Afro-Latinx Líderes Fellow Dolly Martinez Shares How the Program is Helping Her Explore Her Identity and Become a Leader

For this year’s Black History Month coverage, ProgressReport.co is kicking off a profile series about the participants of UnidosUS’s first-ever Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship. The program is geared to first-generation students pursuing their undergraduate, graduate, or doctoral degrees and recent college graduates who identify as Afro-Latinx and are passionate about racial equity and making meaningful change in their campus community, workplace, and beyond. Publication of the Afro-Latinx Líderes profiles will continue throughout the spring.

In 2013, a then 21-year-old Dolly Martinez left her childhood home in New Jersey to learn more about her Afro-Latinx roots in the Dominican Republic.

“In school in New Jersey, people didn’t know what I was, and I didn’t know how to explain it—like why I look the way I look and how I speak Spanish,” says Martínez, who says her goal was to do a bit of “soul searching.”

“In school in New Jersey, people didn’t know what I was, and I didn’t know how to explain it—like why I look the way I look and how I speak Spanish,” says Martínez, who says her goal was to do a bit of “soul searching.”

She did that and so much more. Six years later, she came back to the Garden State with a medical degree obtained in a place that helped her gain a better sense of the place and role she wants to have in a world of so many social and economic contrasts. Today, she’s one of 12 young professionals participating in the UnidosUS Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando policy and advocacy fellowship, an opportunity that coincides with her preparation for medical residency.

She did that and so much more. Six years later, she came back to the Garden State with a medical degree obtained in a place that helped her gain a better sense of the place and role she wants to have in a world of so many social and economic contrasts. Today, she’s one of 12 young professionals participating in the UnidosUS Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando policy and advocacy fellowship, an opportunity that coincides with her preparation for medical residency.

“I felt that, for the first time, there was something out there created specifically for me. I knew UnidosUS didn’t know who Dolly Martinez was, but the Afro-Latinx Líderes fellowship checked all the boxes—Afro-Latina professional, first generation in the United States. I knew it was speaking to me,” says Martínez, who discovered the program through her participation in the personal and career growth cohort called Elevink.

The Afro-Latinx Líderes fellowship is helping her build her network and hone her leadership skills as she considers how to serve communities across the country as a doctor. At the same time, the experiences she forged in her parents’ home country allow her to give the Líderes program as much insight as she gains. After all, many of the fellows are trying to figure out the fragmented pieces of their own cultural, ethnic, racial, and linguistic heritage. And given her experiences in the Dominican Republic, she knows it’s a process.

For example, she arrived in the town of San Pedro de Macorís to find lot of Spanish speakers who looked just like her. They lived their African heritage as she had always done at home—through food and music. And yet, they didn’t really talk about the history or the impact of the slave trade.

“People don’t talk about the importance of Blackness in the Dominican Republic,” she lamented, at least not in everyday conversation. As such, she spent much of her time simply living the experience and observing. She participated in Dominican Folklore Dance and visited the different towns that hosted the patronal festivals, appreciating and exploring her identity through music and art. When she wanted to go deeper into why this was, she would occasionally consult her uncle who is on his own self-discovery journey.

Then came medical school, which exposed her to all kinds of social and economic scenarios. For starters, she realized the conversational Spanish she had spoken with her family had not prepared her for the academic jargon she’d find in class and textbooks. Plus, she’d never lived in a place where the dwellings and workplaces of the rich and poor were comingled.

“We took a community-based health class where we would visit people’s homes. You might enter one home that looks just like a home here – four walls, a floor, windows, a roof—and you might enter another made of old, warped, recycled pieces of scrap wood with tin roofs and a dirt floor,” says Martínez.

She says the experience helped her to feel grateful for the things she has, making it easier to decide what’s really important in the grand scheme of life.

On those site visits, medical students were taught not just to observe the conditions but help empower residents make small improvements that could lead to better health outcomes. For example, many homes had no internal plumbing, just tanks to store water—water that might be used for bathing, cooking, and drinking. As such, students would help residents wipe down their tanks, sinks, or bathroom facilities with disinfectants and put water purifying packets into the water tanks. These simple steps could go a long way in preventing the spread of water-born illnesses and infectious diseases.

The visits also helped her gain a stronger sense of empathy with patients—ones she saw as a student there, and as a soon-to-be doctor-in-resident in New Jersey.

“Now that I’m back here, I don’t think about empathizing because it’s ingrained in me. It’s easier to give better care,” says Martínez.

While most water systems in the United States are filtered or chlorinated, contaminated water is still a health risk in the United States, and lack of access to healthy food, warm, safe housing, and affordable health care can certainly pose a risk to everything from COVID-19 to hypertension and diabetes, Martínez notes.

