The Latino community in the time of coronavirus: Still waiting for a government response

By Emily Ruskin, Senior Immigration Policy Analyst

On July 22, UnidosUS released the white paper The Latino Community in the Time of Coronavirus: The Case for a Broad and Inclusive Government Response, which documents the disparate health and economic impacts of the pandemic on Latino communities to-date and contextualizes them within historic inequalities.

On July 30, the Department of Commerce reported the worst economic contraction in U.S. history; the following day, the economic relief measures meant to help families weather the pandemic expired. Less than two weeks after payments stopped and rent moratoria ended, there are already signs of Americans in crisis: overwhelmed food drives, looming evictions, and impending utility shutoffs. Latinos have been further squeezed by these downturns. Inevitably, with 16.3 million workers unemployed and the Senate adjourning before another relief bill could be negotiated, more people will be pushed to take unsafe work, and the virus will continue to spread.

A week after the relief measures expired, President Trump announced a set of executive directives he claims “will take care of, pretty much, this entire situation,” ‘this situation’ being the worst health and economic crises in our lifetimes. The reality is that the president’s announcements do nothing to address the pandemic—they do not expand coverage of COVID-19 testing, treatment, or vaccines, even though more than 5.2 million Americans have fallen ill, nearly 170,000 have died, and 40-50,000 more are contracting the virus every day. If the directives could be legally implemented, which is strongly contested, the measures would reduce unemployment benefits and make them difficult and expensive for the states to distribute; they would also fail to extend the eviction moratorium, help people pay rent, or put food on the table. The directives ultimately upended bipartisan talks for further congressional action and fall far short of what is needed, namely, broad and comprehensive legislation that will defeat the virus, help families meet their basic needs, and put the United States on a path to economic recovery.

As the country waits for Congress to return to Washington and pass a new stimulus bill, this blog post documents conditions in Latino communities just as previous relief measures expired; much of the data below also update figures from our recent white paper. At best, Congress will reach an agreement in September and some forms of economic relief will resume, albeit with a lag in payments few families can afford. At worst, we are on the precipice of an even larger national crisis. The current moment will be an important milestone on either trajectory.

Imbalanced COVID-19 Case and Death Rates

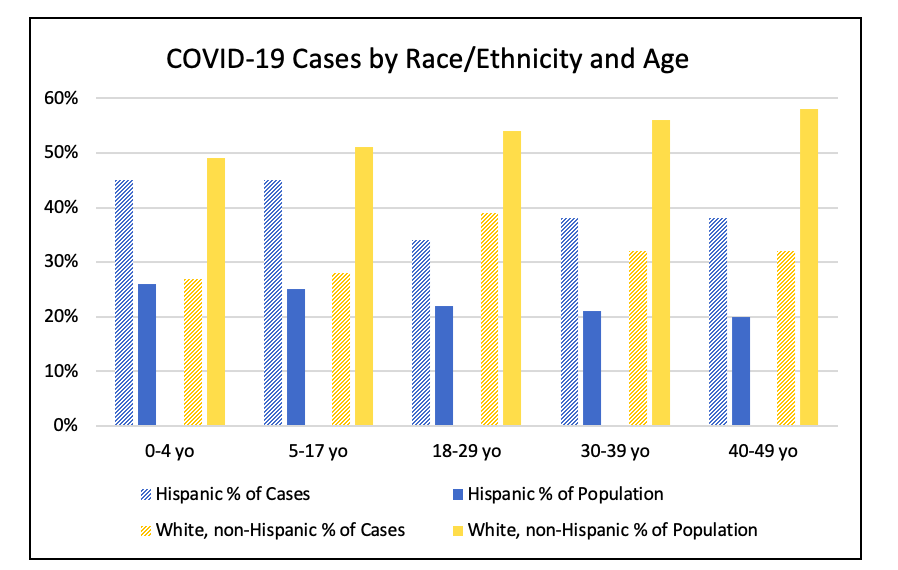

Latinos make up 18.5% of the U.S. population, but, as of August 13, make up 31% of coronavirus cases. By comparison, non-Hispanic Whites make up 55% of the U.S. population, but only 39% of cases.

