–the first of its kind charter school founded by legendary Chicano activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales.

“My family participated until the mid-1980s when the organizations were disbanded but continued to operate on the fringes until the 1990s. The whole experience of being part of the Crusade and the Escuela paved the path to social activism, cultural enlightenment, and societal representation—going and getting that seat at the table,” Manzanares said.

It’s thanks to this kind of advocacy and consciousness raising that Manzanares says gave him the self-determination to get a college degree and earn a middle-class living as a communications professional and entrepreneur.

It also paved the way for him to show up as his full self as a gay Chicano.

“Growing up, homosexuality was demonized by society, especially the Latino Catholic community,” he says. But the boundary pushers within his community have helped to shed some of the prejudice through education and art. “I weathered the experience by having a great support system of family and friends.”

And while he says finding your support system is key, he wants others to harness the civil rights achievements representatives of the Latino and LGBTQ community have been able to make, using them as a launch pad to take bold leaps without worrying what anyone else thinks or has to say.

“It does get better,” he assured. “I’ve always felt my objective is to bring representation to the American experience, representation of a Chicano that deconstructs people’s idea of a Latino and evolve their misguided and ignorant expectations of what it is to be Chicano/Latino in America,” Manzanares said. “I represent!”

Ariel Fernandez

Age 45

Miami, Florida

Ariel Fernandez always knew one of the biggest propellers of his interest in sound and rhythm came from his African roots, which are everywhere on his native island nation of Cuba. Born and raised in Havana, he began DJing as a teenager at a time when the city’s hip-hop scene was transforming that genre into something uniquely Afro-Caribbean and Latino, be it the beats they chose or the language in which they rapped. And like so many other parts of the world where hip hop has taken hold, Cuban artists were using it to assert their voices, to make their heritage, their identities, and their values known.

In 2005, Fernandez emigrated to New York to where he launched his own event production and DJ services company Asho Productions for a wide range of arts and culture institutions. There he would find others who could relate to his unique cultural, political, and racial experience.

“Since I consider myself Afro-Cuban, I identify myself as part of the Afro-Latino community. That’s a big movement in New York trying to make emphasis on the African presence in the Latino community,” he said in his Voices video.

For 10 years, he leveraged the Big Apple’s art and culture scene as a place for raising pride and social consciousness, often touring other cities as a DJ. One of his most popular residencies back in the day was an Afro-Cuban Funk night which he would host at an Ethiopian restaurant near the U Street Corridor of Washington, DC, a neighborhood that was a popular place of residence and performance for famous Black artists such as Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat King Cole. But his eclectic mix of funk, son, salsa, rumba, and jazz told an even more vibrant story about Black consciousness and solidarity through the entertainment industry.

In 2015, he relocated to South Florida where he founded a new artistic project alongside a large group of Cuban Americans and more recent Cuban emigres looking to connect their communities and their culture. Havana in Miami, as the project is called, helps Cuban artists promote their work while exchanging ideas with each other and engaging the broader public.

“Being a music promoter and a DJ, I think that’s one of the things I feel most proud of. There are the contributions of Latinos into the jazz scene in the 1950s and the creation of Latin jazz,” he said, noting that Afro-Latino artists such as Chano Pozo, Mario Bauza, and Tito Puente, all jammed with American jazz legends like Dizzy Gillespie, and Afro-Cuban singers La Lupe, Celia Cruz brought some of the biggest, boldest, and most emblematic voices to what came to know as salsa. “The big contributions they made to the music scene on this country that has changed for me the course of music forever,” said Fernandez.

–Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS senior web content manager and the managing editor of ProgressReport.co.