Welcoming Central American Students in a Historically Undiverse City

By Alma D. Velázquez, a fellow with UnidosUS’s National Institute of Latino School Leaders, and the assistant principal at Woodlawn PK-5 in Portland, Oregon.

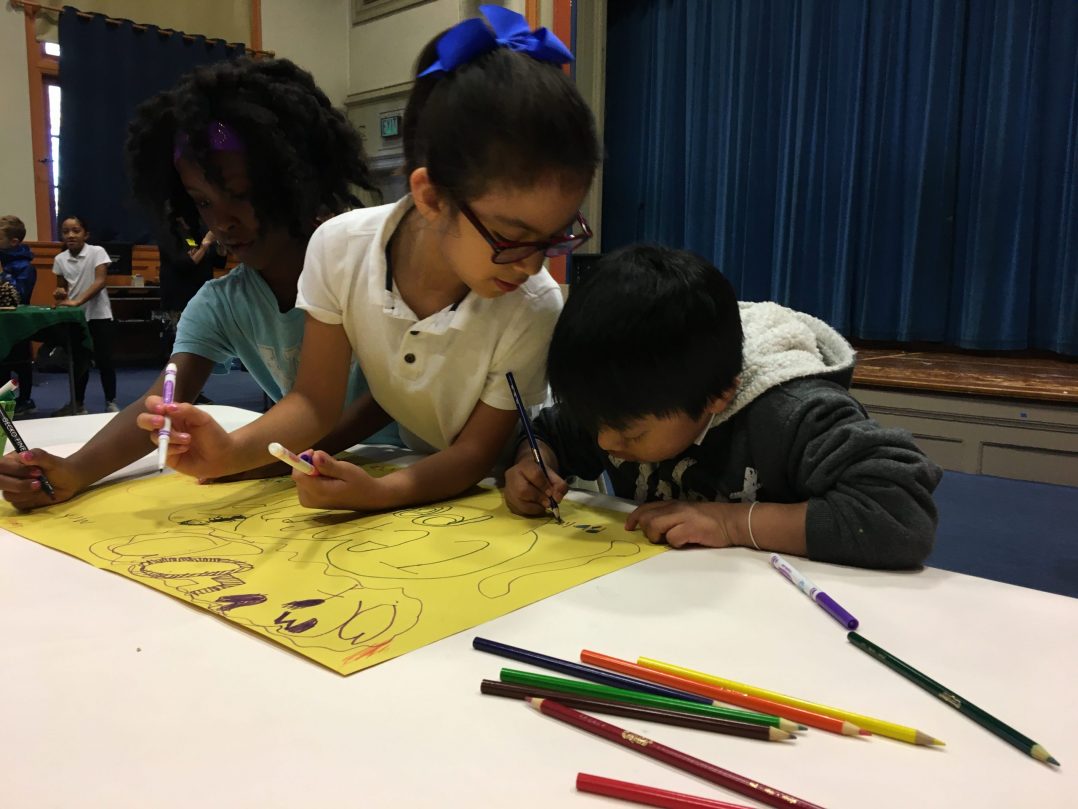

The girls came almost a year ago this spring, and their faces didn’t hide the anticipation, curiosity and perhaps a little fear about what was in store for them at our school.

Within a week, they each had a labeled cubby to their name, a lunch card in the cafeteria and the attention of their teachers and school staff who wanted to ensure they felt welcome and supported.

Like so many before them, Lupita and Ana arrived at the doors of an American school in search of a better life and escaping from a place of insecurity, even violence, and a clear lack of opportunity for those not already born into it.

They, along with their parents and two younger siblings, left western Guatemala to find a better future. It’s a well-known story. In fact, it’s a variation of my family’s immigrant story, as well as the stories of millions of people who have shaped this nation throughout its history. It’s a very American story.

At Woodlawn, close to the center of Portland, Oregon—often referred to as the “Whitest city in America”—the arrival of the girls last spring came as part of an influx of students from Central America, and it has meant an adjustment for the way we have traditionally served English learners (ELs), or what we refer to as emerging bilinguals, and even newcomer students. It required us to look for new resources—instructional materials, interpreters of Guatemalan languages, and adult education programs. We have connected parents to school transportation, clothing, jobs, food, and local community college options for adult English as a Second Language classes.

