Potential Medicaid loss threatens health care for millions of Latinos

A new federal report finds that 4.6 million Latinos* and 5.5 million children are likely to lose Medicaid when the COVID-19 public health emergency ends, if pre-pandemic policies and practices do not change. These Medicaid losses will be by far the largest in American history.

In some ways most shocking, nearly two-thirds of the Latinos losing coverage and almost three-fourths of the children will remain eligible for the program but be terminated because of red tape and missing paperwork. By contrast, such administrative factors are projected to end coverage for just 17% of non-Hispanic Whites who lose Medicaid.

These new findings are remarkably similar to those from a report that UnidosUS, Families USA, and First Focus on Children released earlier this summer. That report warned of a “Medicaid tsunami” that, when it hits at some point in the coming months, threatens to cause devastating harm to the Hispanic community and other historically disadvantaged groups.

What is the Medicaid tsunami?

In March 2020, Congress passed COVID-19 relief legislation that gave states a substantial increase in federal Medicaid funding. In exchange, states were forbidden to terminate Medicaid for anyone who hadn’t died, moved out of state, or asked for their coverage to end. Both the increased federal funding and the “continuous coverage” requirement last until the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Xavier Becerra, declares that the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) is over.

Since the continuous coverage requirement took effect, Medicaid enrollment has grown by 28%, rising from 64 million people in February 2020 to 82 million in May 2022. Medicaid now serves more people than at any previous point in history. Once the PHE ends, state and local Medicaid agencies, many of which are severely understaffed, must determine whether each of these 82 million people remains eligible. Almost certainly, unprecedented coverage losses will result. We do not know when this Medicaid tsunami will hit, but it is headed our way, and it threatens to be enormous.

Latinos, children, and other disadvantaged populations will experience the largest Medicaid losses in history, if past patterns apply when the PHE ends

On August 19, HHS’s Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) released a report estimating what will happen once Medicaid terminations resume. Under a mid-range scenario with Medicaid losses at typical pre-pandemic levels, ASPE found that 15 million people will lose Medicaid, of whom 6.8 million, or 45%, will remain eligible but be terminated for administrative reasons. Based on past experience, such administrative terminations will result when states mail beneficiaries notices asking for information and do not receive a response, either because the notices were sent to the wrong address, the mail wasn’t opened in time, the notice wasn’t understood, the family couldn’t cope with the administrative burden required for a timely and complete response, the state misplaced the family’s response, etc.

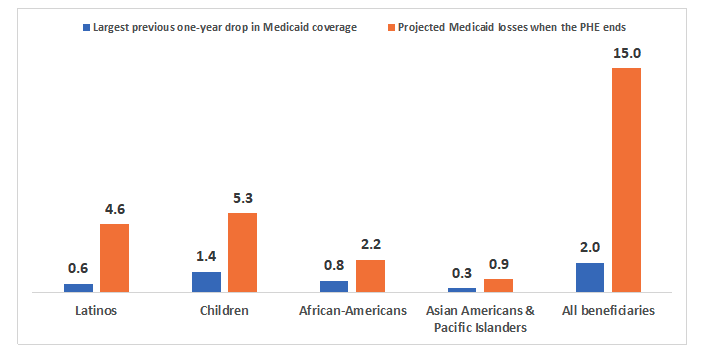

Out of 15 million beneficiaries whom APSE estimates will lose Medicaid if pre-pandemic patterns apply, more than half are people of color. Medicaid terminations are projected to include:

- 5.3 million children

- 4.6 million Latinos

- 2.2 million African Americans

- Nearly a million Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders

- Roughly 800,000 other people of color.

Each of these Medicaid losses will be the largest in history, by a considerable margin. They will greatly exceed the largest one-year drop in Medicaid coverage reported in Census Bureau data, going back to 1979. For example, the 4.6 million Latinos who are expected to lose Medicaid will outnumber, by more than a 7 to 1 ratio, the 0.6 million Latinos who lost Medicaid in 2019, the largest previous one-year drop in Hispanic Medicaid enrollment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Projected Medicaid losses when the PHE ends, compared to the largest previous one-year drops in Medicaid enrollment recorded in Census Bureau data, by age, race, and ethnicity (millions)

Sources: ASPE 2022; Dorn 2022. Note: Estimates of one-year Medicaid coverage losses are based on data from the March Current Population Survey for 1979 through 2000. The largest previous one-year drops recorded in CPS data took place in 1997 for African Americans, the year after welfare reform legislation was enacted; in 2019 for all other specific groups listed in the chart; and in both 2018 and 2019 for Medicaid beneficiaries overall. All races are limited to non-Hispanics except for Latinos, who include Hispanics of all races. Projected Medicaid losses are under a mid-range scenario, where such losses are comparable to those under pre-pandemic conditions.

Children, Latinos, other people of color, and families with very low income are disproportionately likely to lose Medicaid for administrative reasons—even though they remain eligible

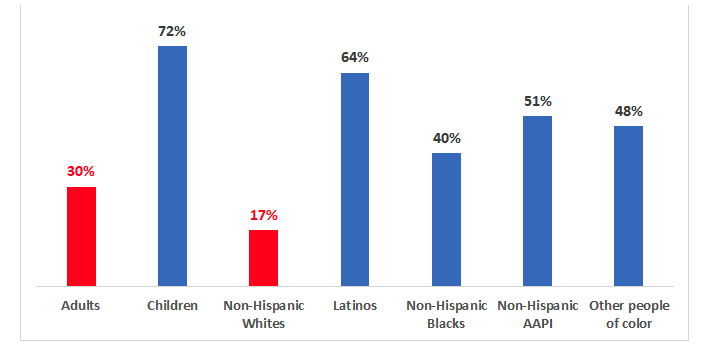

Red tape will take a particularly heavy toll on children, Latinos, and other people of color (Figure 2):

- 72% of all children losing Medicaid are projected to remain eligible but be terminated for administrative reasons, compared to 30% of adults.

