The racist history of voter suppression laws

According to the Brennan Center, half of the states with the highest Latino population growth passed voter suppression laws in 2016. Five years later, Texas has become the latest state to sign into law extensive restrictions that limit how and when voters can cast their ballot.

By Julissa Arce, Activist, Writer, and Producer

Signed by Republican Governor Greg Abbott last week, SB1 bans 24-hour voting, eliminates drive-through voting, establishes new vote-by-mail ID mandates, makes it a felony for public officials to broadly send mail-in ballots, gives partisan poll-watchers more power, increases requirements to assist people with disabilities, and requires the Texas secretary of state to conduct monthly voter roll checks. Those provisions specifically target Latino communities, like Harris County, where we make up 41% of the population. This law begs the question: Why don’t elected officials, who rely on Latino votes, want to make voting more inclusive and accessible for their own voters?

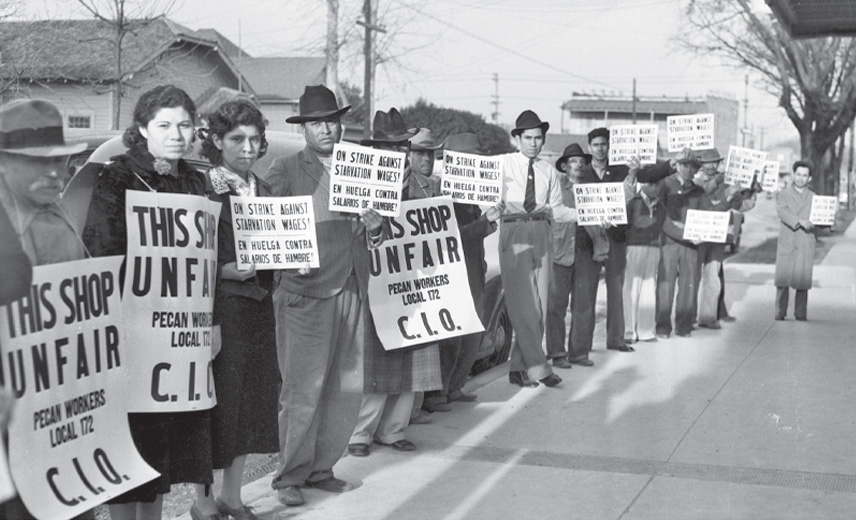

These voter suppression tactics continue a long legacy of efforts to silence us at the polls. Let’s expose the structurally racist roots of voting policies. As far back as 1909, the Arizona territory enacted a law that made speaking English a prerequisite to register to vote and run for office. The Arizona Rangers were then created to enforce this law and terrorize Latinos in the region. Today, Arizona’s Constitution still has a provision that mandates one’s ability to “read, write, speak, and understand the English language sufficiently well” in order to hold public office.

Reports of voter intimidation were common in Texas and California in the 1970s. For instance, in Uvalde County, Texas, election officials magically ran out of registration application cards when Latino applicants asked for them. And it wasn’t until 1975 that Texas translated legislative documents into Spanish. In California, an official asserted that “If the Spanish people do not speak English, they should be kicked back into Mexico and not be allowed to come back.”

And let’s not forget that, while Puerto Rican residents are U.S. citizens, they cannot vote in presidential elections. That’s more than three million Latino American citizens who do not have the right to vote.

While the Voting Rights Act of 1965 made immense progress for some communities of color, it also excluded protections for Latinos until MALDEF fought to expand the Voting Rights Act in 1975 to include language minorities. And since the Supreme Court gutted the VRA in 2013, all voters of color continue to face renewed voter suppression tactics.

As of 2016, eight million Latino voters lived in jurisdictions freed from oversight from the federal government, a direct cause of the wave of anti-voter legislation we see today in the states. So the fight continues to ensure every eligible Latino voter can cast a vote because, as of April 2021, 47 states have introduced over 350 bills aimed to restrict voting in communities of color.

Just this past July, the Supreme Court upheld Arizona’s voting laws that ban the collection of absentee ballots by anyone other than a relative or caregiver, and throws out any ballots in the wrong precinct—measures that specifically take aim at the Latino community’s access to vote in the state. Alarmingly, the Court used the false narrative of voter fraud prevention as a justification for its decision—despite no evidence of widespread election fraud nationwide. Election law experts point out that this decision may make it more challenging to strike down future measures that limit voting rights.

Despite these obstacles, for the first time in history, more than half of eligible Latinos voted in the 2020 election! More than 18.7 million of us showed up at the polls, meaning that one in ten voters was Latinx. We helped deliver critical wins. But we cannot take for granted the progress that we’ve made. We must urge Congress to pass the “John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act” and the “For The People Act,” which will restore protections of the Voting Rights Act, among other provisions to make the ballot casting process more accessible for all Americans. If we truly want this government to be for the people, by the people, and of the people, then our right to vote must be protected.