Black History Month 2021:

Here’s How UnidosUS is

Exploring the Intersection of

the Black and Latinx Experience

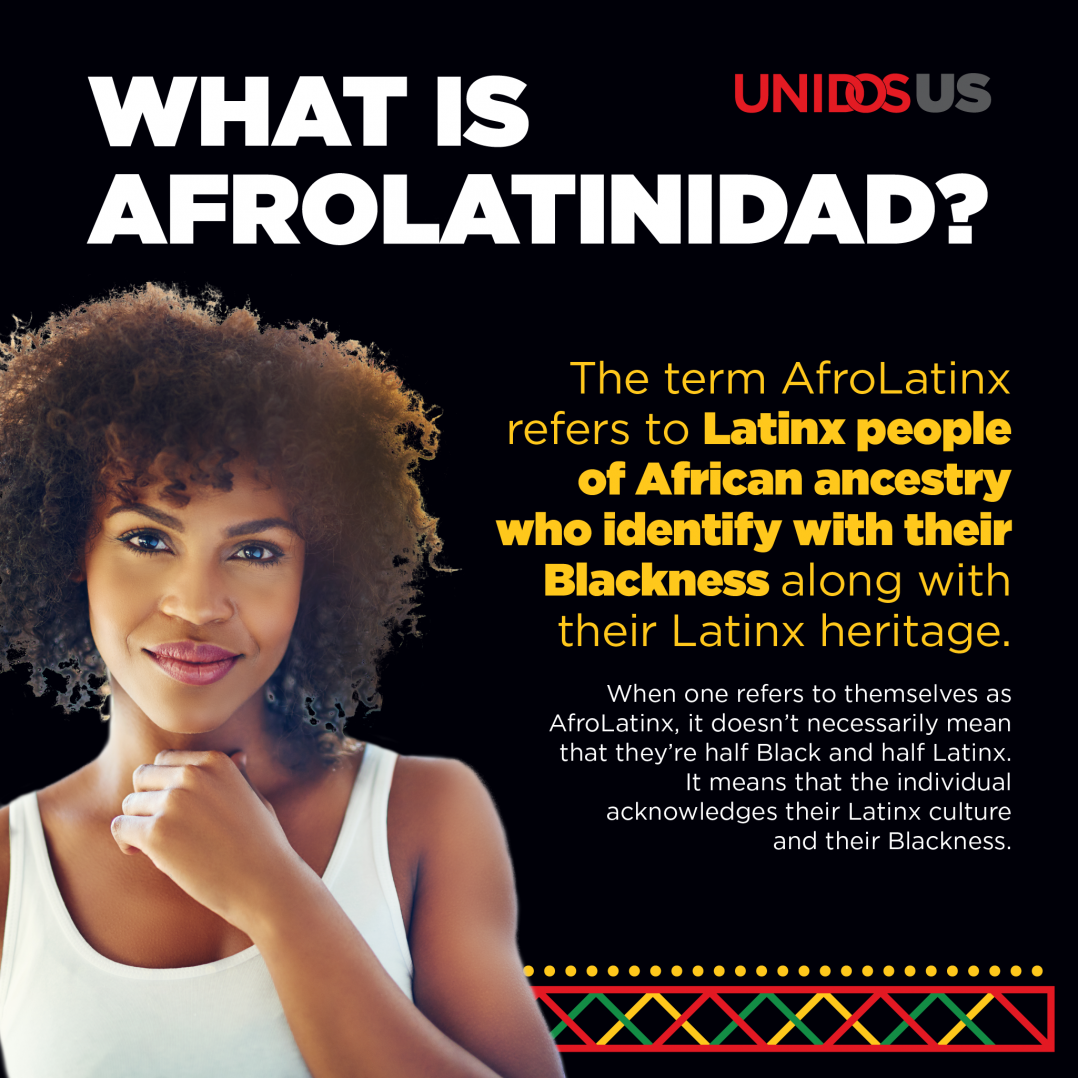

People of African descent have long made up a large part of the Latin American and U.S. Latino communities, but many people are only beginning to learn and acknowledge AfroLatinidad.

UnidosUS recognizes its responsibility to lead in this conversation within the U.S. Latino community, as part of our work to acknowledge, confront, and dismantle systemic racism. This process has recently included: a preamble about systemic racism to our major paper in June 2020 on the impact of the coronavirus on the Latino community, discussing issues of racial justice at our 2020 Annual Conference, and a soon-to-be-released primer that will promote the inclusion of Latino perspectives in public discourse racial justice and systemic racism.

