ProgressReport.co Worked with UnidosUS’s New ‘Voices’ Page to Profile Six Diverse Latinos for Hispanic Heritage Month. Here’s Part I.

Hispanic Heritage Month, which runs from September 15 to October 15, is a key time to consider what makes a person Latino, which, given the long history of migration to the Americas and the interaction with the Indigenous people who already lived there, can mean many things. UnidosUS has created a new website called Voices to understand and explore that identity, and since ProgressReport.co provides educational resources around that same subject, we decided to extrapolate. The following is a collection of the first three Latinx people who lent their voices to explain what makes them Hispanic or Latinx in their own unique way.

Magdaleno Rose-Avila

Civil Rights Activist, Age 76

Atlanta, Georgia

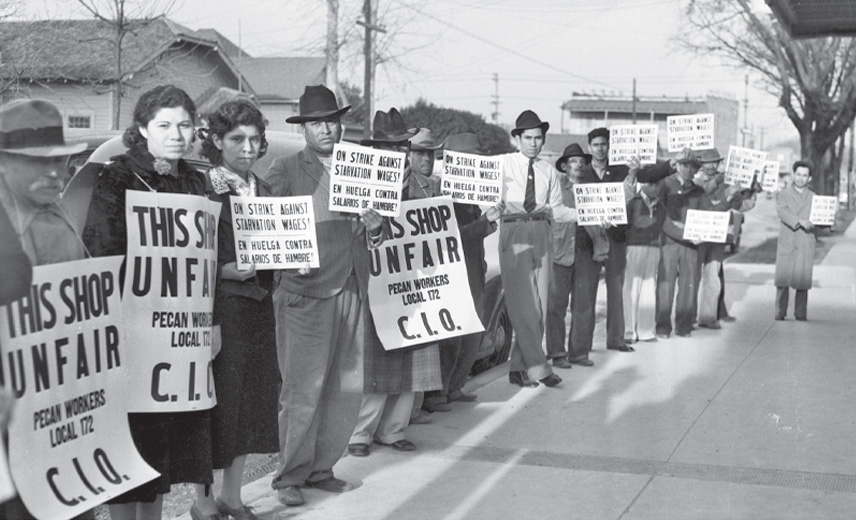

Born into a Chicano family in Colorado in 1945, Rose-Avila spent his early childhood working in agriculture, and getting into some trouble, but not always “good trouble,” like the kind late Civil Rights Movement Leader John Lewis spoke of. He began studying at University of Colorado about the time that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and he began to see the need to use his voice on behalf of King and civil rights. Soon, he was getting into good trouble, picking up the banner to fight for better representation of Chicanos.

He went on to work for the United Farm Workers Union (UFW) as an organizer, then later became the founding director of the César Chavez Foundation and the leader of the anti-death penalty campaign for Amnesty International. In the 1990s, he founded Homies Unidos, the first-ever rehabilitation program for gang-involved migrant youth deported to their native El Salvador at the end of that country’s 12-year civil war. More recently, he has worked on immigrant rights in cities such as Seattle, Los Angeles, and Atlanta, and as a leader for Witness to Innocence, a collective of people who were exonerated from death row and are working to ensure anyone who has been condemned to the death penalty, the majority of whom are people of color, have received a fair trial.

An avid writer and poet, Rose-Avila is a strong believer in using inclusive history to heal generations of trauma in underserved communities and in those communities that have historically had the power. He currently writes for Latino newspapers in Philadelphia, and Chicago.

“One of the problems we have in America is that they don’t write about our history, they don’t honor it, they don’t give us the space that we need, and as long as our children are not learning about the contributions we have made to the culture, the food, the growth of America, we will not be recognized,” Rose-Avila said in his Hispanic Heritage Month video commentary.

He stands with UnidosUS in hailing the passing of California’s AB 101 requiring all students to take an ethnic studies course before graduating high school, and in calling out policymakers in states like Arizona and Texas who have sought to suppress the teaching of ethnic studies to maintain the status quo.

These are debates he’s witnessed throughout his life and career as an activist.

“One of the problems we have in America is that they don’t write about our history, they don’t honor it, they don’t give us the space that we need, and as long as our children are not learning about the contributions we have made to the culture, the food, the growth of America, we will not be recognized,” Rose-Avila said in his Hispanic Heritage Month video commentary.

