Multimedia: UnidosUS’s Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellows Tackle Policy

This past year, UnidosUS launched its first-ever Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship. The program is geared to first-generation students pursuing their undergraduate, graduate, or doctoral degrees and recent college graduates who identify as Afro-Latinx and are passionate about racial equity and making meaningful change in their campus community, workplace, and beyond. The following multimedia report is a synopsis of that program.

History books and Hollywood movies have rarely acknowledged or depicted Black people as Latinx, or Latinx people as Black. And yet, people identifying as both have been living in this hemisphere since the onset of colonization and the colossal transatlantic slave trade. Today, data from the Pew Research Center suggest that people identifying as Afro-Latinx account for an estimated one-quarter of the overall U.S. Latinx population. Like many people in underserved communities, structural racism, unconscious bias, and outright prejudice can obstruct their pathway to success.

With that in mind, UnidosUS built an Afro-Latinx-specific leadership training pilot program out of a preexisting program, the Líderes Avanzando Fellowship. The first-ever Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship kicked off its nine-month program online last August with 12 undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral students, as well recent graduates, all of whom identify as both Afro-Latinx and the first in their family to attend college. Broken into three-month modules, the program was designed to create a safe space for Afro-Latinx to explore their individual and collective experiences and to develop memos and presentations on federal education and health policies that could lead to lasting change in their communities.

“This is the first national fellowship of its kind, centering the intersectionality of being Black and Latinx. Our fellows bring perspectives that bridge our communities and present innovative policy solutions that will more equitably shape the future of our country,” notes UnidosUS Education Leadership Program Manager Washington Navarrete, who headed up the fellowship.

TRAINING MODULE I: Mapping the Racial Equity Landscape

During their initial orientation, each participant was asked to identify and interview three Afro-Latinx anywhere in the country to gather a broader understanding of the needs and challenges faced by the larger Afro-Latinx community. From there, the first module launched with an overview of how U.S. state and federal policymaking work, a racial equity landscape analysis, and a briefing on what UnidosUS is currently doing to advocate for policies they believe will best support U.S. Latinos.

“It’s really about getting to know the landscape around what is happening and understanding the system. How does policy work? Who are the people? Who’s in leadership? But it’s also about the self, exploring their identities, who they are, and what kind of leaders they want to be,” says Navarrete.

Halfway through that first module, participants were asked to identify which issues were of greatest importance to them and then to speak to other participants to decide which issue they would like to advocate for and with whom. With this information, UnidosUS program leaders divided the group into teams of two or three people and assigned each team the policy issue that best represented their interests.

TRAINING MODULE II: Reunion, Reflection, Rehearsal

In an effort to bring the group together in a place representative of the participants, UnidosUS chose to host Module II in Miami, a city known for having a large Black, Latinx, and Caribbean population. Their first stop was a dinner at the Black-owned restaurant Red Rooster in Overtown, a neighborhood that, during segregation, had been called Colored Town. Over the following two days, participants gathered at the IPC ArtSpace in Miami’s Little Haiti Cultural Complex. In these locations they further developed their policy memos and corresponding presentations, they delved deeper into how their identities compare or contrast with other Black and Latinx experiences.

“Miami’s so vibrant. There’s so many colors, there’s so many people that look like me, and I feel like that is what Panama felt and feels like for me when I go back,” Emily Gardin Ríos, an Afro-Panamanian, said during the event.

Líderes Avanzando Fellow Annette Raveneau, a former resident of Miami Beach and Afro-Panamanian, said the setting made her feel emotional as well. Her family emigrated from Panama to Miami when she was a child, so this was the city where she came of age and went on to spend many years working as a television reporter. She noted that the Black-owned venues UnidosUS had chosen represented an effort by people of African and Latinx descent to hold on to and showcase historic spaces in their communities, but she felt conflicted about the hordes of tourists passing through these largely Black, low-income neighborhoods that outsiders used to make an effort to avoid.

“I’m trying to figure out my feelings so there’s a lot of journaling that I need to do after I leave Miami,” she told ProgressReport.co.

Local Afro-Puerto Rican community organizer Ayari Aguayo synthesized observations like these in a talk she gave to the fellows about advocating for diversity, equity, and inclusion in a state where business leaders and policymakers often push back on the needs and interests of an increasingly diverse population.

One such example was Florida’s controversial HB 1577 Parental Rights in Education bill, which ultimately passed in early March. Because it bars teachers from discussing LGBTQ topics parents might deem inappropriate for some ages, critics have coined it the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. UnidosUS has taken a stance against this legislation. In a state with such a large Latinx student population, the organization fears the bill will harm students who identify as both LGBTQ and Latinx.

“Whenever these bills come up, we start to question who we are, we start to wonder, are we good enough?” says Aguayo, who also identifies as queer.