As a Latino school leader and an immigrant, it was imperative to me that our new students felt welcome and part of our community.

Targeting Supports to Meet Diverse Needs

In Portland and many other places across the nation, schools have become more Latino, more immigrant. In Oregon, now nearly 25% of all students are Latino according to the state’s Department of Education, an increase of 15,000 in the last four years, whereas the number of white students has gradually dropped by a little over that in the same time period.

Many have long thought of ELs as immigrants. But in fact, 75% of all ELs are were born in the United States, according to data gathered by UnidosUS.

That means that the remaining quarter of emergent bilinguals are therefore born elsewhere and immigrate into the United States, often as children. Since 2011, Portland schools have consistently received about 800 newcomer students each year from a variety of countries around the world—mostly from Latin America.

However, we believe that tougher (or inhumane, as some of us would argue) policies by the Trump administration have led to a significant drop in the number of these students so far this year. About half as many new arrivals have come to our schools as of the start of February. It remains to be seen if another few hundred will join us before the end of the school year.

With immigrant ELs, there is a great diversity of backgrounds, assets and needs. All of these factors influence the way in which schools must respond. We have begun by considering what and how we teach new our newcomers. And at Woodlawn, we’ve put a lot of emphasis in supporting the families.

These are some important moves that we believe help newcomer immigrant families get settled into our community:

- Connect families to resources for basic needs: At Woodlawn, many recent arrivals first moved into relatives’ homes in our neighborhood. As they found jobs—sometimes with the support and connections of our school’s family and community agent—they needed help to navigate the housing market, from language interpretation to knowledge of local housing options and resources for affordable housing.

- Help with food (and clothing) security: Our school’s food pantry, which takes place on a weekly basis, supports several recent arrivers with a free resource for healthy and diverse food options, including fresh vegetables, and staples like rice, canned soups, bread and sometimes meat. Our school’s uniform supply—many recycled from our own Lost and Found, as well as donations and our own purchases of items in high demand, have allowed us to give families a head start with clothing for their children when they first arrive.

- Ensure language supports for families need are readily available: Staff members should know who to call on for support to help families in their own language. At my school, I as the assistant principal as well as our school secretary, and a couple teachers, speak Spanish and can answer many questions from families. Our newcomer families most often speak Spanish, but for some, we’ve needed to locate Akateco speakers in the community to ensure we could interpret correctly during parent teacher conferences or when a student was injured.

- Collaborate with others to support beyond the most basic needs:Through parent surveys, families have requested help in signing up for adult English language classes, nutrition education, financial literacy for families, and more. This has meant reaching into community organizations and agencies to provide the best service possible.

- Create a space to hear their voices:We established Woodlawn Familias last year, a monthly Spanish-language parent group to ensure we were staying abreast of their needs. At the start of the year, this is where we support many parents in filling out the variety of forms needed for the school year, answer questions about school programs and practices, and where we’ve brought outside agencies for specialty presentations.

We know that when families are stable, students do better in school. To ensure our new students make progress from day one, we have worked to ensure our classroom instruction and language supports are strategic. We’ve consulted with our district’s English as a Second Language Department to ensure our newcomers received especially-designed instruction to quickly develop basic social and academic language in English. Whenever possible, we have assessed their academic skills in Spanish to ensure we were capturing more closely what they already know.

It’s clear that the way we work to serve our newcomers wouldn’t meet the needs of other emergent bilingual students in our schools. Students born or raised in the community, especially those in homes where siblings speak English, will have different language needs from newcomers.

For Lupita and Ana, settling into our community seems to be going well. Both girls are making quick progress in school and have a growing social group. Their younger siblings are either enrolled in preschool through Head Start or receiving home support from the federal program. Both their parents, who started in college careers in Guatemala, are enrolled in English as a Second Language courses at Portland Community College, where they plan to continue their education beyond language.

It’s exciting to see this family and others settle into our community and begin to thrive. We want to ensure that as a school we do everything we can to be a vehicle for that progress, and that we share our strategies with other educational leaders facing similar demographic changes in their schools and districts.