Researchers at University of Miami Create a Data Visualization Project to Increase Support for Local English Learners

Florida’s constitution declares English the state’s official language, but that’s hardly the practice when it comes to Miami-Dade County. U.S. Census data shows about 77% of the county speaks a different language at home, and 43% say they speak English “less than well.”

While many Miamians successfully glide through their days without uttering more than a sentence in English, education advocates say English proficiency is a must for any student who wants to succeed in the world outside of South Florida or help South Florida stay connected to the rest of the United States and the world outside Latin America.

With that in mind, three staff members from University of Miami’s Office of Institutional Research formed a team called the Visualiz-IRs to create a data visualization story using public data from the Florida Department of Education and the National Center for Education. The project reflects the experiences of English Learners (ELs) enrolled in Miami-Dade County schools and compares the performance of these students with their native English-speaking classmates.

In November, the team won the 2018 VizUM Visualization Competition organized by the UM Center for Computational Science at the 2018 VizUM Symposium, a competition aimed at encouraging students, scholars, and professionals of all disciplines to design static or exploratory data visualizations based on publicly available data about Miami-Dade County.

Data visualizations make information easier to understand

“Letting the user interact with visualizations is an easier way for people to access data,” says Visualiz-IRs co-creator Caroline Seguin. “A lot of state or county data is made public but is difficult to access and is in a format that is hard to read and to use. For example, data in very large tables can take a long time to download. Translating this data into a visual and interactive format makes it a lot more accessible to everyone, and therefore more likely to be used in policy and decision-making.”

UnidosUS’s education team welcomes user-friendly visualizations like these. In fact, they invited Seguin and her team members, Shirley Lowe and Jie Huang, to showcase their data visualization project this month alongside an UnidosUS white paper presentation titled Educational Fairness and Latino Student Success in Florida.

Data visualizations can help tell a story

UnidosUS Florida Education Organizer Alejandra Rondon believes visualizations hold tremendous promise as a storytelling tool for education advocacy.

“I am impressed with the Visualiz-IRs team and how they worked so thoughtfully and creatively under the auspices of the dedicated VizUM Competition organizers to learn and hone their visualization skills so folks can have a better understanding of English learners in Miami Dade County Schools,” she says.

The Visualiz-IRs story explores achievement gaps by looking at high school graduation rates and results of the Florida Standard Achievement tests in math and English. It also looks at how the gap varies with other variables such as school type, gender, and economic status. The data and analysis can be accessed by clicking on the 10 story points which address the following questions:

- Who are ELs?

- Where are ELs in Florida?

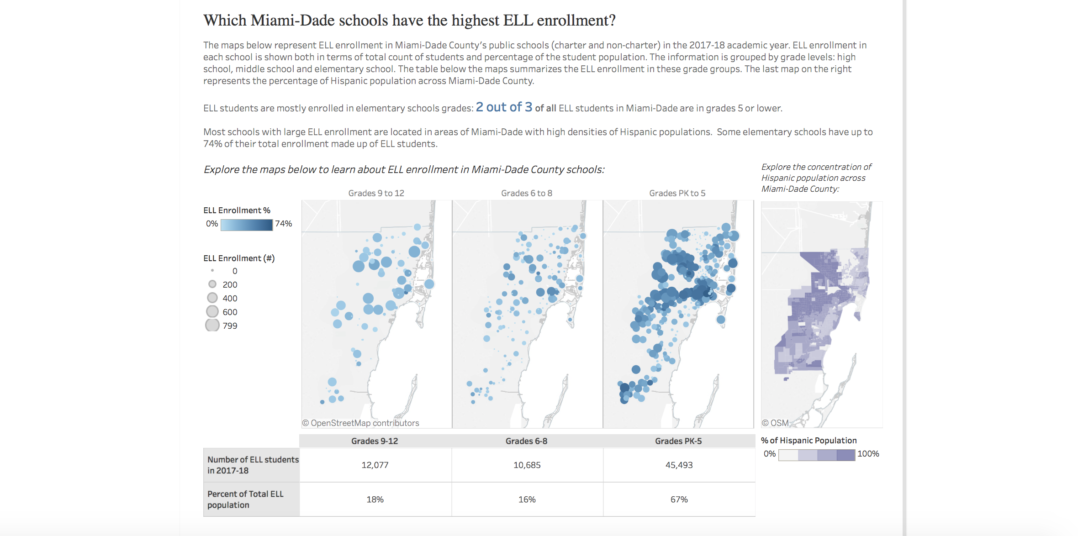

- Which Miami-Dade schools have the highest EL enrollment?

- How did EL enrollment vary since 2013, in individual grade levels?

- How does EL enrollment vary between charter and non-charter schools?

- How does high school graduation rate vary between EL and non-EL students?

- How do Florida Standard Assessments (FSA) results compare between EL and non-EL students?

- How does the achievement gap in FSA vary across other variables?

- A historic timeline of legislation impacting EL students

- A list of organizations that help and advocate for ELs

The Visualiz-IRs say they were particularly alarmed at the low levels of English language achievement among high school students. About 77% of ninthgraders learning English were ranking in the lowest level of achievement, compared to just 20% among elementary students.

The team worries that students in the upper grades won’t be able to live up to their full potential as they leave school.

“One in five students in Miami Dade County is an English Learner, and you want to make sure this population succeeds because they’re the future,” says Seguin. “The more they succeed, the more opportunities they will have.”

How long a student remains at each level remains a missing piece of the puzzle

During the creation of the project, the team discovered that the Florida Department of Education was either not collecting or not publishing a lot of seemingly crucial data.

The Visualiz-IRs understood the department was bound with some student privacy constraints. However, they say it would be helpful to know how long students are staying in an assessment level. Plus, were also unable find information on teachers, ESOL teaching methods used in the schools, and information on when these ELs had arrived to the area.

Having access to data like this would make it easier for education advocates to make recommendations to policymakers. That could lead to more funding in the areas of greatest need. Plus, having information on students’ immigration status would paint a better picture of how long it takes an EL student to leave the program with an advanced level of proficiency.

The Visualiz-IRs understand the difficulties of being an EL on a personal level

The Visualiz-IRs say their own experiences learning English give them a vested interest in growing and promoting this story. Seguin is a French Canadian who learned English as a second language in Montreal. Lowe, who hails from Jamaica, learned Chinese with her immigrant parents at home and English in the Jamaican school system. And, like many of Miami Dade’s high-school level EL’s, Huang struggled with learning English later in life.

Huang started learning English after following her husband to the United States. Not long after, she enrolled in a marine science master’s program and struggled to follow class lectures or participate in in-depth discussions.

“Improving English levels isn’t something that can happen in a short time,” she notes. “High school EL students need to spend double or even triple the time and effort on their course studies to keep up with their non-EL classmates.”

It’s a daunting task, but she and the other Visualiz-IRs hope their project can help raise awareness and support.

“We want the people in charge of high school education to see this gap and to do something to help students facing these kinds of situations,” says Huang.