In addition, in 2019, the organization released its first-ever document identifying and defining these terms and looking at just how many people identifying as Latino or Hispanic also identify as Black. Around that same time, ProgressReport.co began seeking interviews and guest blogs from educators and community advocates identifying as AfroLatino, Non-Latino Black American, and Latino Non-Black, to further that awareness. ProgressReport.co works in collaboration with UnidosUS’s education and its racial equity teams to cover this intersectionality, and this year, it’s kicking off Black History Month with a collection of prior its blog posts about AfroLatinidad. We hope these stories can continue to generate important learning and discussion about Black and Latino excellence as well as the multifaceted struggles of people of color.

In the United States, the stereotypes of who fits into what ethnic or racial category are so reinforced by pop culture and public education that many people remain unaware that people of African descent came to all corners of the Americas during enslavement. Plus, history as seen through the eyes of the oppressed has always been suppressed.

In the introduction of that book, he stated: “I wrote this book because as a scholar I want to ensure that no Latinx or Black children ever again have to be ashamed of who they are and of where they come from.”

During the summer, protests and demonstrations over the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and so many others grew and spread across the country and around the globe and sometimes met violent responses from hate groups, Oritz reaffirmed the importance of historical review.

“In order to learn how we get out of the mess we’re in, we have to learn the contemporary context for which movement organizing is taking place,” he said. He added that throughout 200 years of American history, there are obviously many ugly chapters, but in the midst of them, there are also incredible accounts of Black, Brown, and sometimes even White folk communicating, coordinating, and conspiring to overturn injustice and write new chapters. People in power actively tried to cover up the stories of the collaborative efforts that emancipated enslaved peoples in the United States, Cuba, Mexico, and Haiti, because each victory showed that change was possible.

The fruits of those struggles were a point of interest to Rosalyn Damiana Lake Montero, an AfroLatinx educator and civil rights activist participating in the DC AfroLatino Caucus in Washington who wrote about Juneteenth for ProgressReport.co. Born in the Dominican Republic and raised in the Mid-Atlantic United States in the American public school system, she noted that she hadn’t gotten much of a history lesson on the topic. Juneteenth marks June 19, 1865, the day enslaved people in Texas learned that they were finally emancipated. Even though President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation two years prior, Texas had continued to officially allow the formal practice of slavery until that day.

“It was very empowering to learn that Juneteenth, also known as Emancipation Day and Freedom Day, is now observed as a state holiday or commemoration in all but four U.S. states, and that now there’s talk of making it a federal holiday,” she wrote. “But the more I learn, the more frustrated I become that it isn’t one already. And I’m also concerned that there really aren’t any celebrations of the abolishment of slavery back in my native Dominican Republic.”

Ultimately, Lake Montero used her Juneteenth research to reflect on her own AfroLatinx experience, then invited readers of all backgrounds to research and reflect on their historical connections to slavery and the struggle for emancipation.

That same spirit of intersectionality inspired Spanish-speaking Black American, non-Latina filmmaker Kim Haas to produce an educational documentary series about AfroLatinidad across the Americas. Last fall, as the first two Costa Rica-based episodes of Afro-Latino Travels with Kim Haas began airing on PBS stations across the country, she gave an interview to ProgressReport.co to share some of the knowledge and excitement she gained in connecting with Black folk in other parts of the hemisphere and looking at Black identity as an inter-American concept. She said she most appreciated the way the arts in all countries have been used as a form of resilience and resistance among oppressed peoples. For example, she noted that popular songs have often been used to mobilize people around civil rights.

“A lot can happen around a song, Haas said. “The arts have a way of connecting people where maybe you wouldn’t be able to make that connection another way.”

She also encouraged anyone with a desire to research and share stories to feel empowered to do so. “Just because you come from a background where maybe you haven’t had as many opportunities doesn’t mean you shouldn’t share your experiences,” Haas said. “We absolutely need to hear about your experiences and see your talent, creativity, and strength. Your unique perspective needs to be shared.”

Many of the sources interviewed over the past year noted that you shouldn’t let the confines of the pandemic or the hefty price of film production stop you from engaging in the discovery process right now. Between the Internet and socially distanced museum, library, and other community outreach initiatives, there are plenty of ways to learn about Black History and AfroLatinidad wherever you happen to be based

During ProgressReport.co’s 2020 coverage of Black History Month, DC AfroLatino Caucus Founder Manuel Mendez told ProressReport.co how he grew up with a lot of Black history in Washington, DC, a city many locals affectionately call “The Chocolate City” for its historically large Black population. The more he researched, the more he came to realize Latinos of many ethnic backgrounds had been traveling through or living in Washington long a mass migration of them arrived in the area during the latter half of the 20th century. Soon, he was discovering Black leaders in DC history also happened to be Latinx, and that led him to seek out and build relationships with local AfroLatinx leaders still living in and serving the community today.

