Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellow Orestes Marquetti Explains His Passion for De-stigmatizing Mental Health

For this year’s Black History Month coverage, ProgressReport.co is kicking off a profile series about the participants of UnidosUS’s first-ever Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship. The program is geared to first-generation students pursuing their undergraduate, graduate, or doctoral degrees and recent college graduates who identify as Afro-Latinx and are passionate about racial equity and making meaningful change in their campus community, workplace, and beyond. Publication of the Afro-Latinx Líderes profiles will continue throughout the spring.

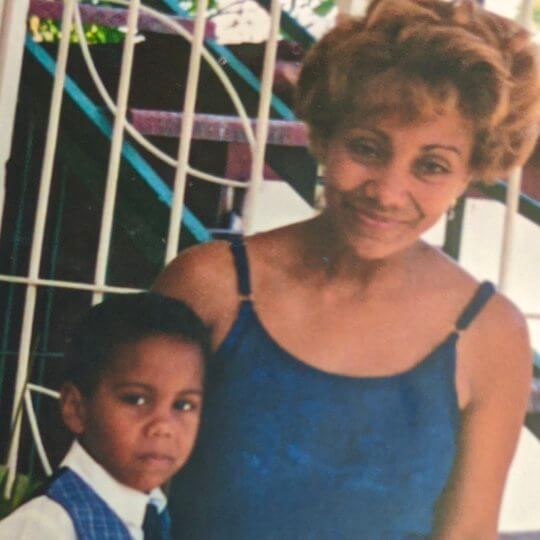

As a child growing up in Havana, Orestes Marquetti always suspected he was destined to do something of great value in the United States, and he certainly knew he was going to get to this country come Hell or high water.

“I was prepared to come to the United States my entire life,” says Marquetti. “My parents were always telling me ‘hey, you don’t belong here. We’re gonna get you over there.’”

His birth in 1996 came just two years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and since that Cold War empire was the primary funder of Cuba’s socialist revolution, the Cuban economy went down with it. Social and political conflict on the island soon followed, prompting many Cubans to flee the country in search of greater social, political, and economic self-determination.

Marquetti’s parents tried numerous times to defect through third countries such as Trinidad, Venezuela, and Belize, exploring different avenues for long-term residency in them as they make a legal case for entering the United States. Finally, in 2004, after a month traversing Mexico, they walked up to U.S. border agents in Brownsville, Texas, and declared that they were Cubans seeking asylum. Because of the contentious Cold War relationship between the U.S. and Cuban governments, U.S. policy has historically provided more migratory leeway to Cubans than to other nationalities in this hemisphere. The U.S. agents allowed them to walk straight through. A few days later, a then-eight-year-old Marquetti and his family boarded a Florida-bound bus to a new life.

Growing Up Afro-Latinx in America

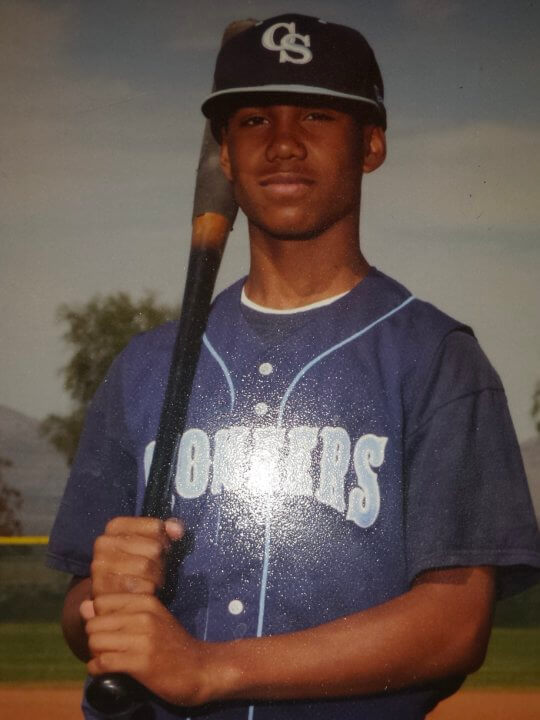

After two years living in a predominately Black American community in Tampa Bay, the family decided to relocate to Las Vegas for better job opportunities. That’s where Marquetti would finish high school and ultimately graduate last winter with a major in multidisciplinary studies with finance and communication studies concentrations from University of Nevada, Las Vegas, alongside his wife and classmate Vivianna Marquetti. Having emigrated so young, he quickly learned English and lost his Cuban accent, but he never quite knew in any community where he belonged. Most Americans, including other Latinos, simply saw him as Black.

