Reflections on Independence:

An Interview with Paul Ortiz,

Author of An African American and Latinx History of the United States

On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass delivered an Independence Day address in which he told his audience, “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.” The year’s tumultuous pandemic paired with masses of protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement has had many Americans rethinking the 2020 Fourth of July, commemoration. Why should we congregate? Should we congregate? What risks do we take if we do? How can we talk about independence when all Americans weren’t free on July 4, 1776. How can we celebrate freedom when issues like racial profiling, police brutality, mass incarceration, and structural racism still disproportionately affect people of color?

On the street and online, Americans of all generations and ethnic backgrounds are expressing concern for these issues. At the same time, we contemplate which historic American symbols should be erased or toppled in the name of decolonization. More and more, Americans of all backgrounds are seeking out educational resources that can help them gain a more inclusive and well-rounded understanding of American history.

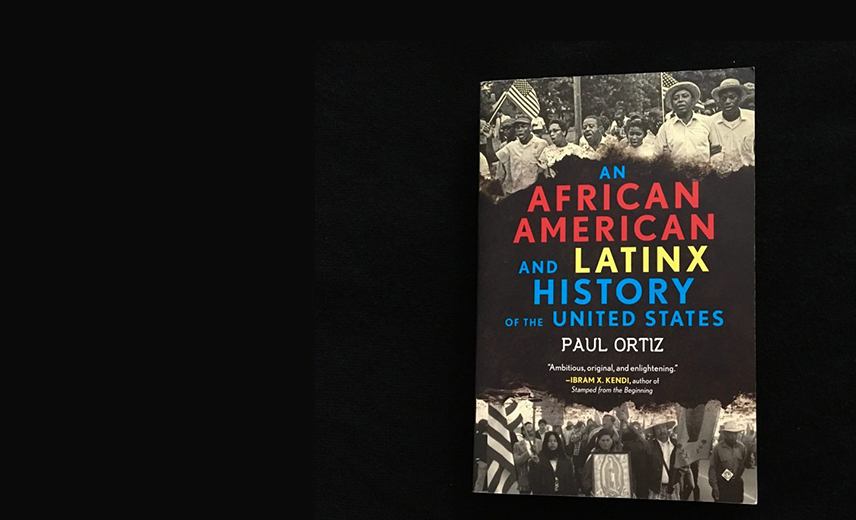

One of those popular resources is the 2018 book An African American and Latinx History of the United States by Dr. Paul Ortiz, a history professor at the University of Florida.

“I wrote this book because as a scholar I want to ensure that no Latinx or Black children ever again have to be ashamed of who they are and of where they come from,” Ortiz writes in the book’s introduction.