He stands with UnidosUS in hailing the passing of California’s AB 101 requiring all students to take an ethnic studies course before graduating high school, and in calling out policymakers in states like Arizona and Texas who have sought to suppress the teaching of ethnic studies to maintain the status quo.

He also suggests that students and educators talk to their elders and record their stories.

“The great stories are within our mothers, fathers, our abuelitos and abuelitas, our tíos, our tías,” he said in his video. “They have the real history, and those of us need to capture them.”

Cristina Ruíz

University of Notre Dame Anthropology Student, Age 21

Los Angeles, California

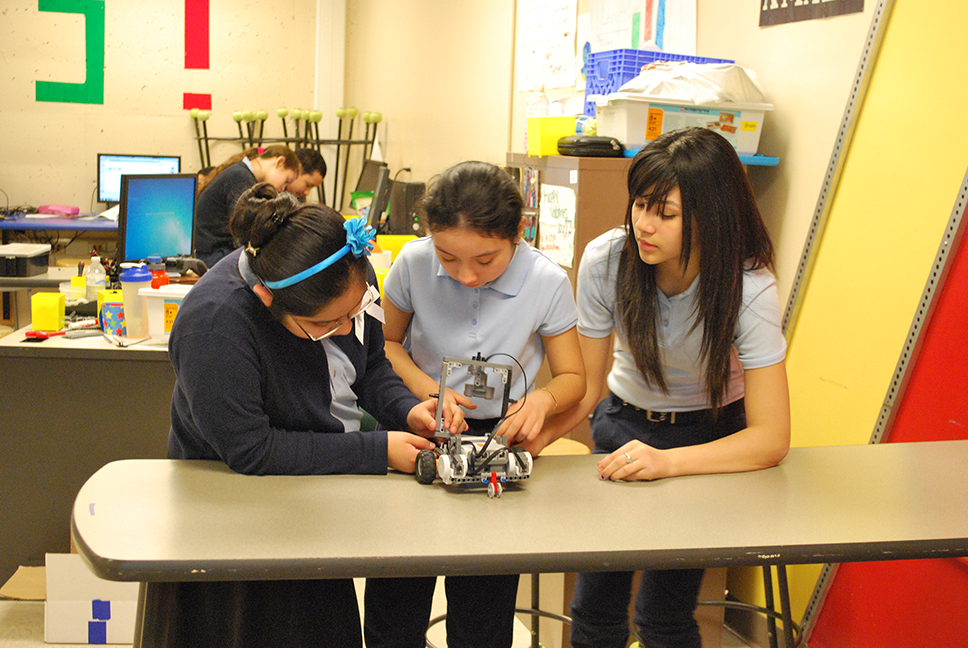

University of Notre Dame anthropology and sociology major Cristina Ruiz came to UnidosUS this past summer as an education intern with a passion for exploring intersectional identity, like her own Chinese and Mexican American background.

“I was essentially studying myself,” she wrote in a mini ethnography she developed featuring interviews with a wide array of Asian Latinx students and researchers. Several other participants had Chinese and Latin American roots like Ruiz, and she spoke colorfully about the fusion of food in their homes, but also of the struggle to explain one’s identity to those who don’t know how prevalent Asian migration to Latin America has been throughout history.

She also explored the unique identities of two Filipino scholars who might not necessarily call themselves Latino but who certainly feel a sense of cultural and linguistic kindship to that community. After all, the Philippines was a Spanish, Catholic colony, and that’s notable in the religion and some of the vocabulary of its people. Plus, Filipino immigrants have often settled in or around Latino neighborhoods and vice versa.

That understanding of self and its relationship to her Asian Latinx community, to the broader Latinx community, and the whole of American society continues to grow. In fact, her short Hispanic Heritage Month video for the UnidosUS Voices page highlights in just one minute how her perspectives have evolved.

“As someone who is Mexican and Chinese, I’ve often had to juggle these two identities and had to question myself on what does it really mean to be Mexican? What does it mean when I can’t speak Spanish? What does it mean if I’m not fully Mexican?” she asked in her video. But through these various ethnographic studies and projects, she’s coming to peace with those questions and turning them into a source of pride.