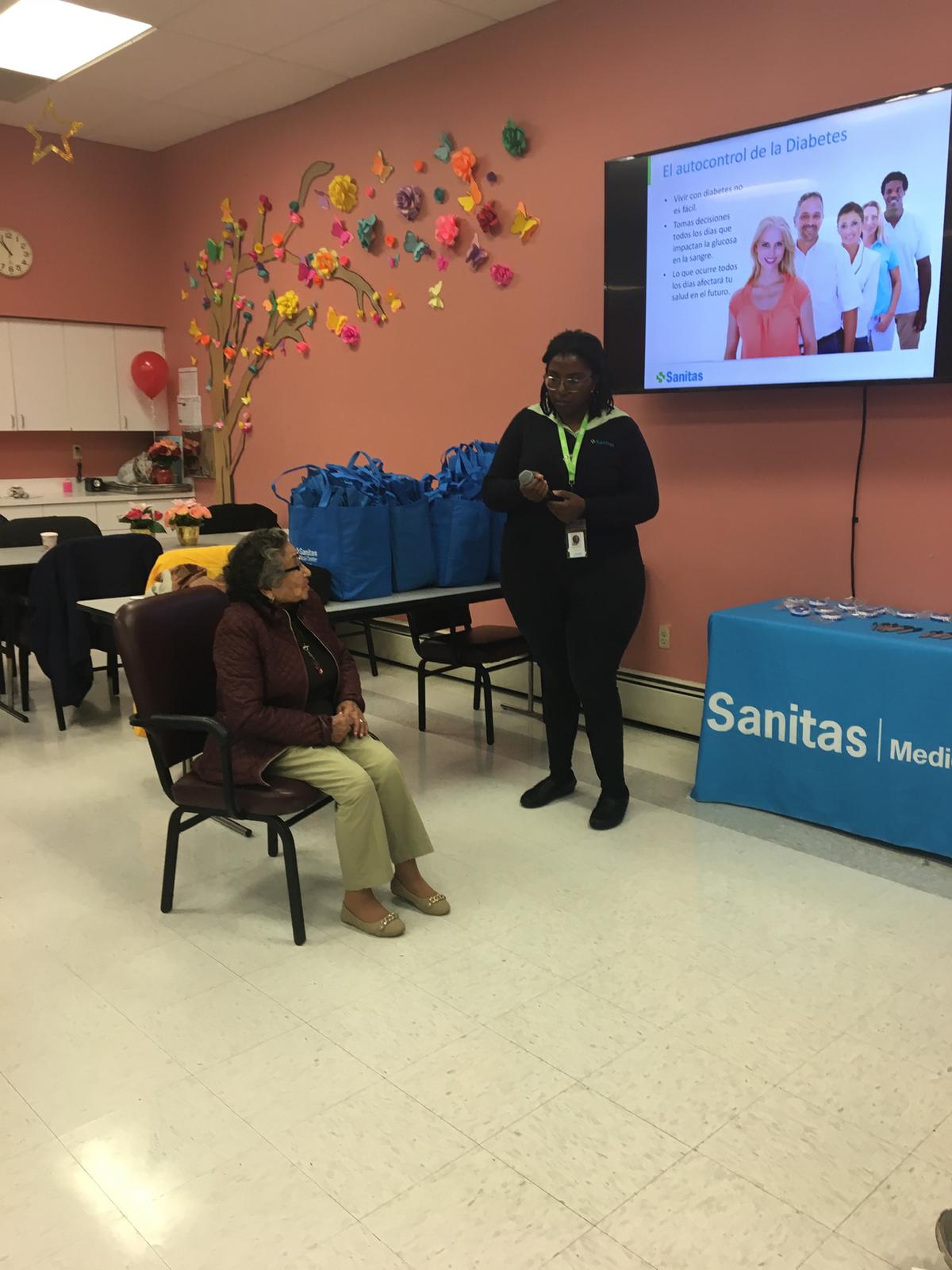

This impacts her work as a care coordinator at the Sanitas Medical Center in Essex County New Jersey. They have so many diabetes patients with dangerously high hemoglobin levels that she’s helped to organize and lead a six-month healthy food program that helps these patients make affordable, healthy changes to their diet by doing things like reading the labels on pre-packaged foods.

“Health and quality of life is affected by socioeconomic status, education, and social support. Unfortunately, low-income communities have a large disadvantage in accessing adequate health care due to these social determinants,” she says.

But even as she awaits her medical exams to start her residency, she knows she can be instrumental in disseminating information on how to access health care.

“I just try and walk them through the process” she says. ”I recently met with a patient and I let her know the process for applying for disability because she’s paying out of pocket for insurance and she’s not working. I can’t apply for her, but now at least she knows these things exist.”

Harnessing the Afro-Latinx Líderes Fellowship

Martínez says the Afro-Latinx Líderes fellowship is helping her to identify opportunities for growth in her personal and professional life, while helping grow public awareness of what it means to be just who she is—a Black Latina professional with her feet in more than one country and culture.

“I think that the best part in being in the Líderes program so far is honestly seeing more faces like mine. I did notice that I’m one of the only fellows in health care, but because everyone there is climbing the ladder, there’s so much potential,” she says.

Getting to know Afro-Latinx professionals operating in all kinds of career fields furthers her understanding of who’s out there and what’s possible.

“I wasn’t exposed to that at all. When I’d think about Afro Latinos, I’d think about people in the media—musicians, actors, but not in other professional careers,” she explains.

And those soul-searching questions she went looking for back in the Dominican Republic? She says she’s learning it’s okay to have some still unanswered.

“It’s having the space to have these uncomfortable conversations. It’s okay to be prepared for not having all your questions answered. It feels like a safe, judgement-free zone,” Martínez says, adding that there’s no pressure to “pick and choose” one aspect of your identity over another.

“I’d been away for a long time, and I was looking do networking, to meet people who are either on the same path or know of the path and can help steer me in the right direction,” she says.

-Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS Senior Web Content Manager and the editor of ProgressReport.co.