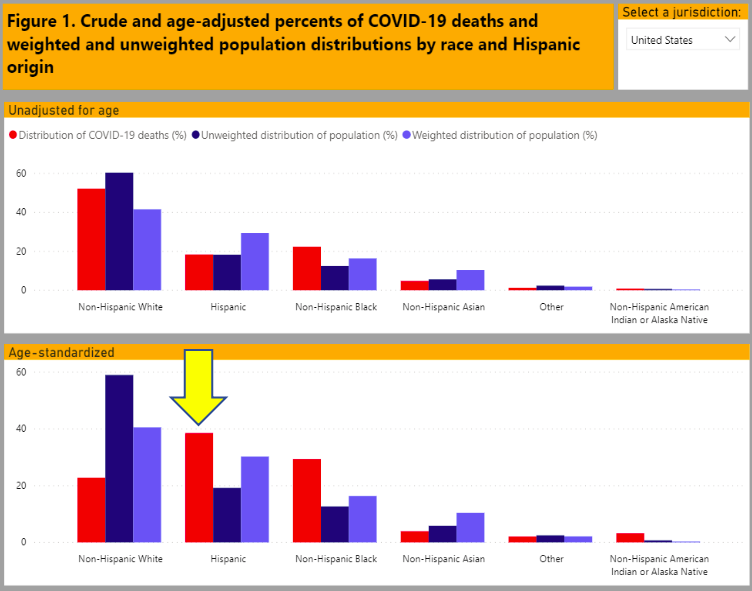

The coronavirus was initially thought to infect and kill mostly elderly patients, which is still true of non-Hispanic White patients. In Latino communities however, the virus has attacked the young and vibrant. Across age groups from 0-49, Latinos continue to get sick and die from COVID-19 at the highest rates relative to their share of the population, and in most cases, at the highest rates of all known cases and deaths in the United States.

COVID-19 has low infection rates in children in high-income countries, which should include the United States.

Yet, child cases began exploding this summer, especially in states with growing outbreaks, such as Florida, Texas, and California. These states also happen to have large Latino populations; Latino kids make up one-third to half of their child populations, respectively. The number of children testing positive for coronavirus in Florida grew more than 30% in July, when state data seemed to indicate nearly one in three children in Florida was testing positive for COVID-19. Florida’s Department of Health has since blamed a ‘computer error’ for the high rate. In northern Texas, local reporters found at least 430 infants with confirmed cases, though the Texas Department of Health was only reporting 125 cases for the state. Even in California, which was seen as managing the virus well early in the pandemic, currently has 56,000 confirmed cases in children ages 0-17: that’s equal to the total number of cases in Singapore, which was once seen as a hotspot.

While child and youth mortality rates remain low, the long-term impacts of the disease on a generation of Americans are concerning. Early research suggests the disease can cause major organ damage, neurological and psychiatric disorders, and disturbingly in children, multi-inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C). Based on similar viruses, COVID-19 is expected to cause chronic illnesses in at least a portion of recovered patients. With such a disproportionate number of young Latinos falling ill, we can expect our community will also share an outsized burden of the disease’s lasting health effects for years to come.

Disparate Economic Impacts

Since the start of the pandemic, Latinos have experienced the highest rates of unemployment and reported loss of household income, despite having the highest labor force participation rates of any racial or ethnic group. Even though the official Latino unemployment rate decreased from 18.5% in April (this was later adjusted to 16.5% by the Bureau of Labor Statistics) to 13% in July, Latino workers currently make up 22% of unemployed Americans (Latinos are only 17.5% of the total labor force).

Compounding the financial consequences of losing work, Latinos make up only 10% of unemployed workers who receive unemployment benefits (UI). UnidosUS polling in Arizona, Florida, and Texas found roughly half of out-of-work Latinos did not apply for unemployment insurance benefits (UI), primarily because they felt they wouldn’t qualify or because the process was too inaccessible. For those who do apply for UI, research suggests Latino and non-Hispanic Black applicants are approved at the lowest rates.

American families continue to go hungry as a result of the pandemic’s economic fallout. As of July 21, the most recent census data available, 21% of Latino households with kids reported not having enough to eat. Recent polling by Northwestern University suggests a larger and growing share of Latino families may be experiencing hunger due to the pandemic. In their most recent study, 47% of Latino families reported not having enough food or money to buy more—the highest rate of any racial or ethnic group polled.

