Spotlight on Arizona: Navigating Back to School in a Coronavirus Hotspot

The voice of Lydia Isabel Palomares, mother of six-year-old English learner Valentina, breaks in frustration during a phone call with ProgressReport.co from her home in Tucson as she details her child’s first few weeks in a virtual first-grade classroom through Elvira Elementary. As the coronavirus pandemic drags on, Palomares knows remote classes are the safest option. In fact, going fully remote is one the many tough decisions Sunnyside School District chose to make for the safety of its faculty, staff, and students. In other parts of Arizona, reports of COVID infections began as soon as some schools opted to open their doors, forcing the facilities to close for as much as two weeks for cleaning and quarantine.

It’s a tense time for educational leaders as students alike, as school boards make decisions on how to resume class this fall, teachers advocate for their own health and safety, and parentsweigh the risks and benefits of sending their kids back to school. In any of the possiblescenarios, educational disruptions are constant, and they’re particularly hard on more vulnerable students, such as those who are low-income, children of color, students with disabilities, and English learners.

According to a 2020 UnidosUS fact sheet curating data from sources such as the Arizona Department of Education, the US Department of Education, and the US Census, there are some 75,000 English learners in Arizona – about 7% of the state’s K-12 population. Of those, 85% are Latino.

The state is an English-only state, meaning that even if teachers speak the native language of an EL student, they are not allowed to use it in the process of teaching them English. In 2000, the state passed Proposition 203, a law mandating that EL students be separated from their peers for a four-hour block of English instruction. That block was recently reduced to two hours, but advocates are trying to get the law repealed altogether.