“Now, at this point in my life, I realize that these questions don’t really matter. My identities don’t have to contradict each other. In fact, they can go in tandem. To me, being Chinese and Mexican, I can be anything I want. These cultures are what make me—me.”

Irina Borló Rodriguez

Miami Dade Public Schools Special Education Teacher, Age 45

Miami, Florida

Irina Borló was born to Afro-Cuban parents in Cuba, a country that is more than 50% Black. Her mother was a microbiologist and her father a mechanical engineer in the Cuban Navy, professions that might not have been possible for Black people on the island if not for the desegregation that the 1959 Revolution first attempted to address.

But by the time Irina was a young college graduate in the 1990s with a degree in foreign languages, Cuba was a place of many struggles. The Revolution, which had relied so heavily on support from the Soviet Union, struggled to support itself economically when the Eastern Bloc fell. The U.S. embargo made it hard to get supplies of all kinds, and as tensions rose, so did the sense of disillusionment with a government that seemed to be fighting for a communist system that wasn’t working.

Like many young Cubans in that time, Irina wanted out. In the mid-1990s, many Cubans took the Strait of Florida in rafts, but still others sought other avenues of defection. Borló’s moment came a few years later in 1999, when a friend in Bolivia gave her a letter of invitation to come on an exchange there—a chance to teach English.

“The idea was to stay abroad from the beginning,” she told ProgressReport.co. Then in 2003, she had an opportunity to teach in an even stronger market—Santiago de Chile. There she met and married a Chilean man, and in 2007, they had their first child Santiago, and a second son Omar in 2008.

By 2015, big changes started happening on the island. The Obama administration had taken its first steps to normalize U.S.-Cuba relations after a five-decade freeze, and Irina’s husband, a businessman, recognized an opportunity for international investment. She agreed to go back to Cuba with him to explore the possibilities, but while there, the two decided to split up.

“It was hard to go back to Chile and start from almost zero because we had sold the house, and in Cuba we lost a lot of money, so the best option was coming to the States,” she said. Her husband took the children back to Chile while Borló got settled in the United States.

“There were misunderstandings, tears, and judgements, but I never lost hope and faith,” she said.”

By 2017, Borló and her ex-husband agreed to let the children emigrate to Miami to be with her, and that’s where the three of them have been ever since. Often called the “Capital of Latin America,” Miami makes for an interesting place to instill in her children a strong sense of Cuban, Chilean, and multicultural American identity.

“What does it mean to be Latino? It means to have all to have all of your ancestors, whether they’re Black, or white, or Asian, or Aztec or Mayans or Taínos in one vase,” she says, referring to the Spanish word for a glass or cup. ”You shake it, and it results in a very rich culture with delicious food,” she said in her Voices video.

“We have rice and beans, tostones, tacos. And then also you have good music. You have music from Spain and from Africa, that you also mix and you get what we know as boleros, cumbia, salsa, tango, that means being Latino.”

While she never practiced the Afro-Cuban religion of Santería, she does familiarize her children with the various deities and the ways they show up in Caribbean culture, especially through music and dance. She plays them music from the island as well as from South America, and she jokes that while none of them are very good dancers, the dancing got them through quarantine. It also helped the children to discover they have an ear for music, and in fact one of them has become a guitarist.

Her skills as a teacher, especially a bilingual one, have come in handy in the diverse Miami Dade public school system where she works as a special education teacher.

“As an immigrant involved in special education, I can see that the government invests a lot of resources in making these students succeed in school and life. I find it remarkable,” she said. “I find it valuable that it is also constitutional for children to be provided proper education, regardless of their migration status, background, and cognitive skills.”

But she doesn’t take those laws for granted, and appreciates the opportunity to show other students, parents, staff, and teachers that they have to fight to defend their rights for equal access to education. It’s an ongoing process, one that has to be continually adapted to changing times and new educational discoveries.

“That’s the hardest part,” she said.

Check out all the videos of these Latinx contributors and more at the UnidosUS Voices page.

–Author Julienne Gage is an UnidosUS senior web content manager and the managing editor of ProgressReport.co.