Latinidad: Navigating the labyrinth of Latinx identity

Noel Quiñones says identity is like a labyrinth you spend your whole life navigating. There are endless turns and dead ends, but there are invaluable lessons to learn along the way.

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

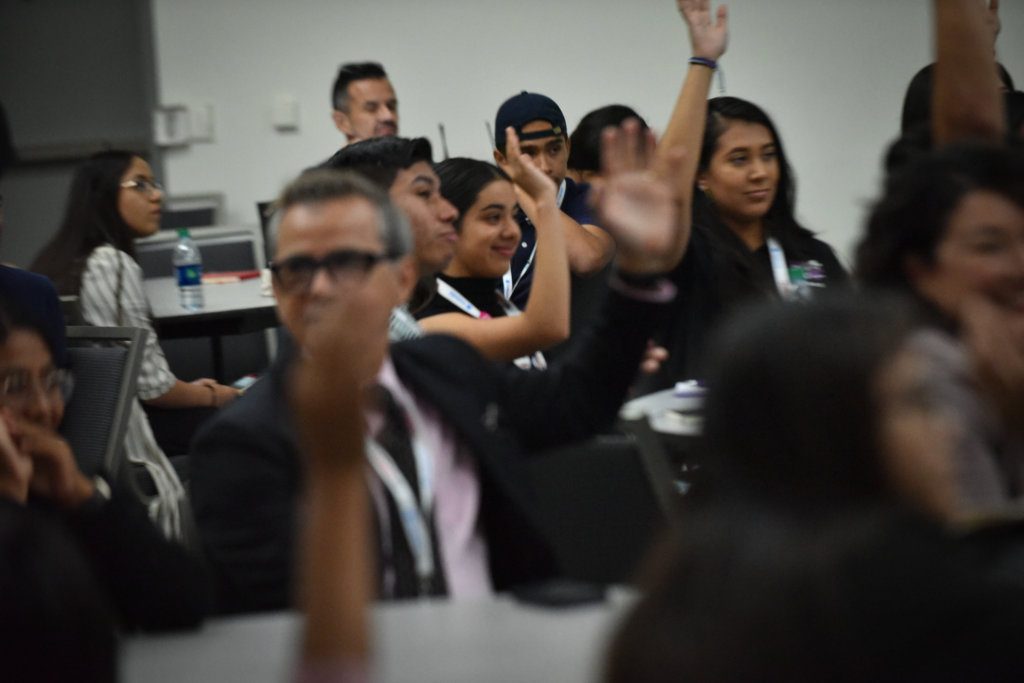

Quiñones was one of three young people onstage at the 2018 UnidosUS Annual Conference talking about latinidad and what it means to be Latinx in 2018.

As moderator Brenda Gonzalez, UnidosUS California Regional Director, said, it’s important to have these conversations now, after “so much of the Latinx identity has been defined without us.” As organizers, writers, and performers, the panelists approached navigating the labyrinth of identity in different ways, but they each prioritized storytelling and touched on similar themes.

COLONIZATION OF THE INDIGENOUS

The three speakers agreed that so much of Latinx identity is tied to the tension between staying true to cultural roots, while acknowledging that much of what you know is the result of colonization.

Growing up in Catholic school with a religious mother, trans activist and organizer Adriano Perez had a firm grasp of what was expected of their assigned gender. If their ancestors hadn’t been colonized by Christians, those strict roles might not have been enforced.

“Gender roles like this didn’t exist indigenously,” Perez said.

“If we weren’t colonized by Catholicism, I would have been a leader. Trans people were respected as leaders to indigenous people.”

Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodriguez, the founder and owner of Latina Rebels, discussed storytelling as a prominent method of education that isn’t valued in traditional academia. “Stories have always been the way I learn,” she said.

“And as part of an indigenous culture, we get a lot of our knowledge through stories.”

As those stories are passed down, later generations can build upon the wisdom of the previous, benefiting from all the sacrifices made to get them there. “I am my mommy’s revolution,” Rodriguez said. “I get to do things she never dreamed of.”

amazing crowd td at @WeAreUnidosUS pic.twitter.com/wTj5887tqb

— Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodriguez (@priscadorcas) July 7, 2018

Quiñones, who identifies as Afrolatino, feels that race relations in the United States fall into a binary of Black and White, which ends up hurting everybody. “I don’t live up to the monolith of being Black in America,” he said.

“Latinidad is a labyrinth. A beautiful labyrinth. We try to hold on to our traditions but also be American. There are black Latinos and there are white Latinos. It’s not either or. It’s a conversation.” – @noelpquinones discussing the power of Latinidad identity. #UnidosUs18

— Latino Memphis (@LatinoMemphis) July 7, 2018

Keeping the dynamic between Black and White ends up erasing the experiences of people from every other group, since many people don’t fit the conventions of “whiteness” or “blackness” no matter how they identify. “That’s where latinidad confuses everybody,” Quiñones said.

“We’re trying to acknowledge and hold onto our history and past while also assimilating into America.”

AN IN-BETWEEN LIFE

The tension of existing between two extreme poles, of being seen “this” or “that” way, was a recurring theme in the session.

When Rodriquez was in grad school, a professor told her to visit the writing center after receiving a D on a paper. The writing center said her English wasn’t “good enough” to see a tutor, and that she needed to visit the center for international students. When she got there, she was told her English was “too good” to be considered international.

Perez grew up in a mixed-status family in a border town in Texas. “It was always on my mind,” they said.

“Growing up I could see Mexico from my window.”

Being the only U.S. citizen in the family came with the pressure of “carrying my family’s hopes and dreams with me.”

Quiñones had trouble claiming a Latinx identity until he first heard the term “Afrolatino” when he was 20. “I had no language for my loneliness,” he said. When he first heard bomba—a style of Puerto Rican music that combines Spanish and African traditions—he cried. “It was like tombstones breaking in my stomach and my ancestors speaking through me,” he said.

LOOKING FOR ACCEPTANCE

Whether from within, from family, or from society, each speaker has sought to break free from what is expected of them and embrace who they really are.

Rodriquez used to try everything possible to conform to strict American beauty standards. “I bought a pair of turquoise contacts from a girl at lunch who had a bag full of them,” she said. “They cost $20. Self-hatred is profitable.”

It took time, but she realized that she can exist and thrive outside of Euro-centric expectations of beauty. “Nothing is wrong with me; something is wrong with the system,” she said.

“For years I hated being Latino because I didn’t get what it meant,” Quiñones said.

“We have to move forward with another understanding of latinidad. It’s a labyrinth and it’s a conversation.”

Perez said acceptance came in several forms, including coming to terms with their trans identity, and an uneasy relationship with their mother. After coming out, their mother kicked them out of the house, and they haven’t spoken since. “Because of everything happening in immigration right now, I don’t even know where she is,” they said.

Breaking free and determining their own identity was a common theme through the experiences of the three speakers and being part of a minority group has shown them the flexibility of things after realizing these categories don’t have to be so defined. “You even find a way to make your own family,” Perez said.

RELATED CONTENT