As American workers lose jobs, they also continue to lose health insurance during the worst health crisis in generations. Before COVID-19, 19% of Latinos where uninsured due mostly to affordability and barriers to access. As of July 21, 22% of Latinos nationwide report having no form of health insurance. Rates are more dire in states that did not expand Medicaid, such as Texas, where 32% of Latinos report being uninsured.

Many Grains of Salt

The above figures may paint a dismal picture of disproportionate harm on Latinos and other communities of color, but it is worth noting the above analysis is based only on available data. These figures likely undercount true impacts. At the time of writing, the CDC is reporting racial and ethnic data for only 48% of COVID-19 cases and 83% of deaths. Projects like the COVID-19 Racial Data Tracker show some states, many with large Latino populations, are barely tracking race and ethnicity. In Texas, where 40% of the population is Latino, ethnicity is unknown for 93% of cases. The Trump administration’s recent change in data policy—an unprecedented memo requiring hospitals to share information directly with the White House instead of the CDC—has only worsened data quality. This is likely one of the reasons the United States has the highest number of ‘missing deaths,’ or total deaths which are higher than official counts.

It is possible that Hispanic deaths are going uncounted in part due to the high number of Latinos dying at home. The Texas Department of Health adjusted its COVID mortality rate twice in the past two weeks; both new calculations show Hispanics making up nearly half of the state’s deaths, even though only 40% of Texans are Latino. In the Houston area, two-in-three people dying at home from coronavirus are Latino, even though Latinos are only 45% of the city’s population. Similar spikes in uncounted deaths happened in New York City and around Lowell, Massachusetts. All three locations have large Latino immigrant populations. The chilling effects of the Trump administration’s public charge rules were deterring immigrants and their families from accessing health care and other necessities even before the pandemic. COVID-19 has so exacerbated this problem that on July 29, a federal judge blocked the administration from implementing the rules because they endanger immigrant lives and undermine public health efforts to control the disease.

Moreover, the administration’s attacks on immigrant communities means that current data collection, especially government survey-based data, probably do not fully represent populations with large immigrant communities, such as Latinos. Beyond public charge, the administration has unconstitutionally sought to deter immigrants from participating in the 2020 census—a large survey. When it did not succeed in adding a citizenship question meant to disenfranchise voters of color, the White House threatened to omit undocumented immigrants from the count entirely. While the related court cases continue, the desired end result is still the same: many immigrants and their families fear participating in the census may have negative consequences, including deportation. As a result, many Latino communities are wary of government data collection or surveys which might ask about immigration status.

Given all the caveats, what we know about the effects of COVID-19 on Latino and immigrant communities is tenuous at best, but even these tenuous data show American families struggling and grieving.

Recovery is going to require inclusive relief now and a concerted effort to create an equitable recovery moving forward. UnidosUS will continue working in partnership with Affiliates to call on Congress to pass an equitable relief bill now. Americans—including Latinos—cannot afford to keep waiting.

Related Research

Latinos in the Time of COVID White Paper and media call with members of Congress

UnidosUS July Latino Jobs Report

UnidosUS Poll Results: Economic Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Latinos in AZ, FL and TX

Related Advocacy

Letter from Rep. Joaquin Castro to Senators Cornyn and Cruz in support of HEROES or similarly inclusive legislation, which cites UnidosUS report findings on disparate impact on Latinos.

Letter from Representatives Soto and Murcasel-Powell to Senators Rubio and Scott in support of HEROES or similarly inclusive legislation, which cites UnidosUS report findings on disparate impact on Latinos.

UnidosUS Letter to Senate Leadership, “HEALS Act Ignores the Devastating Impacts of COVID-19 on Latinos”

Miami Herald Op-Ed including UnidosUS Affiliate Hispanic Unity Florida, “The next federal relief package must include help for immigrants”

San Francisco Examiner Op-Ed by UnidosUS Affiliate MEDA, “It’s going to get even worse for California’s Latinos unless the U.S. Senate acts swiftly around HEROES Act”

Arizona Mirror Op-Ed, “We can’t fight COVID-19, rebuild the economy if we leave immigrant communities behind”