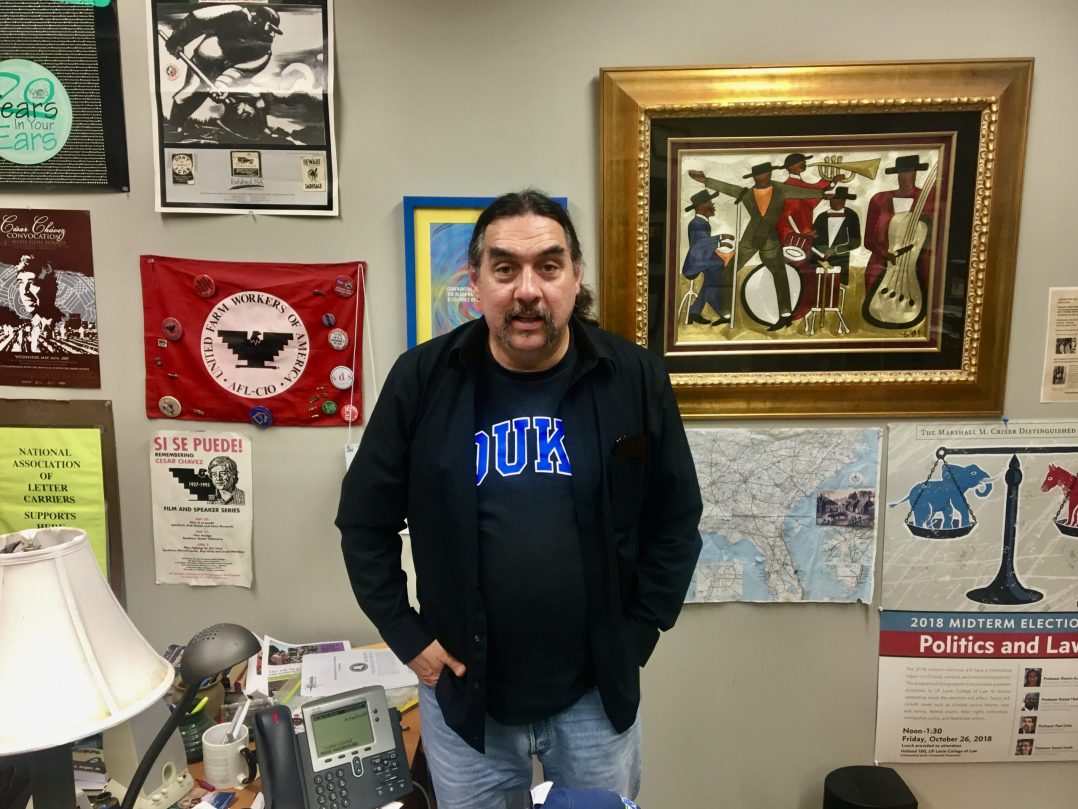

In early February, ProgressReport.co had a chance to meet with Ortiz in person and talk more about the book’s mission.

Ortiz says this generation of young people are rightly upset about the way racism continues to linger in 2020, but he’s also quick to note that freedom fighters and solidarity movements have existed since before this land became known as the United States of America.

“In order to learn how we get out of the mess we’re in, we have to learn the contemporary context for which movement organizing is taking place,” Ortiz tells ProgressReport.co.

Ortiz’s inspiration for the book is rooted in his own Gen-X awakening to the issues that didn’t get resolved during the Civil Rights Movement. Born in the 1960s, his father was a Mexican American military official whose job it was to research discrimination in the ranks. He was raised in the 1970s between Washington and California, two Western states that often pride themselves on being more progressive than the rest of the union.

At the time, it was common rhetoric for educators to tell students that racism was mostly a Southern problem. He recalls, however, White students asking him to take their side in a fight when a non-White man was dating a White woman. He recoils at the memories of watching the police beat up a Native American in the streets of Seattle. And in as a resident of Oakland, he learned about how mortgage brokers were fanning the flames of racial intolerance in an effort to raise housing prices in neighborhoods perceived to be mostly White. In his 20s, Ortiz followed in his father’s patriotic footsteps by joining the military. While in uniform, he found himself training soldiers in Panama in weaponry. At the same time, protests were erupting stateside concerning the United States’ role in fueling civil conflicts across Central America under the guise of squelching Communism.

Conflicted by his role, he came home feeling deeply disturbed by his time in military service. Soon after, a fellow veteran handed him a copy of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States.

“He said, ‘Son, you’ve got to read this book. You’re angry,’ and you know, I was really pissed off and mentally not in good shape,” Ortiz recalls. That book reflected the angst and conflict that he had long experienced. It turned out to be a catalyst. Not long after, he became a labor organizer in an attempt to level the playing field. It led him to delve deeper into the parts of American history never taught in school. He soon discovered why they weren’t.

“When you’re up against power like that a lot of things become clear,” he says.

Of course, the learning process both angered and excited him. He discovered what he wants today’s generation to know: that social justice organizing and inter-ethnic solidarity was a thing long before TikTok, the Internet, and even long-distance phone service and telegrams. In fact, such movements were often inspired from people facing similar struggles beyond the U.S. border.

Powerfully placed, the book’s first two chapters of the book feature the revolutions that led to independence in Haiti in 1804 and Mexico in 1821. Haiti was the first place in the world where enslaved Blacks successfully revolted and kicked out their colonizers, a feat that scared the living daylights out of White politicians endorsing slavery in the United States. In fact, Ortiz notes that the ruling classes of the United States, France, and Great Britain viewed Haiti as a “contagion of liberty.”

Mexico instituted and benefitted from the labor of enslaved Africans from as early as the 16th century. Then, in an about face, the country aided in helping enslaved African-Americans to reach freedom across the US-Mexican border. Mexico also developed one of the most inclusive constitutions of early democratic nations. It covered equal rights for people of all races—Black, White, Indigenous, Mestizo—of women and workers.