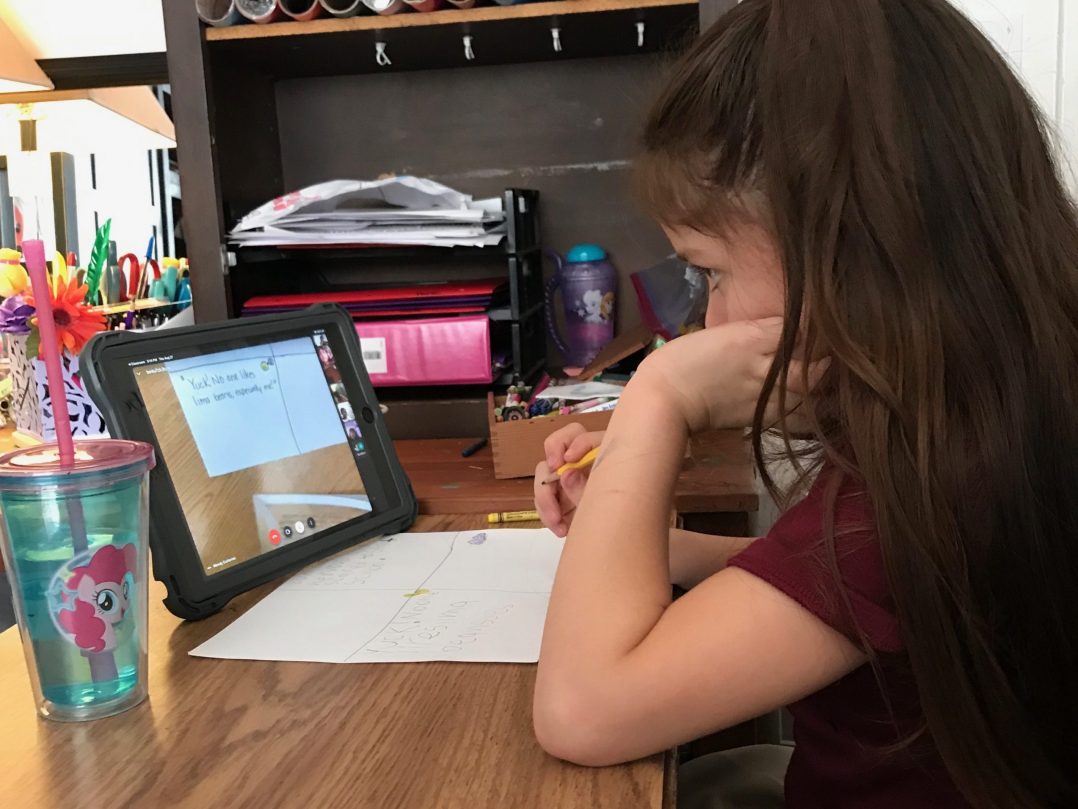

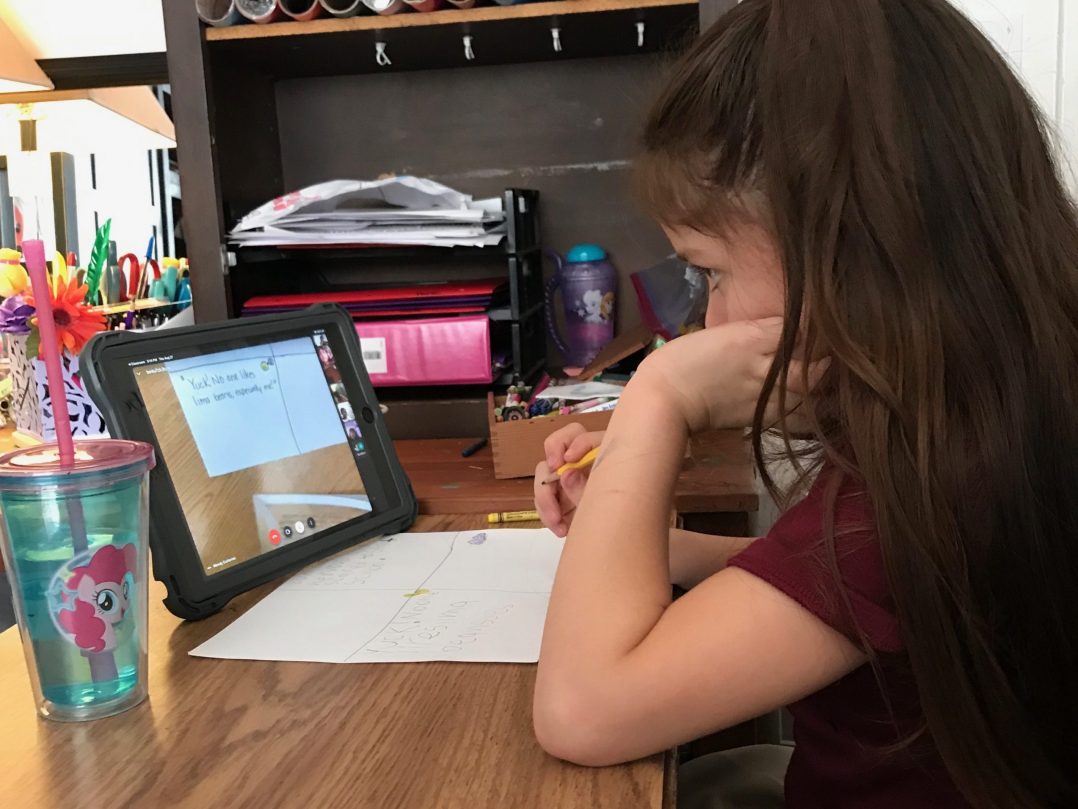

That’s just one of the factors that adds to Valentina’s EL challenges. On a computer screen, ELs struggle to hear and see their teachers as up close and personal as they would in a classroom, and it’s through that personal interaction that people often start to grasp a new language. On the flip side, teachers in a crowded virtual classroom may have a harder time noticing when a child looks lost or needs something repeated. Plus, language development actually taxes the brain and the physical body. But that’s also a likely side effect of any child trying to sit all day in a virtual learning environment.

“It’s really hard for the kids to sit there so many hours in front of the computer screen. Mine is on there working from 9 am to 3:30 pm, and by 1 pm she’s crying and saying “I can’t do it anymore. I’m tired,” lamented Palomares, who is a participant of the UnidosUS Padres Comprometidosparent engagement program, which is sponsored by UnidosUS Affiliate Amistades Inc.

Palomares says she’s noticed that other kids also get upset and tired around that same time, and it makes her wonder why online classes can’t be shortened to accommodate. She says she also wishes the school could provide more teachers so that schools can better simulate a more direct, in-person approach. And one other thing – she could use some tutors.

“I’m a single mom, and so to help my daughter, I had to quit my job at a vegetable market and move us in with my parents,” she said. “I have to sit with her for a lot of hours because she has lots of questions for me. I speak the language a bit but not perfectly, so when my daughter starts crying, I end up crying too.”

“The challenges of virtual learning put a magnifying glass on the issues of equity in our state. They were always there, but now we’re seeing these inequities play out in concrete ways and in real time,” says UnidosUS Arizona Policy Advisor, Elizabeth Salazar.

Valentina is lucky that her district gave all children laptops, and that the internet works pretty well at her grandparent’s house. In many cases, notes Salazar, low-income families don’t have that access to technology.

“They may have internet access through a cell phone, but that is in no way a pleasant or effective educational experience,” she adds.

