UnidosUS’s Annual Conference Offered Insights, Ideas for Closing the Gap from Pre-K Up Through College

During this month’s UnidosUS Annual Conference, dozens of small children ran around the UnidosUS National Latino Family Expo and dozens more teenagers poured into college prep and leadership workshops, reminding UnidosUS staff, Affiliate representatives, and other attendees that Latino youth are a big part of this nation’s future. In fact, data from the U.S. Department of Education shows Hispanic youth account for one-quarter of all K-12 public school students and that number will grow to one-third in the next decade.

Recognizing this trend, this year the UnidosUS education team offered three workshops focused on training, staffing, and funding for preschool, closing the K-12 achievement gap for underserved students, and ensuring Latinos not only enroll in college but finish their college degrees.

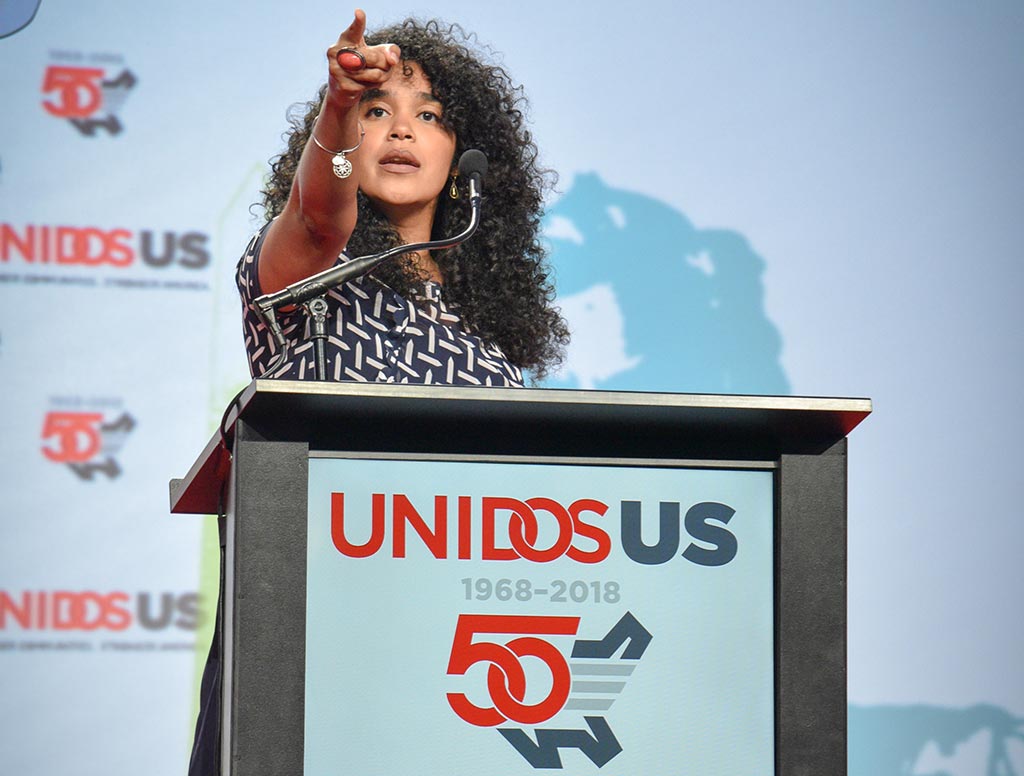

“Our students are the future workforce of America. We must support them,” Amalia Chamorro, UnidosUS Associate Director of Education Policy, tells workshop attendants.

Here is a summary of those three workshops:

What Do Increasing Educational Requirements Mean for Early Childhood Education Teachers?

Now more than ever, early education experts know that children deserve a solid emotional and cognitive foundation before they enter grade school. In order to improve learning outcomes, many states have begun requiring preschool teachers to obtain a bachelor’s degree, but that comes with its own challenges, for teachers and program administrators.

For instance, preschool salaries are often little more than minimum wage, making it hard for pre-K teachers who want to keep their jobs to pay for going back to school, and hard for college graduates to even consider teaching pre-K.

“Earning a degree to keep their position and maybe get a dollar raise doesn’t make sense. We have to figure out a different formula for compensating preschool teachers for the work they do,” said Robert Stechuk, Director of Early Childhood Education Programs at UnidosUS.

Relying on a panel of four Latino preschool teachers and a program administrator from UniddosUS’ affiliate organizations, Stechuk and his colleague Surabhi Jain, UnidosUS’s senior director of workforce development,opened a dialogue about the challenges and triumphs of how Latina teachers are responding to increased educational requirements. For instance, Maria Esparza, a lead preschool teacher at Inspire Development Centers in Washington, DC said it was hard to balance work, school, and family life.

“Getting my degree was like winning my dream, but I lost my husband,” she said. Attendants sat silently as they digested the news of her divorce, but erupted in loud applause when she talked about the gains of that degree. “He was self-centered. He didn’t want me to grow as a woman, but I’m glad I didn’t give up and that I pursued my degree. I came from a strong woman who gave me the courage not to give up.”

