Q&A: Texas Artist Hakeem Adewumi’s Juneteenth House Gallery Project Helps a Diverse Public Reflect On and Celebrate This New Federal Holiday

The history of when slavery in America officially ended is a complicated one. Some would say it never has. But for two centuries, many Black Americans have marked June 19, 1865 as one of the biggest milestones in their struggle for freedom. While slavery in the United States was officially abolished in 1863, it continued to be a practice in Texas until 1865. That’s when some 2,000 Union troops under the direction of U.S. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger marched into Galveston, Texas to announce that more than 250,000 Black people enslaved in that state would were officially free by executive decree.

The event would become known, especially in Black communities as Juneteenth. And while it is sometimes taught in schools, public awareness of its significance only recently began to grow, largely from concerns about ongoing oppression against Black lives. Rather than look at it as a simple freedom celebration, many civil rights activists believe it can be harnessed to discuss the extensive racial justice work that is yet to be done. Recognizing these public discussions, this week the U.S. Congress voted to make Juneteenth—an event Black writers, historians, and artists have spent decades working to document—a federal holiday. President Biden signed it into law on Thursday afternoon.

Meanwhile in Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott just signed a bill banning the teaching of critical race theory in public K-12 schools, making it harder for educators to engage students in an in-depth discussion of racial justice. But some artists in the community are using their aesthetic projects to do just that for the general public.

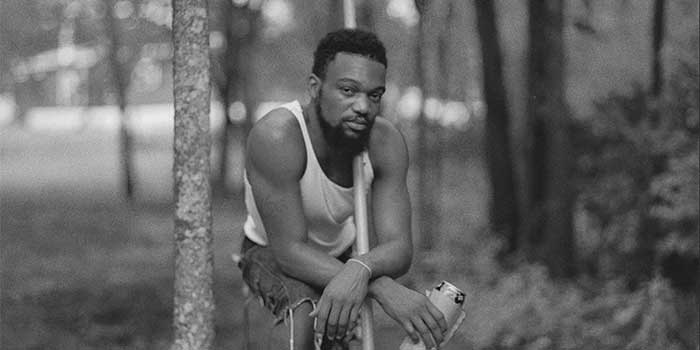

Hakeem Adewumi, a Dallas-based artist whose Black family’s roots in Texas reach back generations, recently created a mixed media art installation called the Juneteenth House Gallery to help diverse members of the public learn about and better relate to the area’s Black history. His is a series of archival images mixed with newer, modern interpretations of the Black experience throughout history as a way of underscoring intergenerational connections, geographical imagination, and memory. ProgressReport.co Consultant and Historian William Garcia-Medina, a doctoral student of American Studies, and a longtime friend of Adewumi, recently sat down to learn more about the artist’s project. —ProgressReport.co

Q: In your own words, what is Juneteenth?

A: I’ve been thinking more about Juneteenth as a sort of embodiment, a concept, or something like a holiday. History books and media have taught us how Juneteenth was made. However, Juneteenth has been reduced to the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln, and General Granger. Those are the political features conceptualizing freedom, but I don’t really consider them the architect of that burden of freedom. I consider the enslaved and formerly enslaved folks who made a claim to their own freedom the architects of Juneteenth. I’m using this concept to explore those Black cultural things that were created in Texas out of the racial terror that was present. But also, all the nuances of what it means to be Black in the afterlife of slavery. What I’m finding is that there are other versions of Juneteenth across the African diaspora and across the United States. In those other countries it’s not called Juneteenth, but ideas around emancipation exist in South America, Central America, and the African continent.

Q: Last February, Martin Luther King Jr. III – Rev. Dr. King’s eldest son—traveled to Mexico and spoke of how a lot of Black Americans went there during the Underground Railroad. People talk about Canada, but it didn’t make sense for a Black person in Texas to go to Canada, when you could just go to Mexico. He also spoke on behalf of Afro- Mexicans and their history, which includes Black people who came there enslaved by the Spaniards but also including other Black migrants from the Caribbean and the African continent who are also currently migrating to Mexico. For you, do stories like this feed into Juneteenth?

A: Juneteenth means a moment of recollection— the work of memory. The past isn’t really the past, and neither is the present. Therefore, I see Juneteenth as a portal. I think about my grandparents and their parents and how their emotional experiences, and their livelihoods define Juneteenth. For me, Juneteenth is very personal. My family is here, and the actual places where my mother and my grandmother grew up mean something. So, how do we preserve these places? Memory, recollection, and preservation

Q: Until recently, there hasn’t much of a national conversation around Juneteenth, so I’m interested in knowing how you learned about it.

A: I was probably watching PBS (laughs). As a child, we didn’t really celebrate it growing up in my family. We were definitely big Fourth of July people, and I have warm memories of it that include fireworks, barbecues, and families getting together at my grandmother’s house. I probably didn’t recognize and explore Juneteenth until I got to college or even after college. I mean, I knew about it since middle school, but I just didn’t know what it meant.