Aguayo now serves as the leader of community engagement and belonging for South Florida’s YES Institute, which strives to prevent suicide and other forms of violence and to ensure healthy youth development, including communication and education on gender and orientation. According to data from her organization, suicide is now the second leading cause of death among South Florida youth. Those identifying as LGBTQ or who feel unsure of their orientation are 3.5 times more likely to commit suicide, while suicide rates are six times higher than that for transgender youth.

Recognizing that the Afro-Latinx fellows understand how hard it is to come from any underrepresented or oppressed group—and harder still when one’s identity intersects with more than one such group—Aguayo offered a piece of wisdom she often shares with the YES Initiative youth. She tells them to start their own self-advocacy with questions such as, “What brings you joy? What brings you love? Where is your magic? How can you harness it?”

Members of UnidosUS’s consulting team Penn Hill Group gave a presentation about the federal policy landscape, and fellows prepared to share the memos they had spent most of the fall and winter developing within their teams. They would present their memos before a group of local panelists familiar with their topics. The local panelists included IPC ArtSpace owner Carl Juste, a veteran photojournalist at the Miami Herald and the son of Haitian and Cuban activists who helped to found Little Haiti; Haitian Dominican community organizer Fran Menes, founder of CommUnity Strategies LLC and deputy organizing director of the nonprofit good governance group Local Progress; UnidosUS’s own Florida Policy Analyst Raisa Sequeira, who identifies as Palestinian-Nica.

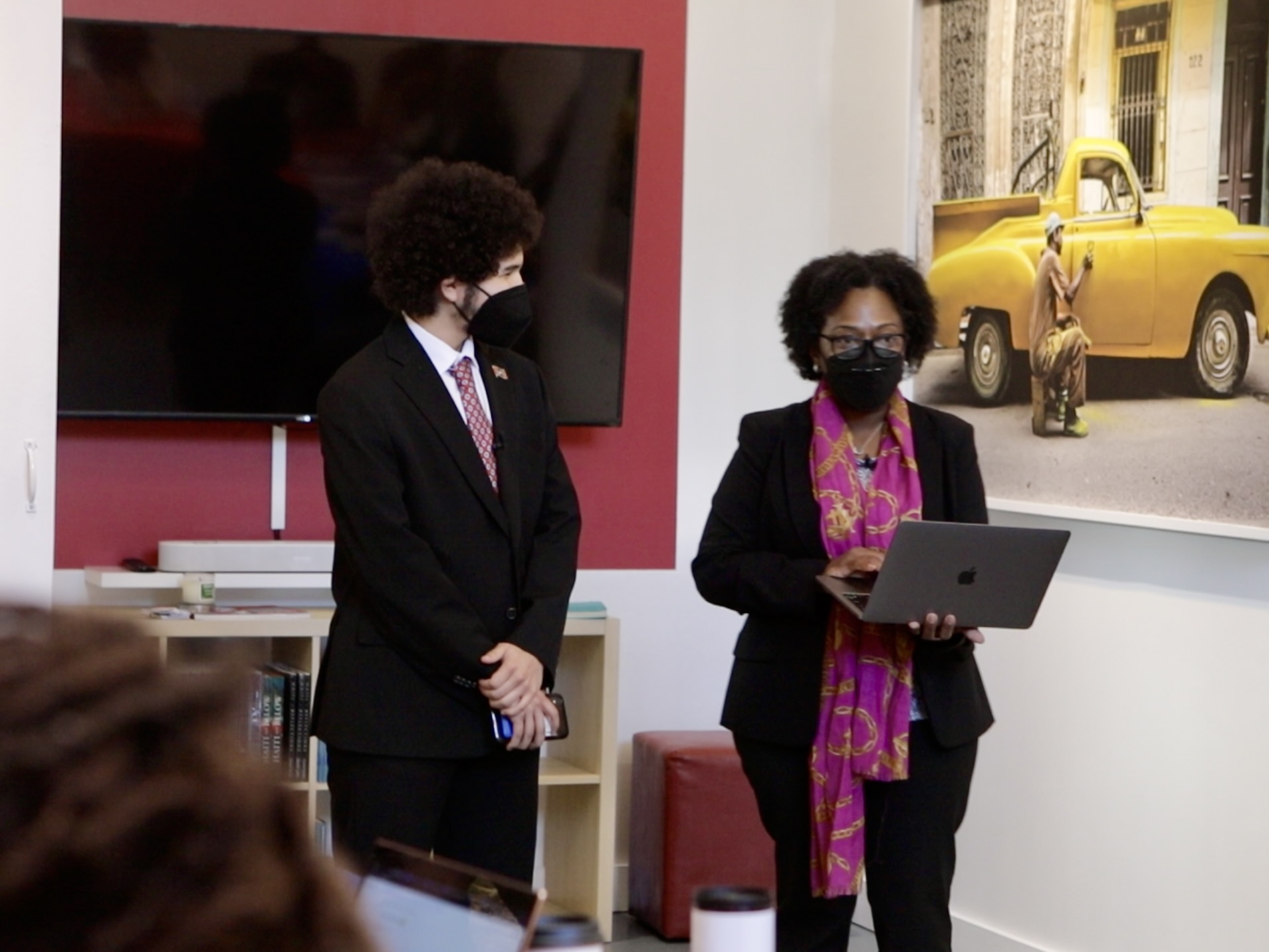

Dressed in suits and face masks and holding their research notes, the Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando teams took turns presenting their memos about access to mental health, teacher diversity, and free community college to their peers and the panel of experts.