And having courage is something that all the panelists talked about imparting to their students – the courage to learn another language while maintaining and developing the one they learn at home; the courage to negotiate with their teachers what parameters they want for a positive learning environment; and the courage to come out of their homes for school amid fears of ICE raids and hate crimes often targeting Latinos.

“Social and emotional learning is one of the strongest things we can teach,” said Esparza, who says coursework in early childhood psychology reinforced her previous pre-K teaching experience. “I try to give them the strong sense of belonging they need. I greet them in the morning, I open my arms. If they want a hug, they’ll come. If not, then the good morning is there, but if I gain their trust- that makes me a stronger, more knowledgeable teacher,” she says.

Closing the K-12 Achievement Gap for Students of Color

That strong sense of belonging and identity will continue to be key to learning during the K-12 years noted public education champions Nancy Lewin, Executive Director of the Association of Latino Administrators and Superintendents (ALAS), and Richard Carranza, Chancellor of New York City Schools, during a workshop titled Closing the Achievement Gap for Students of Color. They said this could be greatly improved with better minority representation among school faculty and staff, and with greater psychological support for the current political climate.

The day before the panel, several dozen people were murdered in Dayton, Ohio and El Paso, Texas during mass shootings fueled by xenophobia and White supremacy.

“That’s the environment our kids are living in right now. We cannot be timid. We’re hurting,” said Carranza as he noted how a colleague had spent the night in a daycare center in El Paso comforting children whose parents hadn’t shown up to get them. “Were parents among the victims or are they so scared to pick them up?” He asked.

Carranza also underlined the importance of getting more minorities into teaching and leadership roles and of building out school curriculums to reflect the student populations they serve. He said this can help youth realize their full potential while curbing the practice of tracking wherein some students are encouraged to underachieve and others are encouraged to be more ambitious.

“If we believe that students are going to be successful, they will be successful. If we believe they can’t, they just can’t. We call it the pobrecito syndrome. That’s the kind of racism there is,” Carranza said.

“We can no longer afford for our students to be collateral damage,” added Lewin.

Lewin said she wants educators to take an assets-based approach to teaching underserved students by not just recognizing who they will become but what they come with when they arrive in any given space. She used her own personal story to illustrate, explaining that while working the fields with her farmworker parents, they would tell her to set goals and to envision her life as something more than what was in that moment.

“Education can change your trajectory, and it puts you in a situation where you can help others,” she said.

Carranza noted that the New York Department of Education took an assets-based approach to teaching terminology by replacing the term English Learners with Multilingual Learners because it reminds students, educators, and administrators that these students already speak a native language.

Toward the end of the panel, the two veteran educators reminded the audience that all of these approaches are tied to efforts to not only enhance education for underserved populations but align schools with federal civil rights laws.

“How we help you meet that bar is going to be different,” Carranza said, noting that education equality is not the same as education equity.

And to illustrate this, Lewin spoke of the challenges she faces of raising a son with Aspergers syndrome.

“As an educator, it’s hard to deal with his behaviors and his need to learn differently, but as a parent, it opened my world,” she said, noting that the situation has forced her to consider a realm of new methods for teaching and learning.

Carranza agreed. “Special ed is not a place. It’s a service.”

How First-First Generation College Students Beat the Odds

But getting through high school and enrolling in college is only part of the battle, noted panelists of a workshop titled The First-Gen College Journey. It was aimed at helping students finish their degrees in six years or less. Students in these circumstances may not have any close family member to guide them through the college process or they may be worried their starting salaries won’t compensate for the student loans they took out.

For panelist Daisy Gonzalez, Deputy Chancellor of the California Community College System, one way for colleges to address that is by really listening to their students’ needs. She said she led a panel of high ranking college administrators in the state of California last year and discovered a disconnect between what administrators thought students needed and what the students themselves said they needed.

“The first question we asked them was ‘why do you think your students enroll in your colleges?’” She said, noting that the officials were then given a number of options such as academic rigor and college ranking. None got the right answer.

“The number one option for students is to get a job,” Gonzalez said, noting that institutions across her state are trying to find the best way to ensure students a living wage within the first two years of college graduation. “In California, our economy is changing, and we want our students to be prepared for the jobs of the future.”

Making that happen will be different depending on where students live. However, they shared several ideas that could be helpful in a variety of places. One first-generation student mentioned the creation of an app that high school students could download to guide them through the entire college prep, application, and enrollment process. Several other panelists said they wanted to see funding for more college guidance counselors and support specialists who could help students navigate the myriad of challenges that sometimes prompt them to drop out. All of this, they said, would contribute to better educated, more well-rounded, and determined young professionals.

“It’s not only getting a degree,” explained panelist Maria Leonard, who coordinates internships in the Robert C. Vackar College of Business and Entrepreneurship at University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley.“It’s what’s your aptitude and your grades? You have to understand the market and industry needs. You need to know what our degrees are going to mean in terms in dollars and cents.”