Q: Tell us about your Juneteenth House Gallery Project. I understand you relied heavily on archival information and photos from the Federal Writers Project, in which the U.S. government employed historians, teachers, writers, and librarians to develop what became known as the American Guide Book Series to teach the American public about its many communities.

A: The final episode in my exhibit, “Behold the People, Evidence of Being Not Seen,” is taken from part of a scripture in Hebrews 11 in the Bible. It’s a scripture that I think a lot of Black folks in the South or Black folks in general in America reference.

“Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see. This is what the ancients were commended for,” it reads.

But what I was really trying to investigate and interrogate in the bodies of work, and eventually, what I wanted to talk about with the Juneteenth House was using the Federal Writers Project as a source for story. And of course, understanding the interior life of the Black enslaved folks who actually made and founded Juneteenth.

They’re officially the ones who created this concept of Juneteenth. It’s this concept of freedom after enslavement, and we know that freedom after enslavement was very violent. We know that the KKK had information and insurgencies around that same time. A new form of racial terror was formalized around free Black communities. Although we may not have been living on plantations and working on plantations for slave masters, there was still racial terror. In some cases, worse than slave plantations.

I really wanted to comb through the narrative that we were not given in school. You see, the Federal Writers leave many nuances and details unfinished from the record. Those who are scholars of Black studies or folks who have lived in the topography and witnessed the predatory way White folks celebrate Black people. They can tell you that many of the stories from that project— at least the ones we know of—aren’t complete.

Q: So you’re saying some of those stories have been removed, altered, or covered up?

A: That and Black people would oftentimes exaggerate or gloss over something, or they may come up with a lie about something because they didn’t want to be excluded from the historic record. It’s the only kind of record that we have, and I feel like this is the truth. Sometimes it’s the way that we recollect, dream, and imagine.

Q: So a couple of examples of that would be Zora Neale Hurston, the first Black anthropologist who wrote in both ethnographic and novel form. She was one of those Federal Writers, and she would go on to write many stories about Black folks in the South. Some have questioned whether her ethnographic work was entirely accurate, while others believe she was sometimes silenced because she was a Black woman writer and because she often let her sources speak in a vernacular that was hard for standard English readers to understand.

A: Even the portraits taken during from the Federal Writers Project excluded lived experiences, and reducing people to their bodies instead of trying to imagine what those lives were like. That’s potentially what I did. I layered the actual takes on the photographs and made visual work with that. For my portrait archive, I invited some friends and folks in my community to stage those portraits in order to underscore embodiment of what it means to be a Black Texan and talk about intergenerational connections for Black people in America.

There’s also a lot of strong African ancestry and spirituality, and all those things that we’re coming to know. Juneteenth also is part of that cannon because of police brutality and racial terror in America now. There’s a strong connection and move toward these archives and stories so for me, Juneteenth House is a way to vocalize and imagine what those stories were like in the places that I grew up. What this work really does is to juxtapose the Federal Writers Project with the photographs that I restage, iterate, and imagine.

Q: A lot of White folks say, “well, you know slavery was so long ago.” Not only does that obviously dismiss the intergenerational knowledge, it also tries to cut off intergenerational relationships. I also noticed in the Juneteenth House Gallery project that you place photographs side by side next to archival ones based on different time periods. I’m assuming that’s to show this intergenerational connection.

A: I was leaning towards the art of juxtaposition to highlight the obvious contrast but also referencing a lot of the emotional labor that was capturing the Midwest. I really wanted to mirror the haunting from the Federal Writer’s Project by placing the photos side by side. Most of the photos were from my own archive taken between the years of 2012 to 2020, and the Federal Writers Project photos from 1936 to 1939, but they have a considerable generational gap. Most of the folks who were photographed in the 1930s were probably born in the late 1800s. A lot of them were children when Juneteenth actually came around, so I started looking at my archive and looking back at the Federal Writers Project. I was seeing some very similar poses that I think also carry a lot of the emotional similarities that I want to talk about. I push the emotional labor of this work by inviting friends to redo the stories with me while trying to evoke the history of that recollection.

Q: What do you hope people will get out of the Juneteenth House Gallery Project?

A: I just want folks to refit this concept of love. There’s a fine line I’m trying to massage out of the work. There’s a kind of work I want to create for this topic but I don’t want to be over- indulgent with the concept of slavery. I’m really referencing a lot more folklore. I think folklore is a form of truth that is never written within the record. I still think we can tell truthful stories about Juneteenth, especially after revealing the stories of older Black folks. This project is changing and learning, so I still don’t have the full language for it, but I want folks to go on this journey with me. I want to work with folks who may have more information than I do.

For more on Adewumi’s work check out http://www.hakeemadewumi.co.

Garcia-Medina is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of American Studies at the University of Kansas. In 2016, Garcia-Medina earned an MA in Curriculum and Instruction from Teachers College–Columbia University in New York City. He also has an BA and MA in history from the University of Puerto Rico-Recinto de Río Piedras. Garcia-Medina is a contributor for Latino Rebels since 2015 and has made appearances on Latino USA and NPR. He tweets from @afrolatinoed.