Well-known Black abolitionists in the United States including Henry Highland Garnet and Frederick Douglass studied this history closely. They were also keenly aware of Cuba’s struggle for independence from Spain and then, in short shrift, from the United States. Located just 90 miles off the U.S Coast, Black liberationists in the United States understood that their struggle crossed geographical lines. They hailed the efforts of Cuban freedom fighters including Black General Antonio Maceó. They knew imperialism could create an excuse to re-enslave people who’d just gained their freedom during the U.S. Civil War and the subsequent signing of the 13th Amendment to U.S. Constitution.

“You may think you’re free, but as long as you have slavery right next door and you’re not even sure slavery has quite ended in the United States, so you’re right to question this country’s commitment to ending slavery,” explains Oritz.

He notes that Garnet, who was born in Maryland, spoke Spanish because he had worked as a cabin boy on ships that docked in Cuba. He saw how terribly the Spaniards treated enslaved people there, and that fueled his inter-continental solidarity even more. And Ortiz says Cuban freedom fighters like Jose Martí, who is believed to have had both Spanish and African ancestry, were equally as inspired by characters like Garnet.

The greatest eulogy I’ve read in my entire life was one Jose Martí wrote when Garnet passed away,” says Ortiz. “I remember reading it and thinking, oh my God, you have the greatest writer of the Cuban diaspora paying homage to a Black minister and it’s just a beautiful, powerful eulogy.”

Throughout these same historical timelines, Ortiz points to times when other ethnic groups such as Indigenous people in Florida’s Seminole War fought to protect their region from slavery, and the ways progressive Whites, many of them people of faith, aided in the Underground Railroad, set up schools for emancipated Blacks, and also pushed for policy change through the Civil War and lobbying efforts in Washington.

He also notes that some of America’s most remote communities, such as Key West, Florida, have had long history of promoting tolerance. That island was celebrating LGBTQ pride and inter-racial marriage decades before the Civil Rights Movement pushed forward federal laws to prohibit segregation and discrimination.

As time went on, these liberation struggles became part of a broader effort to advance the worker’s movements, which led to the creation of largely Latino organizations such as the United Farm Workers, just as Black Americans were spearheading the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout all of these eras, Ortiz discusses the ways progressive people came together to educate each other. That included the teaching of literacy—often a prerequisite for voting—as well as tools for community organizing and resistance.

He highlights the work of the Rainbow Coalition which brought together diverse groups such as the Black Panthers, the Young Lords (a Puerto Rican group), and the Young Patriots (a working class White group) to fight for fair housing in the 1960s, or how tens of thousands or workers of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds came together in 2006 to participate in a massive May Day strike known as the Great American Boycott or the Day Without an Immigrant.

“The Latinx-led labor insurrections of 2006 provided the first hint of the beginning of a sea of change in American politics,” writes Ortiz, whose final chapter looks at how this change led to the 2008 and 2012 elections of President Barack Obama.

“Despite the claims of some in the corporate media that Latinx people would ‘never vote for a Black man,’ Black and Latinx support was crucial in Obama’s victory in key states, including Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, and Florida,” Ortiz writes.

But Ortiz is well aware that a Black president did not lead to a post-racial society. In fact, he tells ProgressReport.co he’s very concerned young people in the Trump era are having an especially hard time “questioning the parameters of their society,” but he says, in spite of this heightened climate of fear, he’s proud of the way they’re speaking out all over the place.”

He’s also proud of the way publishers and educators are helping them do so by using books like his to build out more inclusive student curricula. For example, Penguin-Random House has created a teacher’s guide to his African-American and Latinx Guide to American History. Across the country, Ortiz is being asked to help school districts revamp their high school civics and social studies classes. He says he’s inspired and even astonished by the way they’ve extrapolated from his 276-page book.

“I began by saying that African Americans did not believe that emancipation in one country was going to solve the problem,” he tells ProgressReport.co as he stands up from a desk full of historical books and papers to check on a line of college students waiting outside his office door in search of mentorship. “I found that to be one of the most remarkable case studies. It’s saying if you’re my neighbor and I say I’m free, but you’re not free, then how free am I really?”

This story was edited by UnidosUS Consultant Alicia G. Edwards, a Miami-based educator and documentarian.