Immigration by the Numbers: USCIS Reaches a Significant Milestone in Reducing its Immigration Backlogs

Immigration by the Numbers is a series of timely, data-driven analyses of key immigration issues facing the Latino community and U.S. policymakers.

By Cristobal Ramón, Viktor Olah, Laura Vazquez, and Gary Sang

Last month, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) released their Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 data, showing a reduction in net-backlogged applications[1] for the first time in over a decade. The backlog decreased by 15 percent as digitalization and bureaucratic improvements allowed the agency to process 10 million applications during FY 2023.

USCIS accomplished this by using appropriations dedicated to reducing the backlog to hire more staff and digitize its forms to make it easier to complete applications. While this accomplishment is a major milestone for the agency, additional federal funding is still needed to maintain and build on these gains.

The Factors Generating the Backlog in the Legal Immigration System

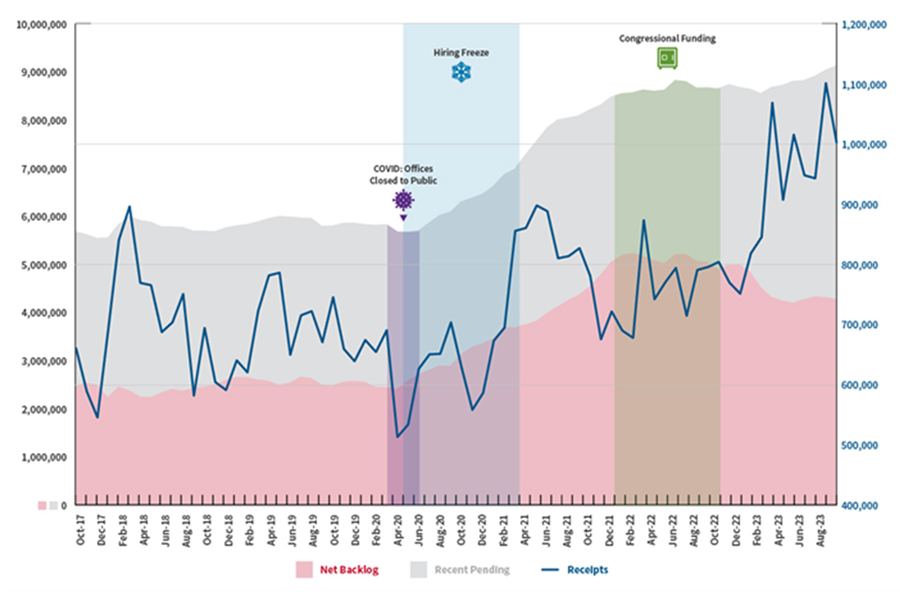

The backlog has been a significant challenge for the U.S. legal migration system in the last decade. As Figure 1 shows, the backlog steadily increased from 2.4 million in October 2017 to 4.2 million by August 2023. This backlog includes affirmative asylum applications (763,400), family-based petitions (714,800), adjustment of status for green cards (539,800), and employment authorizations (387,700). In total, USCIS has 9 million backlogged applications, including 4 million backlogged applications in the USCIS system.[1]

Source: USCIS

One major factor generating this backlog revolves around the agency’s inability to secure enough funding to hire more Immigration Officers[3] [4], a problem that grew more acute in 2020. In February 2017, [5] [6] the Trump administration required more in-person interviews for green card applicants on national security grounds, making the process more rigorous for these individuals.

This measure contributed to the cancellation of 280,000 interviews for immigration benefits after USCIS stopped in-person services between March and August 2020 due to concerns about the pandemic. Without a robust library of digitized forms, the agency could not process applications remotely to offset the decline in revenues stemming from canceled interviews and the lower numbers of individuals seeking to migrate to the United States during the pandemic (Figure 1).