Access to Mental Health

Orestes Marquetti, co-founder at Invest Local in Las Vegas; Dr. Dolly Martinez, a recent medical school graduate and care coordinator at the Sanitas Medical Center in Essex County, New Jersey; and Keyla Michelle Ruiz, a recent graduate of George Washington University who majored in psychology and criminal justice, made their case for the Health Equity and Accountability Act of 2020. This legislation is aimed at addressing health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities, women, the LGBTQ+ community, rural populations, and other socioeconomically disadvantaged communities across the United States

“In the United States, 18% of the population identifies as Latinx. Of that 18%, over 16% identify as having a mental illness. The Latinx community is deprived of mental health resources,” noted Ruiz. She and her team cited language barriers, cultural mores, lack of funds, and out-of-date demographic information as contributors to the problem.

“How do we allocate resources to communities if we don’t have this data?” asked Martinez. She noted that there is no data specific to Afro-Latinx for this type of work. This means researchers must infer based on separate data sets for Black and Latinx communities. “We here, my colleagues and I, live at that intersection between both identities.”

Marquetti said these concerns are what propelled him to obtain a bachelor’s degree in multidisciplinary studies with concentrations in communications and finance. “The numbers tell stories,” said Marquetti, noting that 78% of Latinx who seek advice on their mental well-being go to a family member, a church leader, or someone other than a fully trained mental health professional for a number of reasons, including because they lack the resources, there aren’t enough mental health providers available, or because seeking such services was stigmatized.

“I see this when I speak with someone like my own father, where I can just see that he doesn’t have the language to be able to communicate what’s going on in his emotional world,” said Marquetti, who noted that in his native Cuba, his father was trained to look tough and be macho.

This presentation was followed by two teams who advocated for Bill S.2125, the Counseling Not Criminalization in Schools Act, which seeks to stop the school-to-prison pipeline.

The first team to present included Nodia C. Mena, a University of North Carolina doctoral student in education leadership and cultural foundations, and Jorge “Andy” Flores, a third-year student of public policy leadership and philosophy at the University of Mississippi.

Mena talked about how racial and ethnic biases contributed to her own children being unfairly treated as disciplinary problems in North Carolina.

“I know first-hand the multiple layers of traumas that are generated in students after being exposed to disciplinary policies in school,” Mena told panelists. “My child would explain to me that his laugh was perceived as loud and that him asking to go to the bathroom would be perceived as suspicious.”

“Who’s going to deescalate a situation whenever a kid is deemed aggressive when they’re actually just in pain?” asked Flores. “We’re talking about social workers, we’re talking about counselors, we’re talking about psychologists and nurses.”

These concerns were echoed by a trio of three Afro-Panamanian fellows comprised of Raveneau, who now serves as the vice president of the Latina-run group Spitfire Communications; Emily Gardin Ríos, a development coordinator and associate consultant for the Atlanta-based social outreach consulting firm Purpose Possible; and Josefina M. Ewins, a political science and philosophy major at Rutgers University.

Ewins said that her sister teaches in a low-income junior high in Philadelphia, and that she has a 14-year-old student named Jayme who lives these social and emotional challenges every day. Jayme wakes up early to feed, dress, and walk his younger siblings to school before taking public transportation to his own classes. He often shows up tired, hungry, and irritable from the daily routine, one that doesn’t give him much time to feed himself.

“Instead of being able to process these things with a counselor who understands how to guide you through these things, you’re doing it all on your own, you’re going through puberty, you’re thinking everything’s against you because no one quite understands why you have to go through this,” Ewins told the panelists.

“Children like Jayme are experiencing this economic predicament that we as adults have put them in. It’s not just what’s happening with his parents, but what’s happening with society that has made this situation his reality,” added Raveneau.

“Even though we do want to focus on counselors in general, we need these counselors to be socially and culturally competent,” said Gardin. “Children are one of the most vulnerable populations, but they are also the future leaders of our nation, so we need to think about them in a way that’s actually constructive to their betterment and advancement, and not just their overall survival.”