“That always comes up for me here in Las Vegas because there aren’t very many Latinos from places like the Dominican Republic, Cuba, or Puerto Rico,” says Marquetti, naming some of the places in the Americas with large Afro-Latinx populations.

That reality, and his insatiable curiosity for understanding the motivations of all people, recently led Marquetti to apply for master’s programs in organizational communication and to join the Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship. He’s using his fellowship to consider how his graduate studies can lead him into a career as a corporate social responsibility consultant, working directly for companies interested in this activity or holding companies without such a vision responsible for the way their business impacts everything from the environment to the most vulnerable people in it.

“I’m interested in the intersection of finance and communications because it gets into how people exchange messages and meanings, and how they create values,” he says.

Harnessing the Afro-Latinx Líderes Fellowship

The Afro-Latinx Líderes Fellowship requires participants to break into a team of two to three people and spend the nine-month program working together on a policy and advocacy issue affecting the Latino community. Given Marquetti’s interests, he chose to join the team looking at mental health.

“I believe that businesses have the most power for change, but how can individuals be productive members of society if they’re struggling with mental health and not getting the care that they need?” Marquetti asks.

His team is looking at how to destigmatize mental health issues in the Latino community and improve access to psychological services, all of which can help them become more integrated and prosperous in their personal and vocational lives.

Business, communications, care of the soul. These are all things Marquetti comes by naturally. Back in Cuba, his father traded a low-paid state job as an engineer for a more esoteric and ancestral one as a Babalao, a high priest in the Santería religion which is rooted in Africa’s Yoruba spirituality. His mother, who worked in Havana as a housekeeper and nanny for a Spanish ex-pat family, also became a Santería services provider.

It’s a belief system that has long existed among people of African descent throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. For example, in Brazil it manifests itself as Candomblé, and in Haiti as Vodou. In spite of the bloody nature of the Bible, Western media has often portrayed it as more macabre than that of Judeo-Christian traditions, often calling it “dark” or terming it “Black Magic,” which reinforces negative stereotypes around Blackness.

All of those imposing lenses have contributed to Marquetti’s feelings of alienation, even from the Latino community. As such, the Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellowship is a perfect space to talk through these frustrations of identity, culture, values, and vocation.

“It’s giving me the opportunity to find that in myself, and then be able to bring it into the world with pride. I can bring that unique perspective precisely because I’m very close to my African heritage and my family’s religion,” he says. “I believe in changing people’s hearts. Immersing myself in public policy is helping me to understand how to do that better,” he said.

But even in Marquetti’s own family, that awareness of their African heritage hasn’t always translated to a synergetic understanding of what it means to be Black in the Americas. For Marquetti’s father, the Cuban Revolution, a decades long system based on Marxist beliefs of egalitarianism, didn’t offer enough sense of individual freedom. He has always felt that the United States is a place of endless possibilities. But Marquetti frequently reminds him that being Black in America comes with a constant anxiety about racial discrimination and hate. Through his studies and through the fellowship, he tells his father about the statistical discrepancies Black and brown communities face in everything from public safety to job opportunities and housing, even five decades after the advances of the Civil Rights Movement.

Recent news from the island has helped generate some important conversations about the concept of freedom and liberty in any country. Last summer, Cuba saw masses of protests organized largely by Black Cuban artists who felt the revolution had not lived up to his egalitarian promises. Like Marquetti’s father, they want greater civic engagement and control of their own financial destinies.

“He wants me to be aware of this and understand it, so I keep up to the extent that I can,” says Marquetti, who has returned to the island several times throughout his life. “But I try and help him understand how what’s relevant to me is walking around my college campus or my community and being perceived as a threat because I am a tall, Black man.”

For many Latinos, grappling with these with different generational and ideological perspectives can be worked through and even harnessed by what has become popularly known in Mesoamerican and Chicano activism circles as la cultura cura. It’s the idea that exploring the cultural traditions and spiritual practices of one’s ancestors can help to heal some of the trauma associated with colonialism and racism, as well as empower individuals and communities to push for greater participation and acceptance in today’s world. It’s a concept Marquetti and his Afro-Latinx peers are leading through their own exploration of Black consciousness.

“It’s really taken a lot of work to try to uncover the layers to this subject, but it’s really been worthwhile to dig deep,” says Marquetti.

-Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS Senior Web Content Manager and the editor of ProgressReport.co.