Immigrant Rights, ELs, and Early Learning: UnidosUS’s Florida Affiliates Set their Educational Agenda

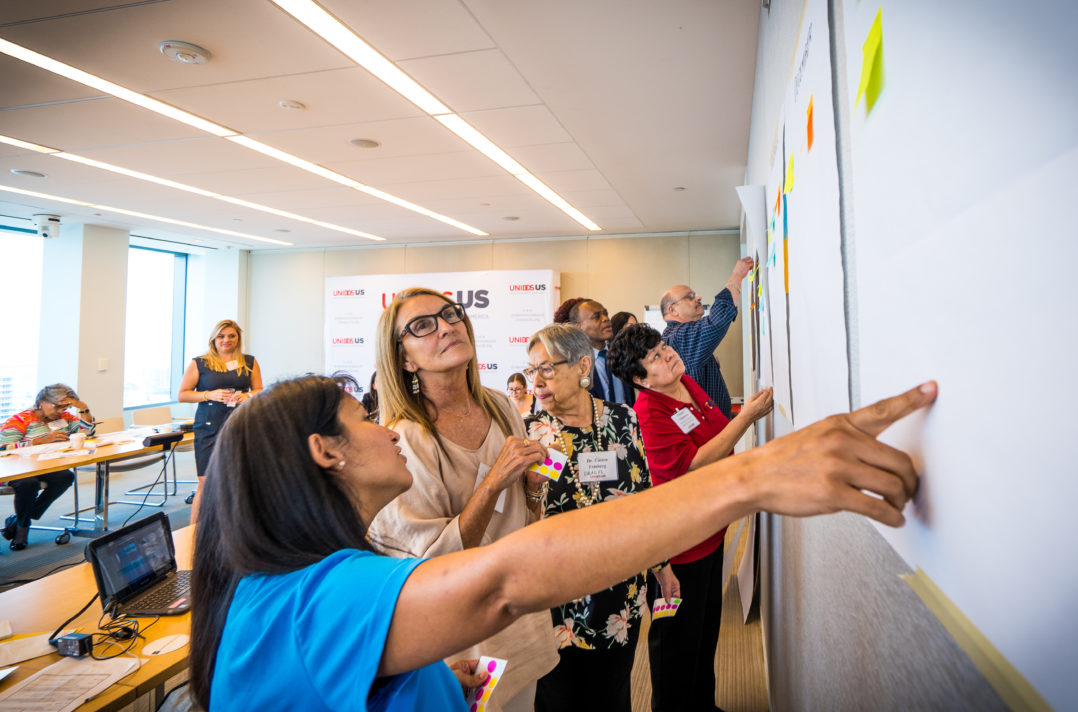

It’s a cliché, but it’s true: it takes a village to raise children. This month, participants of an UnidosUS workshop on the state of Florida’s health, education, and economy revealed how many different kinds of villagers contribute to that effort. That’s because education emerged as the predominant lever to engage UnidosUS Affiliates in research, outreach, communications, lobbying, and advocacy efforts, especially as it relates to immigrant families.

“It’s a moral imperative that we work together and support this community and each other’s work around it,” Florida Education Field Organizer Alejandra Rondon said, noting the group’s concerns about federal and state crackdowns on undocumented immigrants, and the impact those have on school children.

Dr. Rosa Feinberg Castro, Chair of Florida Media and Government Relations for the Hispanic civil rights group LULAC, agreed. “My sense is that the more times and the more different sources of requests that our policymakers get, the better it is. The more of us there are and the more organizations there are, the better off our children will be,” she said.

Hosted in downtown Miami, the program was to build momentum following an UnidosUS Florida Lobby Day last April. The lobby day took Affiliate representatives to the state legislature in Tallahassee to promote an UnidosUS-sponsored native language assessments bill for English learners and to ask legislators not to sign SB 168, a policy requiring local government and law enforcement to share information on all arrests with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The native language assessment bill is still on the table for the next legislative session, but SB168 ultimately passed, and it went into effect this month, just days before ICE began its nationwide raids.

Florida’s Implementation of the Every Student Succeeds Act

The timing of the ICE raids and the implementation of SB 168 may have shifted the original focus of the July event’s Florida education workshop, but it also highlighted UnidosUS’s broader educational mission of responding to the needs of vulnerable students.

Over the past several years, UnidosUS has been pushing the Florida legislature to revamp the way it collects and evaluates school data on vulnerable student populations. Those include children of color, students with disabilities, students who are low income, and ELs—all groups the Every Student Succeeds Act, the federal law governing K-12 education, requires states to track and accommodate to ensure learning opportunities for all school-age children. The native language assessments bill was introduced as a way to give educators a more accurate read on the content knowledge of students who are still in the process of learning English. UnidosUS will also be looking at ways to bolster early education to improve children’s entrance into the K-12 system.

With its close proximity to Latin America and the Caribbean, and its global reach through tourism, agriculture, and technology, Florida is a popular destination for immigrants seeking a better life or a boost to their careers. Not surprisingly, Florida has the third largest EL population in the country. They either arrived as speakers of another language, or were born in the United States but have a home language that is something other than English.

Getting these students college- and career-ready can be challenging if the state isn’t carefully tracking their academic progress across all subject matters, or assessing them according to their actual knowledge of a subject and not just their ability to test in that subject in English. In fact, UnidosUS is concerned that if the state only tests their knowledge of a subject in English, this will result in lower grade-level placement, remedial courses, and placement in special education services.