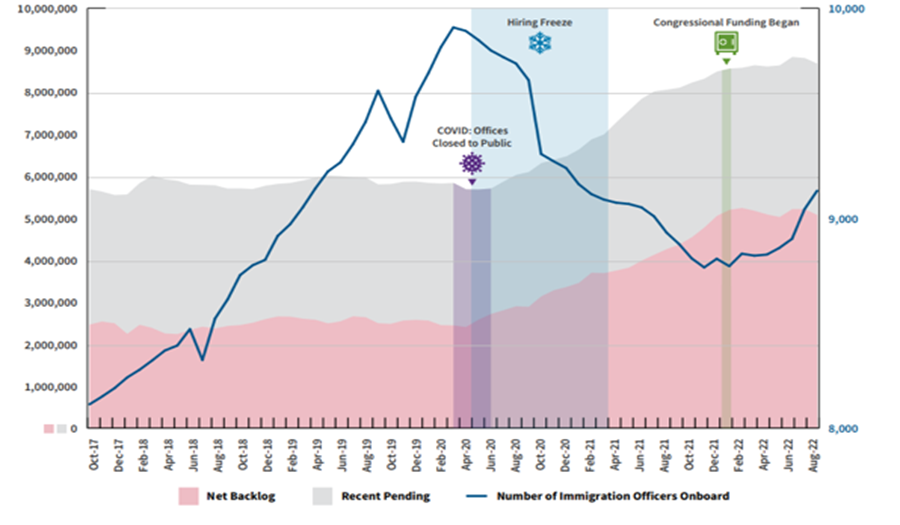

This decision impacted staff levels after USCIS implemented a hiring freeze in the summer of 2020 in response to the decrease in fee receipts from immigration applications. As Figure 2 shows, the number of Immigration Officers [7] dropped from 9,800 [8] [9] in March 2020 to 8,800 in November 2021 since the agency could not replace the individuals who left the agency during this time.

Source: USCIS

The agency’s reliance on paper-based forms also contributed to the backlog. Although USCIS has released 17 online forms, individuals must complete physical forms for most immigration applications. The growing length of USCIS applications[2] [10] [11] and the lack of resources to publish more forms online has undermined digitization efforts, increasing the average processing times from less than four months in 2012 to over a year by 2022.

USCIS’ Reduction of the Backlog in the Legal Immigration System

In the wake of these problems, USCIS has taken three sets of measures to reduce the backlog. In addition to offering more online applications, the agency has improved its website. Applicants can change their address and make appointments online, tasks that previously required phone calls, and in-person visits with significant wait times.

The agency also addressed “backlogs in backlogs” — namely, the growing backlog for work permits that certain individuals can access while their main application remains in the USCIS backlog — by temporarily extending the validity of particular work permits from two to five years and allowing more online interviews.

Finally, Congress appropriated[12] [13] [14] [15] $275 million to support USCIS. While less than originally requested, it has allowed them to hire 200 staff members for their asylum division to address the influx of asylum applications coming from arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border.

USCIS also announced a new fee schedule[16] [17] in January 2024 and expanded premium processing for select applications in June 2023, which will support operational costs and the expansion of its workforce to build on the gains made in recent years.

These steps have significantly impacted the existing backlog. By the end of FY 2023, the USCIS backlog decreased from 5 million applications in FY 2022 to 4.3 million applications, marking a 15 percent decrease. This progress occurred even though the agency received a record 10.9 million filings during FY 2023, compared with a more typical level of 9 million receipts in FY 2022 and FY 2021.

USCIS Requires Additional Attention from Lawmakers to Build on the Backlog Reduction

Despite the impact of the pandemic on immigration benefits processing[18], Congress and the agency have improved the experience of non-citizens in the United States, including members of the Latino community. This progress demonstrates that Congress can improve the U.S. legal immigration system by providing USCIS with the necessary resources to fulfill its mission. The measures USCIS adopted to address its backlogs can help other agencies that process immigration applications, such as the Department of Justice’s immigration court system, to address their own backlogs[19] [20].

Additional steps are needed to continue making progress. USCIS needs to expand its digital capabilities so more individuals can apply for immigration benefits online, improving the agency’s efficiency. Congress also needs to continue funding the agency to hire staff to continue processing the backlog and new applications. Finally, to assist with hiring, the executive branch should consider waiving rules that bar retired employees from returning to federal service while receiving their pension.

[1] USCIS uses the term net backlogs to describe the load of applications that have exceeded the agency’s target goal wait times for applicants. This blogpost will use the term “backlogs” to describe these applications.

[2] USCIS added a total of 508 pages to its immigration forms from 2003 to 2022. It added 81 pages from 2003 to 2008, 213 pages between 2008 and 2016, and 214 pages between 2016 and 2022.