Recruiting and Retaining Diverse K-12 Teachers

Julianna Collado and Zimar Batista noted that greater support for attracting and retaining a diverse teacher workforce could also contribute to the mentorship and sense of belonging that students need to move through their K-12 education and on toward college. They advocated for the Strong Act of 2021 which would expand financial support for teacher preparation and certification programs, including funding for teacher residencies, loan forgiveness and repayment, service scholarships, and relocation incentives for teacher candidates.

Collado observed that even though 50% of U.S. students are children of color, 80% of teachers are white and 40% of students don’t have a single teacher of color. She recalled her own experience as one of six Black people in Maineville, Ohio (including her four siblings and her Afro-Cuban father), where she only had one Black and one Latinx K-12 teacher, leading her to feel isolated and more vulnerable to microaggressions.

“To catch up to the current demographics, we would need a million more teachers of color,” she noted.

Batista said that he started his professional career as one of those desperately needed teachers of color in the District of Columbia Public Schools, which is 68% Black and 18% Latino, but he didn’t have access to the types of support this legislation aims to provide.

“Due to the lack of guidance and not having proper resources for teachers that looked like me, I had no other choice but to transition from this career,” said Batista.

Free Community College for Low-Income Students

Another way to improve representation in teaching and other professions is to provide free community college to low-income students, noted Gary Enrique Bradley-Lopez, a Grand Canyon University doctoral student in education and organizational leadership and development, and Aisaiah Levon Pellecer, a philosophy and economics major at Bard College. They said college enrollment among students of color had drastically dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the federal government should take that into account when balancing its greater budget for pandemic recovery.

“We want this free tuition to community colleges for low-income students to work in tandem with these infrastructure investments,” Pellecer explained, calling these institutions of higher education “an engine for social mobility.”

Bradley-Lopez said a full-ride scholarship to community college gave him the boost he needed to move quickly into a four-year degree, straight on to a master’s, and now his current doctoral program.

“Education’s always been a big thing for me, but more than that, it’s always about making sure that Black and Brown people that live like us are always up in the front and that they’re being supported by institutional change,” he told the group.

On lunch breaks and after each day of workshops and presentations, the fellows gathered among the vibrant Caribbean murals that adorn the terrace of the Little Haiti Cultural Complex to chat with each other and offer some reflections to ProgressReport.co.

UnidosUS had chosen this space for this module to help the Afro-Latinx fellows absorb and celebrate the intersectionality of their identities and that of their ancestors. That resonated with Collado, who noted that she was largely deprived of learning about Black and Latinx historical figures during her K-12 experience.

“Being able to have those conversations and dissect our experiences, our feelings, and our priorities makes it so that when we leave this place we’re able to talk about them from a place of authority, from our lived experience, and also from being in community,” said Collado.

TRAINING MODULE III: Policymaking in Practice

During the final module in April, participants were able to channel all the bonding, reflection, and preparation they built in Miami into an action-packed visit to Washington, DC, where they presented their memos to members of Congress. The four-day program began with another federal landscape analysis, updating them on recent policy changes and new priorities in Congress. They also joined a workshop called Envision the Future We Want, which encouraged them to look at the concept of Blackness and the experiences of Black people. From there, they jumped into virtual and online Congressional visits, meeting with two to four Congresspeople and their staff each day.

“It was really affirming and inspiring to continue the work that we are doing as a collective, opening the spaces and lifting the voices of marginalized communities,” Ewins said.

Toward the end of the program, fellows met with Afro-Latinx education policy leaders Sabrina Terry and Rebeca Shackleford, both former UnidosUS staffers who provided the organization with research on the Afro-Latinx community and helped to build the idea for the Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship program.

“Meeting the two women who put this idea of a fellowship together just showed how years of work and planning come before the actual developed program,” Ewins added. “It was nice to honor them.”

The final stages of the program wrapped up much the way they started, with inspirational talks from their leaders, sharing sessions on how to take this training forward, and conversations on how they might do so together. During a final graduation ceremony in Washington, each participant received a certificate and a stole before hearing words from graduating fellow Bradley-Lopez, whom they had chosen to give the program’s final speech.

He started with the struggles he had been having nine months earlier when he signed on to the first fellowship Zoom meeting. He had recently quit a community organizing job that was giving him strong leadership skills but burning him out during his studies.

“When I entered that zoom room, saw some of y’all faces, and continued to see more of you, something just felt right. It was warm, it was dope, it was emotional, it was melanated, and it was new,” he told them as he reminded them of how they will go forward and be the change they’ve all been longing to see in society.

“Your faces, your accents, your vulnerabilities, the diversity, the experience and the youthfulness of some of the wisdom of others created the first-ever Afro-Latinx Líderes Avazando leadership program.”

-Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS senior web content contributor and the former editor of ProgressReport.co. She is also the producer of the feature video, which was shot and edited by UnidosUS contributor Jayme Gershen.