- 64% of Latinos, 51% of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, 40% of African Americans, and 48% of other people of color losing Medicaid are projected to be eligible but terminated because of red tape and missing paperwork. By contrast, only 17% of non-Hispanic Whites terminated from Medicaid are expected to lose that coverage for administrative reasons.

Figure 2: Percentage of people projected to lose Medicaid who will be terminated for administrative reasons, despite remaining eligible, by age, race, and ethnicity

Source: ASPE 2022. Note: AAPI=Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. All races are limited to non-Hispanics except for Latinos, who include Hispanics of all races. Children are under age 18. The percentage for adults shows a weighted average of all groups age 18 and older. Figure shows results under a mid-range scenario, where Medicaid losses are comparable to those under pre-pandemic conditions.

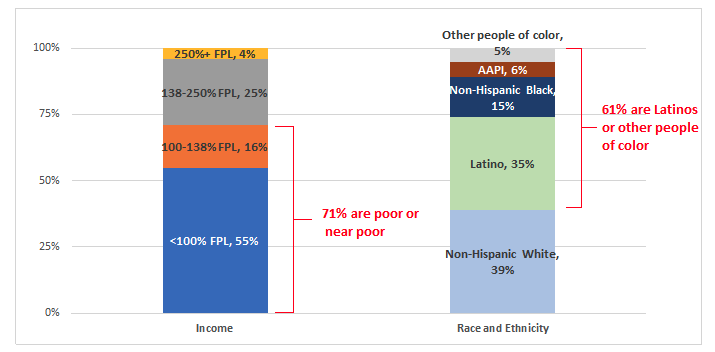

The overwhelming majority of Medicaid beneficiaries projected to lose coverage because of red tape have very little income. More than 70% are poor or near poor, with incomes below the poverty line or just slightly above it (Figure 3).

These procedural terminations will heighten racial and ethnic inequities. More than 60% of those expected to lose coverage due to red tape and state paperwork demands are people of color, including more than a third who are Latino (Figure 3).

Figure 3. When the PHE ends, beneficiaries who are likely to lose Medicaid for administrative reasons despite remaining eligible, by income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL), race, and ethnicity

Source: ASPE 2022. Note: AAPI=Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. All races are limited to non-Hispanics except for Latinos, who include Hispanics of all races. Figure shows results under a mid-range scenario, where Medicaid losses are comparable to those under pre-pandemic conditions.

Federal and state policymakers must act

As we explain in our recent report, many if not most Medicaid beneficiaries can have their eligibility determined based on data matches with reliable sources of information. Under federal law, if such data show continued eligibility, families should not be terminated based on failure to provide paperwork unless other specific information shows a change in circumstances that may affect eligibility.

To shrink the tsunami’s size and prevent eligible families from losing health care, two steps are essential:

- All states need to raise electronic renewals to the level of their highest-performing peers. Before the pandemic, Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Idaho, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, and Rhode Island all used electronic data matches for 75% or more of all Medicaid renewals. By contrast, between 10 and 15 states used data matches for less than 25% of families undergoing renewal.

- As outlined in our recent report as well as recommendations from more than 110 consumer groups, insurers, health care providers, and equity organizations, federal officials must act boldly to protect eligible families’ coverage. That includes authorizing electronic renewals based on available data whenever possible and holding states accountable to use such data to maximize renewals of eligible beneficiaries’ coverage.

It’s time to update renewal practices

Under both Republican and Democratic presidents, health programs this century have leveraged an increasingly robust national information technology infrastructure to renew eligibility automatically and maintain people’s coverage. For example, eligibility for low-income subsidies of Medicare Part D drug coverage—implemented under President George W. Bush—is automatically renewed whenever data matches show that a beneficiary received Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income the previous year. Similarly, health insurance marketplaces automatically update families’ eligibility for advance premium tax credits (APTCs) every year, based on the most recent available federal income tax returns, unless the family updates its own profile.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to realize this same vision for Medicaid. It made clear that “to the maximum extent practicable” eligibility should be renewed based on “data matching arrangements.” As with Medicare Part D and APTCs, the burden of establishing continuing eligibility was placed on the government agency, not the struggling family. Medicaid programs were required to assiduously check all “reliable, third party [sic] data,” including tax records, quarterly wage records, and the files of other need-based programs.

And under the ACA’s implementing regulations, whenever data matches verify eligibility, Medicaid should send the family a notice explaining the state’s determination and the family’s obligation to correct any errors. Renewal rather than termination is required if the state does not hear back. Only if available data does not demonstrate continued eligibility can a state Medicaid program eliminate someone’s health care just because the family did not provide requested paperwork.

If nature is allowed to take its course, America will soon experience far and away the largest Medicaid losses in history, with children and communities of color suffering disproportionate harm. For Latinos and for children, the vast majority of Medicaid terminations will result from red tape that denies health care to eligible families.

To limit the damage, it is imperative for both state and federal officials to do everything in their power to leverage modern information technology and proactively renew as many eligible families as possible based on available data. In the third decade of the 21st century, there is no excuse to terminate Medicaid because an eligible family does not provide paperwork telling the state what it is fully capable of learning on its own.

_______________________________

* The terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” are used interchangeably by the U.S. Census Bureau and throughout this document to refer to persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central and South American, Dominican, Spanish, and other Hispanic descent; they may be of any race.