A new study conducted in partnership with Alliance for Excellent Education (All4Ed), the National Indian Education Association (NIEA), the National Urban League, and UnidosUS— shows that nearly 17 million students across the country lack the high-speed internet access they need to adequately connect to the virtual classroom. The report comes with a call to action for Congress to pass the Emergency Education Connections Act, a bill aimed at closing that connectivity gap, and to include in its next coronavirus relief package some $6.8 billion for E-rate, a program of the Federal Communications Commission that provides discounts for telecommunications, internet access, and internal connections to eligible schools and libraries.

For Bernadette Saiz-Grijalva, another parent enrolled in the Amistades Inc. Padres Comprometidos program in Tucson, access to technology combined with a communicative school system has made all the difference. But unlike the Palomares family, the Saiz Grijalva family speaks fluent English, making it easier for her children to follow online instructions and for parents to assist with homework, not to mention advocate for their children in the school system. In fact, that advocacy is something she can help to do for all children through the Padres Comprometidos program.

“I have other parents that are in other districts saying ‘this is so awful,’” says Saiz-Grijalva, but notes that Elvira Elementary, the school where her nine-year-old daughter Maikayla and Palomares’s daughter Valentina are enrolled,has been quite communicative. Much of that came from the experience of trying to keep kids studying during the onset of the pandemic last spring and just getting large numbers of students up and running online for the new schoolyear, which began August 17th.

“At the beginning of this schoolyear, there were so many glitches because so many students were on the same webpage,” she says. “Now that things have been rolling along for about three weeks, It’s a lot smoother. The school has been very communicative with us. They’ve been, sending out weekly or biweekly letters just to inform us of what’s going on with what the Arizona Department of Health to figure when they’ll be letting the kids back into school or how long they’ll continuing with online learning. They’ve given us a large book of resources to help us out when we need it. So I’m pretty confident that the school is making good choices.”

And while there is still a teacher shortage, the school has been trying to keep students and educators energized by engaging them in block learning wherein students might see one teacher for math class and another for reading and writing. They’re also providing more opportunities for online physical education and for other physical breaks from the computer keyboard so that students have a chance to move and stretch out.

“I feel like it’s working,” says Saiz-Grijalva. “It’s actually been quite enjoyable.”

But many low-income families, don’t have the luxury of keeping their children home. That’s especially true for essential workers without the luxury of childcare. Not only does a return to school heighten the children’s chances of infection, it can lead to more exposures when those children come home at the end of the day.

“The current health and economic challenges brought on by COVID-19 are disproportionately affecting Latinos. Of the cases where ethnicity is known, Latinos make up 46% of COVID-19 cases in Arizona,” reported a recent UnidosUS poll looking at the economic impact of the pandemic on the Latino populations of Arizona, Texas, and Florida. “Fifty percent of the Latinos we polled had difficulty buying everyday necessities and 40% had to access local food banks. There is no denying that our community has been devastated in the last six months and we’ll spend years rebuilding our economic power in the wake of this global pandemic.”

And while COVID may seem like the most obvious threat to children’s safety, Salazar can name a few more where the pandemic could have long-term consequences to children’s physical, mental health, as week as their academic growth and development. For example, low-income students who aren’t attending a physical school may have a harder time obtaining subsidized meals – usually breakfast and lunch. Their academic and social skills may be hindered by the fact that they can’t interact with each other in a physical classroom or out playing on a playground. Salazar further underscored some less obvious issues that will arise from the pandemic, for example students’ face to face interaction with mandated reporters like educators and social workers. Without in person interaction, staff are less able to identify and treat issues like anxiety or depression, not to mention track potential child abuse.

Through the Padres Comprometidosprogram and broader community outreach efforts, Amistades Inc and other UnidosUS Affiliates are working to help families deal with these circumstances. For example, they’re providing meals for students who may be food insecure at home, and they’re available by phone, email, ZOOM conferencing and a few socially distanced gathering to troubleshoot on homework, issues with technology and online, learning, as well as the children’s social and emotional well-being.

“Parents definitely know that we’re a resource. They can use us as an opportunity for them to gather and to share ideas and solutions, and for them to view each other, as parents, as resources and support system,” says Amistades Inc. Senior Project Manager Melissa Gomez. “If they’re worried about sending their kids home from school because they don’t have the funds to provide them lunch or snacks, we have those resources available. When it comes to virtual learning, if they need additional support, we can provide some assistance in showing them the steps and what different online websites that they can use to help with homework. If they can prove that they need funds for childcare, we can help with that as well.”

Salazar says these community programs are vital lifelines, but we also need local, state, and federal policymakers to work proactively, show leadership, and advocate for their constituents.

“COVID-19 has no hard and fast expiration date. We’ll be dealing with the fallout from this for years,” she notes. “The state of Arizona is one of the most underfunded public K-12 systems in the nation and we will need significant investments to ensure all students can succeed in a safe and effective learning environment, whether it’s online, in-person, or hybrid.”