This worry is backed up by the data. According to the U.S. Department of Education, graduation rates among Florida’s ELs are 62%, compared to 82% among their non-EL peers.

UnidosUS believes that passing a native language assessment bill could help to close the achievement gap, especially since a 2018 fact sheet from the Immigration Policy Institute shows that 82% of all of the state’s ELs speak Spanish or Haitian Creole and seven out of 10 are U.S.-born.

“This makes it a lot easier to quickly produce native language tests,” says Jared Nordlund, UnidosUS Florida Senior Strategist.

Venezuelan immigrant mom Josie Ramos agrees. In fact, she wishes her own son, now 16, had the opportunity to test in Spanish when he enrolled in the Florida school system four years ago. She also noted how difficult it is for parents of ELs to keep their kids on track if they don’t have a wide array of supports.

“The logical thing is that if we’re in the U.S., we should learn to speak English, but that sounds very superficial and very easy. A 12-year-old isn’t like that. Beyond the economic part it’s the psychological and social part that they go through,” she explains. “We had to do things like hire tutors to facilitate the process, not just for them but for us as an entire family, for us as parents.”

She joined UnidosUS staff and Affiliates to lobby for the native language assessments bill in Tallahassee in April. She came to the workshop to underline the importance of getting stories like hers out to other EL families, the media, and policymakers.

“It’s so important that organizations like UnidosUS give continuity,” Ramos said. “Initiating a project like this is excellent, but it’s not just about starting it, it’s about maintaining it, consolidating it, so that it comes to fruition in real life.”

UnidosUS K-12 Policy Analyst Tania Valencia said she was grateful for Ramos’s testimony.

“As a teacher myself, I’ve seen what a difference it makes when teachers and parents get involved in their child’s education and it is a huge, huge difference that parents can make,” she said.

Getting the Word Out

Much of the rest of the Florida education workshop focused on ways to network between Affiliates and the communities they serve in order to better reach policymakers and the media. Attendees participated in a workshop on finding great characters for storytelling, mapping out a calendar of important events for advocacy purposes, and thinking of creative ways to engage children, parents, educators, and policymakers by hooking their campaigns around those dates.

“If you have a back-to-school drive where you have backpacks that you’re giving out, you could have a pamphlet for parents to read,” said Nordlund.

An example of this would be a packet informing parents of parent engagement programs, the native language assessment campaign, and a know-your-rights booklet to deal with topics such as immigration, bullying, and equal access to education for all schoolchildren.

Juliet San Juan, program director for UnidosUS Florida Affiliate Connect Familias, says that each October, her organization hosts a community baby shower for pregnant and new moms. This could be instrumental for identifying early education needs, as well as for considering the needs of older children these parents may already have.

“This is an opportunity to tell them about an opportunity—that there is an option to fight for something to see what we can get,” she said.

“You need parents? We have a bunch of parents that we screen,” said Josephine Mercado, founder and CEO of the Florida-based non-profit medical services organization Hispanic Health Initiatives.

For instance, perhaps a parent doesn’t have the time or doesn’t know how to engage the school or public health systems. Health is one of those topics that eventually prompt people to get out and seek help, so those screenings could be a place to talk about wider issues, such as their children’s education.

Empowering the Most Vulnerable to Use Their Stories to Make Change

Finally, what does it mean to be the voice for the voiceless? U.S. immigration policies are strict, but they are still varied, and so are the communities impacted by them.

In the state of Florida, it’s much easier for families from countries like Venezuela or Cuba to advocate for policy change in the Hispanic community because they are more likely to have obtained legal status. Cubans for years won residency through the Cuban American Adjustment Act, and Venezuelans have had better luck than many other nationalities in obtaining asylum because of the political crisis in their homeland. And because they’re more established, they may also wield more influence, participants noted.

“The growing number of Venezuelans in Florida are making them a political power bloc that make them influential on federal and state issues like education since many of their family members are dealing with the stress of navigating Florida’s school system,” noted Nordland.

During the storytelling portion of the training, participants considered who can and should do the talking for campaigns. For families that are undocumented, it might help to have a formerly undocumented person who now has legal status to offer testimony on their behalf. The use of digital media can also be helpful. For example, an undocumented parent or child might be able to speak out in a simple voice recording, and this, in turn, gives that person the sense that they can, in fact, be civically engaged even in times of great hostility.

Rondon noted that earlier this year, she traveled to Tennessee’s state legislature with a group that included young recipients of the Deferred Action Plan for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) for the Tennessee Educational Equity Coalition’s Annual Summit. These are youth whose parents brought them into the country without documentation when the youth were still underaged dependents. They have been fighting to maintain a special protected status that allows them to stay in the country to work and complete their studies. And while they fear this status could easily come to an end, they are already well-identified by immigration authorities, so they’re also in a special position to speak out for a wide array of student needs.

“It is so powerful to see students advocating for themselves,” Rondon said. “They’re so articulate. They know exactly what they want to convey. They know exactly what matters to them.”

Following that comment, participants discussed how they could better incorporate students into policy and advocacy workshops, as well as take them to lobby.

“It was evident from the energy and organizing that started to take shape that we are going to be a force to be reckoned with in advancing policies on behalf of the Hispanic community in Florida,” said Amalia Chamorro, Associate Director of Education Policy for UnidosUS.