“We need to start looking at our neighbors and being like ‘you’re important, let me interview you, let me see why you’re here.’ Mendez told ProgressReport.co in an interview for last year’s Black History Month coverage. “Go out and collect those stories and experiences, talk to the elders.”

In fact, thanks to efforts of Mendez, ProgressReport.co was able to connect with and commission the aforementioned Junteenth blog from Lake Montero.

Discovering those local stories can do wonders for building social awareness and community and personal pride. It can also encourage more frank conversations in interracial settings, noted AfroLatina educators Vanity Duran and Amanda Edgerton during interviews to teach the identities of ladies like them on International AfroLatinx Women’s Day, which takes place each year on July 26.

In a world so impacted by the legacy of White supremacy, including White beauty norms, it can be incredibly awkward but also vitally important for young people to delve into discussions of how to appreciate and celebrate each individual’s natural appearance.

Going up and touching a Black person’s hair without a prior invitation is widely seen today as a sign of ignorance and disrespect. Still, Duran explained that a Black person hosting a discussion about their Black beauty, and even choosing to host a demonstration about what makes their hair or skin special and unique could be an entrée into all kinds of deep inter-racial discussions.

“Everyone’s hair gets wavy when its wet. That’s one way of showing us that we’re all one,” Duran said. “Then we can look at different types of textures and curls, and learn to embrace our beauty in our own way.”

This is just one of many ways to engage students in storytelling, added Edgerton, noting that it took a lot of sharing of her own upbringing as a the daughter of a Mexican immigrant and a Black, non-Latino American, to finally refer to herself AfroLatina or Blaxican.

“Even at almost 30, I’m still working on that,” said Edgerton, now working as a math teacher in Jacksonville, Florida. “I definitely didn’t get any help from my school about history. I had to find out stuff on my own.”

But today, she believes even a class as quantifiable or as, well, square, as geometry can turn into a space for personal storytelling if educators are willing to build those stories into the curriculum or simply leave some time for impromptu class discussions.

“I want them to leave my class with those intangibles,” she told ProgressReport.co.

Also somewhat intangible? Who decides who’s in and who’s out of what ethnic category. ProgressReport posed these questions to veteran Miami Herald photographer Carl Juste in a blog post titled Are Haitians Hispanic?

Juste spent his whole childhood and much of his career winding through that historical labyrinth. His Haitian father and Afro-Cuban mother, also of Haitian heritage, helped to found South Florida’s Little Haiti neighborhood. In the process, they worked tirelessly to educate the public on how a successful slave revolt on the island of Hispañola created Haiti, the world’s first Black republic, and used that point of pride as a way to engage other ethnic communities in the struggle for interracial solidarity. Juste built his own award-winning photojournalism on their legacy.

“The whole island of Hispañola was fought over by the British, French, and Spanish, so I think those geographical and cultural intersections should be taught,” said Juste. “I think it happens with an Afro-Latin intersect, and I consider French a Latin language, so I could be Latinx as much as anybody else, but I see it more as the intersection of common values and the connection to Africa.”

And finally, whether you’re in a diverse or relatively homogeneous setting, technology can and should be a tool for multicultural enlightenment. In 2019, ProgressReport.co worked with diverse members of the UnidosUS staff to curate this list of five ideas for teaching AfroLatinx history through a series of online resources, with the idea of pointing out historic characters and communities many folks might not have known were of both African and Latinx roots.

“It’s important to have conversations about race and not just ethnicity. Growing up, I was immersed in my Mexican and Ecuadorian roots, but I did not learn that I was an afro-descendant until my mid-twenties,” notes Education Leadership Program Manager Washington Navarrete. “Because I wouldn’t be racialized as Black by the general public, I learned about the impact of the slave trade in South America and began to notice and understand the features I saw in many of my family members on my dad’s side.”

Navarrete says this discovery process has led him to have more nuanced conversations about race and ethnicity with the students and school leaders he serves through his role with UnidosUS, and it has also had him reflecting on the ways those conversations played out while teaching first-graders with Teach for America in the Mississippi Delta.

“While these conversations look different depending on the age, we can’t shy away from having them more broadly,” he added.

Over the past several years, UnidosUS has been working with its AfroLatinx and afro-descendent familia to “strengthen an understanding of AfroLatinidad history, contributions, needs and challenges,” through a much bigger curriculum which is scheduled to launch during Latinx/Hispanic Heritage Month next September, says UnidosUS Principal of Education Programs Feliza Ortiz-Licon.

“The racial diversity within the Latinx community has often been limited by fixed categories of Blackness and Latinidad; therefore, AfroLatinos have been ignored and/or overlooked in the Latinx community,” she says.